Since August 2019, much has changed in Kashmir. Many interpret the division of the erstwhile state into two federally administered territories as the ‘loss’ of autonomy and democracy, which it may well be in many respects. Kashmir’s political and influential circles, especially, are vocal in their discontent about the institutional revamping of Jammu and Kashmir. The disgruntled elite often argue that democracy is faltering in the region and that the new actions and legislations are necessarily anti-people. But ironically, much of this disenchantment comes from those who have stifled democracy in Kashmir for many decades.

This throws up an interesting question: who has a legitimate right to be angry in J&K? What can, or cannot, constitute democratic dissent in a transformative political context, and how does this impact some of the recent developments in the region? The political transformation of the state has made one thing amply clear: people have realised that the walls of the region’s power-apparatus are not as tall as they were made to appear earlier. The ‘access’ in the system was limited to a privileged few, not the average citizen. It was largely mediated and sustained through a system of patronage. But then, we have long mistaken the patronage system—right since the Bakshi period—for a democratic system.

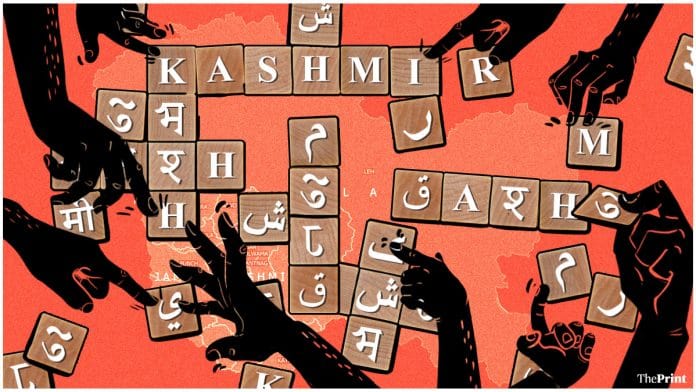

Kashmir’s ‘conflict elite’

First things first. It is hard to argue against any sort of ‘autonomy’ that might help preserve one’s collective identity. However, Article 370, often seen as a safeguard, had a major yet often overlooked downside to it. It functioned as a magnificent façade in a political milieu that kept the popular sentiment divided between separatism and autonomy.

On the face of it, Kashmir’s dominant political elite made ‘autonomy’ the centrepiece of their engagement with the people, issuing warnings about the imminent loss of ‘special status’. Yet, these political and economic aristocrats—the ‘conflict elite’—profited handsomely from central government packages and assistance. Even as the region’s public resources flowed generously to these elite circles, people were carefully led into sentimental politics instead of seeking improvements in governance.

Politicians would keep visiting New Delhi for packages, while the local elite and their kin would scavenge on the bounties. This meticulous system was created, maintained, and perpetuated over many decades, usually to the disadvantage of ordinary people, who, riding on ‘sentiment’, largely overlooked how the elite controlled public spaces, capital, and power. Those with access in the system rose to the great ‘Solomon Heights’ without much hard work.

If Article 370 was truly a bulwark against the purported influx of non-locals, why did it only serve the interests of the local elite? If the region was embroiled in a violent conflict, how did the elite get to own plush resorts, elegant hotels, and pristine lands, particularly in tourist destinations? In hindsight, all that appears patterned and purposeful.

Dismantling a noxious power matrix

Today, many decry the appointment of non-local officials at the apex of the J&K administration, raising concerns about potential prejudice and disconnect with the locals. However, this approach can also be a critical step towards dismantling the existing power structure and promoting a more inclusive political system in the Union territory.

After all, the bureaucratic elite has long served the political elite in maintaining a retrogressive power equation in the Valley, all in the name of decentralisation and autonomy. This enduring alliance between the administration and politicians, behind the façade of Article 370, has perpetuated both personal and institutional corruption.

Now, as this power matrix crumbles, the privileged elite lament the loss of democracy in the Valley—a claim that rings false and as a manifestation of political anger. The only legitimate political anger in Kashmir is arguably that of the Pandits, the territorially marginalised, and the victims of political violence.

