Election season is approaching and understandably there is a need to assess performance—economic and political. For political performance, the outcome of the 2024 election is not known. But we can compare the economic performance of the Narendra Modi-led BJP government with that of the previous Congress dispensation during the high growth period from 2004 to 2013. Such a comparison is useful to understand, evaluate, and compare economic policies and their outcomes on economic growth.

Historically, economies like India and China operated like isolated islands. But starting with the 1991 economic reforms, successive Indian governments have followed a consistent reform policy (with some important failures). A key outcome of the reforms process, both in India and China, has the increased integration of these economies with the rest of the world.

Now, how should economic growth across different time periods be compared? The simple method would be to compare the headline growth rates for different time periods and evaluate which is higher. However, there is a caveat. This approach assumes that growth in both the periods was equally likely. It overlooks the external conditions (like global slowdowns) that probably played a key role in influencing economic growth in a globalised economy.

Another frequently used comparison measure is to compute the potential growth rate of the economy. This is useful for determining whether the economy is in a positive or negative business cycle. Further, changes in the potential growth rate are important as they help better understand the long-term impact of economic policies (such as reforms). But how does one measure economic potential, and does that relate to the external environment?

This discussion is important because it highlights the challenges of comparing economic growth across two different periods—an exercise that analysts have been casually undertaking over the last several months. Unfortunately, such simplistic comparisons are inappropriate. In particular, they do not help in creating a better understanding of the influence of policies in shaping economic outcomes.

Also Read: India’s youth need jobs not freebies. Can govt deliver before demographic dividend fades?

‘Excess growth’ is a better metric

To address the issue of comparing economic growth across time, we propose a simple metric based on two steps.

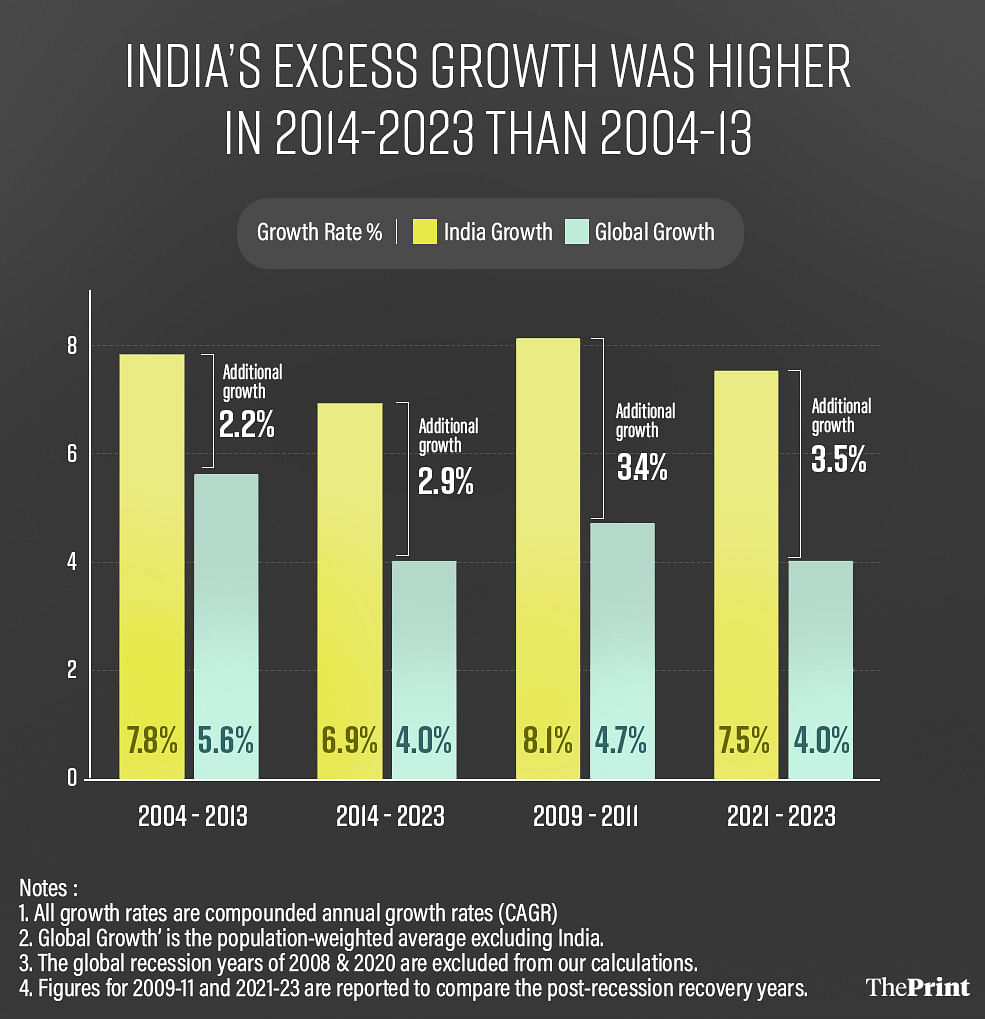

The first step is to take the population-weighted average growth of all countries, excluding India, for a given year. This gives us an estimate of global growth for that year. This captures the external growth environment—independent of India—and therefore provides us with a “reference” estimate of growth.

The next step is to subtract the global growth rate from India’s growth rate. We thus arrive at India’s excess growth. This excess growth rate is a reasonable measure to infer economic performance across different time periods. Naturally, the higher the excess growth, the better the economic performance.

Also Read: Manufacturing, investment drive India’s FY24 growth estimate, but consumption needs to rebound

India’s economic performance improved in 2014-2023

Before undertaking this analysis, a cautionary note. Both 2004-13 and 2014-23 experienced two global recessions. The first is the global financial crisis and the second is the Covid-19 pandemic. Many have compared these two events, but such a comparison is problematic on two counts. First, the 2020-21 pandemic caused a greater intensity of economic shock than the 2007-2008 global financial crisis. Second, economic outcomes during the pandemic across the world were determined by public health choices, like lockdowns. Therefore, for the purpose of evaluating economic performance across time, these two years need to be dropped.

However, the inclusion of these years does not change the key result: India’s improved performance in 2014-23 compared to 2004-13.

A simple comparison of growth rate shows a drop from 7.8 per cent in 2004-13 (Period I) to 6.9 per cent in 2014-23 (Period II). However, global growth during Period II was 4 per cent compared to 5.6 per cent earlier. As a result, India’s excess growth is 0.9 percentage points (pp) higher in 2014-23 relative to 2004-13 (2.9 pp vs 2.2 pp). Therefore, the conclusion of better economic performance due to higher growth during Period I ignores the conducive external environment that facilitated this.

It is important that commentators recognise that the changing external environment renders the comparison of simple growth rates incorrect for the purpose of comparing economic performance.

Surjit S Bhalla is a former Executive Director at the International Monetary Fund and Karan Bhasin is a New York based economist. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)