WritingsOnTheWall is a metaphor that emerged through about three decades of travel, mostly in poll-bound India. This instalment comes to you from the Kashmir Valley. It is also my first experience of watching an election in so sensitive, vital, and fascinating a region.

First, what is WritingsOnTheWall? It means literally looking at the walls to see what’s changing and what isn’t, what the people want and what they absolutely don’t want.

The walls also tell us what the people are buying (branded underwear, Nitish’s Bihar, 2010), or if they are too broke to be buying anything at all (Lalu’s Bihar, 2005). That gives a quick peek into the state of an economy, and change. In Kashmir, for the better. You can read all the earlier reports in the same series here.

In the Kashmir Valley, where two of the three constituencies (Srinagar and Baramulla) have polled already and Anantnag-Rajouri votes this Saturday, three things stand out. Or let’s say, three de-hyphenations stand out, although you can read only one of these straight off the walls. For the other two, you have to step inside them.

Here are the three de-hyphenations: first, the youth, who constitute a significant section of Kashmiris, have de-hyphenated their minds at least for now from the politics of radicalism, separatism, anger and grievance. Don’t be deluded into believing that it is all over. It sits there and comes out when young people think they can trust you enough and talk. The priority for now is education, competition, jobs and careers.

Second, there is a striking de-hyphenation from Pakistan. Its political crisis, Imran Khan’s incarceration despite his popularity, and economic collapse are important talking points. It also comes from the simultaneous phenomenon of the catastrophic decline in Pakistani national power and the rise in India’s.

And the third, at the tactical and ground level, is the security agencies’ success in de-hyphenating weapons and the people. Everybody knows there are plenty of weapons in the Valley, and still many who are trained and motivated to use them. But that cord has been cut for now, or de-hyphenated. The likely users can’t get to the weapons and vice versa.

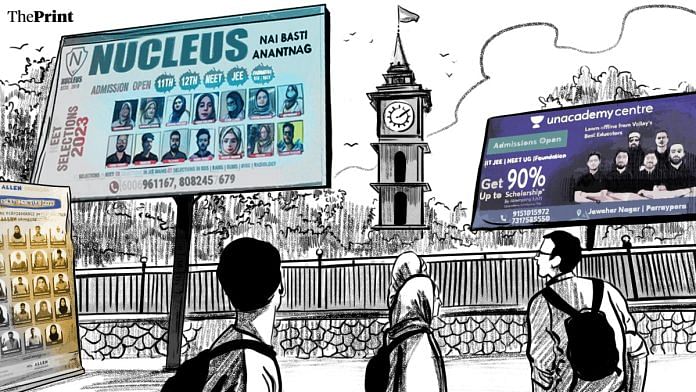

You can safely say that in most parts of India, except probably some states in the north — especially Punjab, where immigration/visas/IELTS dominate — the walls are generally filled with hoardings and posters of coaching academies.

I do not think, however, that they are as prominent anywhere as in the Kashmir Valley. Allen Career Institute, Chanakya IAS Academy, Elite IAS, Emerge Institute of Coaching, The Commercians, Vedantu, Nucleus Institute Of Excellence — literally scores of brands fills the walls, trees, unipoles, just about any place you could hang or stick anything on to.

Everybody wants to crack UPSC, NEET, JEE, all the things young people across the country covet. So many of these hoardings have portraits of their successful students. This is the post-stone-throwing generation of Kashmiris. They are also the Valley’s new future.

I messaged my old friend and fellow traveller Uday Shankar — yes, formerly of Star-Disney, now a formidable entrepreneur — to tell him I see so many hoardings of his new coaching academy venture, Allen, that perhaps the place should be renamed the Valley of Allen or Allenistan. He told me with pride how many young Kashmiris are cracking these exams to become doctors, engineers and so on.

If you were one of those still nostalgic about the heyday of militancy and separatism, you might call it a great distraction. Even if so, there couldn’t be a more virtuous distraction. If so many tens of thousands of boys — and girls — want to compete with the best and look for careers in the rest of the country, it’s the kind of change not even a doubling of defence budgets, or a law thrice as tough as UAPA, could bring about.

Also Read: Yogi’s cows, Modi’s houses, Akhilesh’s jobs: Why this is a more ‘normal’ Uttar Pradesh election

Take nothing for granted

The walls also give us the starkest evidence of what hasn’t changed, and the tensions that lie within. Walk along Gupkar Road, where the mightiest in Kashmir live. That’s why the alliance the key Valley parties once formed was called the Gupkar Alliance.