This brings us to the question of distributing public goods to the disgruntled and marginalised sections. Many in Kashmir perceive the new policies being implemented in the UT with utter disgust and anger. But we must ask: did previous successive governments make genuine efforts to engage with Gujjars, Paharis, and other marginalised groups? As responsible citizens, we must acknowledge our moral complacency in undercutting the benefits of development to those living in the peripheries. Now that the deprived citizens are getting a share of the cake—long distributed by the elite to their inner circles— they are crying foul.

One acquaintance would often say: “Pandits have grabbed all the jobs in the last few years and the government is overdetermined to rope them in thousands.”

But there’s a simple, factual retort to this claim. Have the Kashmiris not had access to all employment opportunities for the past three decades, especially after the Pandits ‘left’ the Valley? Moral disengagement is essentially political in nature. And without reform through meticulous moral reflection, political intervention will always be needed to correct it. J&K needs a political surgery and the ongoing efforts are apt, if not ideal, for excising the entrenched and unholy elite power matrix and its strategic dens. We need to ignore the false angry voices, mourning only the loss of a system that served their self-interest.

Hits and misses

The J&K administration has controversially approved an additional 10 percent reservation for Scheduled Tribes (Paharis) and increased it to 8 percent for OBCs. This decision has been met with considerable public disenchantment in the UT. In this case, there is no point in disputing the argument that extending the reservation beyond a reasonable limit, as determined by the Supreme Court, is not only blatant injustice to the majority but an exemplar of bad political action. Unfortunately, reservations are deeply enmeshed with politics in the country and J&K is no exception. However, there is a discernible pattern that has led us into this pathological scenario

J&K’s political-bureaucratic elite played a pivotal role in extending reservations to regions labelled as ‘backward’. Interestingly, some of these ‘backward areas’ are conveniently located along national highways and in well-developed locales. Thanks to politicians who bestowed ‘political favours’ onto very select locations for political reasons and without any application of mind.

More interestingly, the lower-tier elites—doctors, engineers, bureaucrats––have invented ingenious ways to ensure that the ‘backward areas’ remain perennially so, at least on paper. They are observed relocating to urban areas to ensure the best opportunities for their children, and rushing back to their ‘backward’ homes on the weekends. In doing so, they religiously follow residency regulations to keep the window open for future reservation benefits. This is a textbook case of ‘strategic poverty’ maintained over decades. No amount of civic virtue can help us overcome this pathology, a great legacy of previous political regimes. Of course, this argument does not preclude other versions of patronage politics that equally contribute to this political pathology.

Let’s not overlook some recent positive transformations in the Valley. Over the past few decades, there have been several elected governments, and all have failed to institute an effective grievance cell.

Now, the Governor’s Grievance Cell (GGC) is a promising initiative to enhance the accountability of public officials, who previously operated without any fear of consequences. If the administration empowers the GGC to prosecute top officials, it can be an incredible example of a miniature government in itself. In order to do this, it is essential to establish a resilient institutional framework, and, of course, strong political determination. However, the biggest challenge to the grievance cell’s effectiveness comes from the civil servants who maintain it. Despite this, the public views the GGC as a step in improving the governance structures of the region.

Successive governments have been very ineffective in implementing redevelopment plans for city centres, often blaming their failures on the protracted conflict. None of them demonstrated much political will. Today, Srinagar is experiencing a remarkable metamorphosis, establishing itself as a leading Smart City in India. The city has undergone rapid development, both in terms of its visual appeal and infrastructure. Prior administrations could not have fathomed the possibility of renovating Srinagar even within a span of decades.

The city has been precisely redesigned, as visible in its new and organized landscapes, drainage systems, pathways, parking lots, pedestrian movements, and most importantly, its fully renovated public transportation system, which works citywide and runs until late at night. The new crimson buses give the city a vibrant look, reminiscent of Delhi. Srinagar has also experienced a notable decrease in ‘manufactured violence’—the era of stone-pelting, hartals, strike-calendars, and cyclic violence is long gone.

The region, especially Srinagar, is experiencing an exceptional level of stability, tranquillity, and predictability, and all of this has come about through painstaking efforts. This has contributed to a significant surge in tourist and commercial activity in urban areas. There is much more to be said, but still much more is to be done.

Aejaz Ahmad is an independent researcher based in Srinagar. Jahingeer Dar is Govt Advocate, J&K High Court, Srinagar, and a research scholar. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)