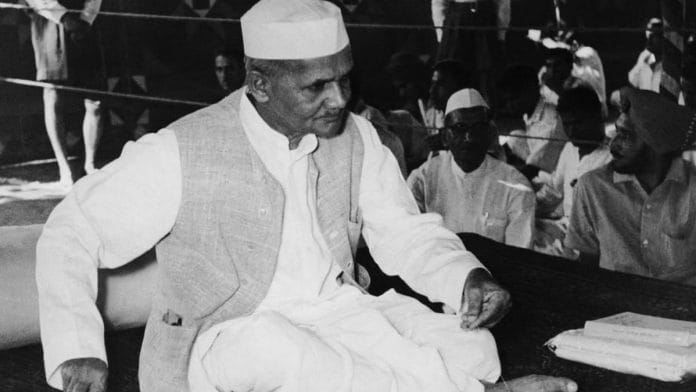

My first column in 2023 is a tribute to India’s second Prime Minister, Lal Bahadur Shastri, whose 57th death anniversary falls on 11 January. Even though his name is the bellwether of the institution where I trained for two years—from 1985 to 1987—and served for nearly nine years, first as deputy director from 1994-2001 and then as director from 2019-2021, the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration in Uttarakhand, his name does not figure in Ramachandra Guha’s Makers of Modern India. V. Krishna Ananth’s India Since Independence gives him eight paragraphs, while Meghnad Desai’s Rediscovery of India gives him three pages. In the memoirs and autobiographies of Shastri’s political contemporaries, only S. Nijalingappa, Independence activist and former chief minister of Karnataka, holds him in high esteem. Morarji Desai and Vijayalakshmi Pandit, though, were not too charitable.

Except for Kuldip Nayyar, who devoted three chapters on Shastri in his books Between the Lines and Beyond the Lines, giving a fair and candid assessment of his life and politics, most other English language journalists in India and abroad always regarded him as a shadow of his former mentor Jawaharlal Nehru, who had a 17-year tenure as prime minister. The editors of Mainstream and Seminar—Nikhil Chakravarty and Romesh Thapar were too enamoured by Nehru to give Shastri an agency of his own.

The civil servants he worked with at close quarters, L.P. Singh, C.P. Srivastava and Rajeshwar Prasad, have written their recollections of the man and his frank and forthright style of functioning, but that’s about it. Three years ago, author Sandeep Shastri (not a relation) wrote a slim volume called Lal Bahadur Shastri: Politics and Beyond. This is in contrast to the hundreds of books written on Nehru and Indira Gandhi – not just because they had longer tenures in office but also because it was part of a conscious effort to build the myth and mystique of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty. Compared to the Teen Murti Bhawan and the Indira Gandhi Memorial, where foreign dignitaries often marked their presence, visits to LBS Memorial were few and far between. In fact, when I went there in 2019 after taking over as the Director of the LBS National Academy, I was the first—and perhaps the only—visitor that day.

Also read:

An eloquent silence

Unlike his immediate predecessor, Shastri was a man of few words, his tenure quite short—just about 18 months. His correspondence was not as extensive, and his speeches—both in Parliament as well as on public occasions—were sharp, precise and to the point. He was not known to meander and often used silence as a language to communicate. His silence, which some misunderstood as a willingness to acquiesce, was both a strength and a weakness.

However, he is strongly etched in public memory as the first Indian prime minister who directed the Army to cross the border and advance forces toward Lahore during the 1965 war between India and Pakistan. And this is how the trajectory of war changed, for this was the sector where the advancing Indian troops moved right up to the Ravi river , close enough to threaten the capital of Pakistan Punjab.

It is true that Lahore was the capital of the Sikh empire, but as per the 1808 Anglo-Sikh Treaty of Amritsar, Maharaja Ranjit Singh had to accept two conditions. The first condition barred him from extending his eastern boundary beyond the Sutlej river, while the second condition forced him to cancel support for the Marathas. The positive fallout of this treaty was that his Generals marched ahead of the Kashmir valley to take possession of Gilgit, Baltistan, Ladakh and key territories in Tibet, including the much-contested Aksai Chin region in 1842.