Each ‘home’ is a fortress, with reinforced concrete walls going up to 18 feet and sometimes more. On top of a wall, you might find strengthened steel sheets, crowned with rolled concertina fencing. This adds up to an obstacle so high even a great pole vaulter like Sergei Bubka would struggle to clear over it. This isn’t about to change any time soon. As I am schooled by Farooq Abdullah for almost two hours under a tree.

Things are better, he acknowledges, violence is not there. But that doesn’t mean young people aren’t angry. They see Delhi as ‘vindictive’. Too many are imprisoned, sent to jails in faraway states. My best effort at a translation and summary of this calm tutorial over a bowl of fresh, chopped strawberries would go: Peace is alright, but where is the peace dividend? Things are better, people are appreciating peace and illusions about Pakistan are over. But take nothing for granted.

A lot of what he talks about is history, the many twists and turns over the decades since he began his public life as a subaltern to his father.

Approaching 87, he is one of the senior-most, oldest (and yet among the most energetic and passionate) political figures in India. That passion speaks out when we return to Article 370. “They say that after abrogation, we Kashmiris have become Indians. Are you telling me we weren’t Indians before?”

I do my best to persuade him to finish the memoir he keeps talking about, because as with any chronic geopolitical and emotional issue, the past is very much a guide to the future. We all need to learn more from him, and truthfully. For example, the rigging of the election in his favour under Rajiv Gandhi in 1987, which he denies. If we had rigged it, he says, how come Ali Shah Geelani and four others from his side were elected nevertheless.

The comrade who survived

Another Kashmiri political veteran who should be writing a sizzling memoir, though from an ideology you wouldn’t expect to find here, is Mohammed Yousuf Tarigami. He has kept the flag of the CPI(M) aloft in the state for many years, winning elections to the state assembly often. He was noted and marked out as a left activist first when he joined protests for Palestine sparked by the six-day war in 1967.

Spend an hour with him and he will tell you of the many attempts on his life, including one where nine next to him in a tiny rally were killed. And of one of his several incarcerations, where the jailer summoned him one day to say he was being given parole, though he hadn’t asked for it. The reason was that his wife had died delivering their first child. He married again, but later his father-in-law was killed as well. Never short of courage, the comrade, at 77, acknowledges the improvements, the respect for law being the most important. The government, however, needs to move on, he says. From the mode of “managing” to that of “engaging”.

You want to know what courage is? It has to be physical as well as moral and philosophical. He will call out the entire Left-liberal community that still blames then governor Jagmohan for triggering, even sponsoring the plight and flight of the Kashmiri Pandits. “I have never said so, and never will. They were driven out by the militants,” he says, and reels off the names of prominent Pandits killed, the biggest massacres and atrocities. Including Neelkanth Ganjoo, the sessions judge who had sentenced JKLF’s Maqbool Bhat to death and who we’ve forgotten all about.

Tarigami, too, lives in a fortress like the other key leaders. He also tells me wistfully the story of “how and why I was given this bungalow”.

That’s the story of many attacks on his life and near things. This is the story of everybody who’s been in public life in Kashmir, without exception. That’s why it’s even more creditable they hang on, keep a political process going, and are national treasures.

Also Read: Modi’s Hindutva 2.0 written on Varanasi walls: Temple restoration, not mosque demolition

Toughest job in India

What’s the toughest job in India? The most challenging, dangerous and ultimately thankless? Short answer, it is to be the governor (now lieutenant-governor) of Jammu and Kashmir. It’s an incredibly beautiful Raj Bhavan. It could also be the prettiest prison in India.

A lot of power resides here, though. Manoj Sinha, the dhoti-clad politician from eastern Uttar Pradesh’s Ghazipur, sports a generous tuft and a constantly buzzing mind. As chief administrator of the Union territory with no elected legislature, he is probably the most powerful official in the country. He lists the things he has done to straighten things out. Denial of jobs to the immediate family members of top militant/separatist leaders being one. “This is how crises were resolved in the past,” he says, referring to how jobs and contracts were offered to separatists’ families in return for a respite from hartals and stone-throwing. It is over now. His administration has found all such employees after a thorough search and used Article 311 of the Constitution to fire them.

It is a territory of about 1.35 crore people with 4.8 lakh sanctioned government jobs. Another 1.27 lakh are routinely hired as daily wagers with written commitments for confirmation after seven years. The place was a racket. But there weren’t any other economic opportunities either. Compare this with Bihar’s 5.17 lakh sanctioned jobs for an estimated population now of about 14 crore.

People didn’t come to work, or just came in the morning and evening to mark their attendance. Now, Sinha has brought in facial recognition and controlled the hiring. More importantly, all government contracts are now e-tendered. No more informal word-of-mouth contracts with no paperwork.