Also read: 6 borders, 1 LoC, 4 forces—Challenges of guarding India in face of suicides, fratricides

Victory after 1962

In 1962, the territorial contest with China led to India’s humiliating capitulation at the hands of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in the North-East Frontier Agency or NEFA (as Arunachal Pradesh was then called). By 1965, the Generals in Pakistan were under the impression that they could ‘walk over’ into Kashmir, much as the PLA had done three years earlier. However, this time, the decision-making was sharper and clearer. Shastri took the bold decision to open the Punjab frontier, upsetting Pakistan’s calculations that engagements would be limited to Kashmir and the Rann of Kutch.

He thus reversed the humiliation of the 1962 war with China when the PLA overran the entire NEFA. While it is true that both India and Pakistan had to withdraw their troops to their respective positions, the point was well established: The Indian Army was no walkover, and that if its soldiers got the support of the political leadership, they were second to none in terms of valour. Shastri had a very competent defence minister in Yashwantrao Chavan, who, unlike his predecessor V.K. Krishna Menon, had his ear to the ground, and a connection with soldiers on the frontier. He gave his Generals and field commanders the freedom to strategise for war.

Also read:

Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan

What galvanised the nation was his slogan of Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan (Hail to the soldier, Hail to the farmer). Through this, he credited the farmers for contributing not just to food security but also to national security, for the bulk of soldiers came from the peasantry. To him goes the credit for establishing the Border Security Force (BSF), which took over the responsibility of guarding the international borders of the country from State-armed police.

It may be mentioned that one of the reasons Punjab’s statehood was delayed was the apprehension that a truncated Punjab could not guard its border, which in 1965 extended to Lahaul-Spiti in modern-day Himachal Pradesh. That border states should be administratively compact and financially viable was also an argument of the States Reorganisation Commission (SRC), which refused to alter the boundaries of Punjab, Bombay and Assam while accepting the linguistic reorganisation of Andhra Pradesh for the Telugus, Mysore (later Karnataka) for the Kannadigas, Madras (later Tamil Nadu) for Tamilians, and Kerala for Malayalam speakers.

Shastri is also credited with laying the foundation of the Green Revolution in 1965 by giving political support to the remarkable team of then-agriculture minister C. Subramaniam, Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) head M.S. Swaminathan, and agriculture secretary B. Sivaraman. He agreed to the formation of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), then known as the Agricultural Prices Commission (APC), to ensure that farmers got the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for their crops, and was responsible for setting up the Food Corporation of India (FCI). This marked a major departure from the Nehruvian policy of privileging industry over agriculture and keeping food prices in urban areas and industrial townships ‘affordable’ even as farmers had to face the brunt of compulsory levies to stabilise the price situation.

Shastri’s dream team clearly understood that unless farmers received remunerative prices, and unless agricultural production was driven by better seeds, fertiliser, irrigation and market support, there would be no real breakthrough. His views on agriculture were closer to those of Chaudhary Charan Singh—India’s fifth PM who prioritised agriculture—than Nehru. Shastri’s farmer-led strategy helped India overcome the humiliating conditionality of the US’ PL-480, or Food for Peace Program, under which the Lyndon Johnson administration was routing its food assistance to India.

Therefore, it is high time that we reassessed the legacy of the second Indian prime minister. Readers are perhaps aware that much more has been written about the circumstances of his death in Tashkent, just after signing the ceasefire agreement with Pakistan, than about the range of institutional innovations during his premiership. His unrelenting fight against corruption and his statesmanship in resolving the language issue in 1965 deserve recognition. That, indeed, will be a real tribute to the man who steered the ship of the State at a very critical juncture in history.

Sanjeev Chopra is a former IAS officer and Festival Director of Valley of Words. Till recently, he was the Director of the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration. He tweets @ChopraSanjeev. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)