“When I came here, I received a call from Digvijaya Singh, who said some acquaintance of his had done some contract work here and wasn’t yet paid for some eight years,” Sinha said. And then Devendra Fadnavis called for similar help to get money owed to a constituent of his released. Sinha said his officers found no records of these contracts having been given, or jobs carried out. It was all done in the air, he says.

‘Normal’ like any any other part of India

Evidence, again, speaks from the walls. In the political, social and cultural heart of Kashmir, Srinagar’s Lal Chowk.

In New Market, one of the quaint lanes leading to the Jhelum River from Lal Chowk, I find a shop with a sign that simply says “E-Tendering”. Inside, the owner, Owais, sits with four computer screens in front and two heaps of what look like keychains, but are actually DSCs (digital signature certificates).

His business is helping people file e-tenders and his clients — hundreds — have left these DSCs in his care. He tells me he used to be in the garment business earlier. At just Rs 200 per e-tender, he says, it has more remunerative possibilities than garments. Whatever happened to the old business? I ask. It was the same shop, he says. It is now an e-tendering enabling business.

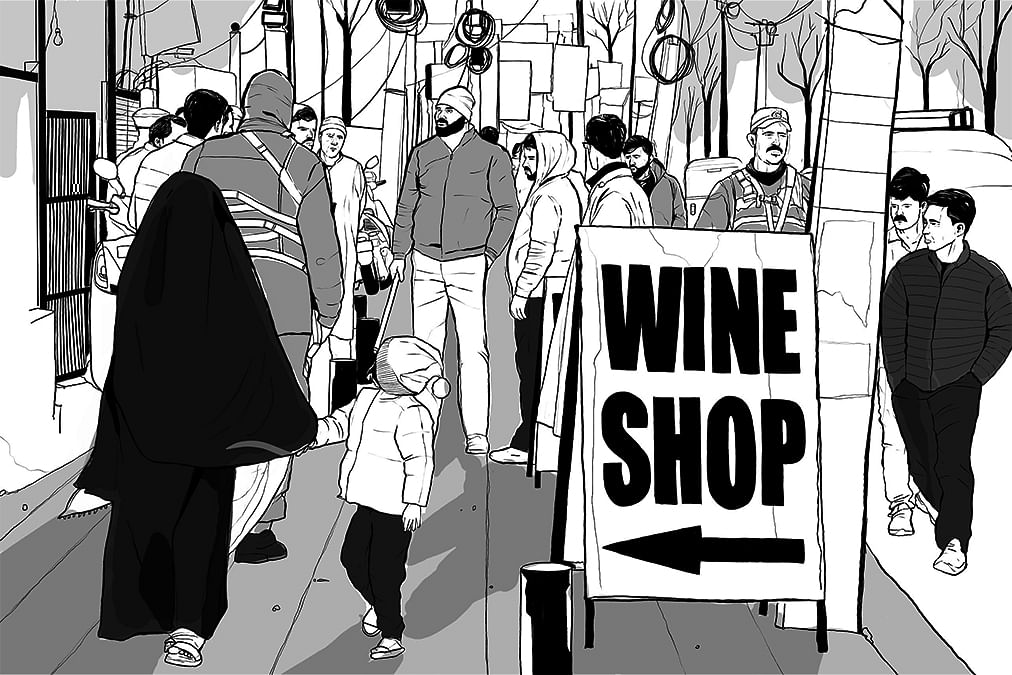

He’s pushing social change, too. Earlier, he says, Jammu and Kashmir’s excise revenue was just Rs 6 crore. Now it is 365 crore. How? Because he pushed for liquor licence options. Now there are 14 liquor shops and he’d like more. It should be a ‘normal’ place, as in any other part of the country. Except, of course Bihar and Gujarat, would be my somewhat snarky, but truthful, aside.

Lal Chowk itself is filled with tourists, posing for selfies and group photos while some paramilitary troops watch unobtrusively, if warily. A dozen well-fed dogs lounge as the cats might at Istanbul’s popular spots. The old Sanatan Dharma Dharamshala, the most imposing structure overlooking the storied clocktower at Lal Chowk, is being reconstructed at the kind of speed at which Nitin Gadkari has been building highways.

A walk around the corner from it takes you into the heart of what was among the toughest of protest zones, from Maisuma to Gawkadal, where a Jhelum tributary meets its big sister. Gawkadal, incidentally, is the place of the great massacre on 21 January, 1990, when 50 to 100 Kashmiri protesters — more likely closer to the higher figure — were killed in a CRPF firing. This was the fraught era when the Pandits were being driven out, the new militancy was operating, and the state looked barely in control of the banks of the Jhelum.

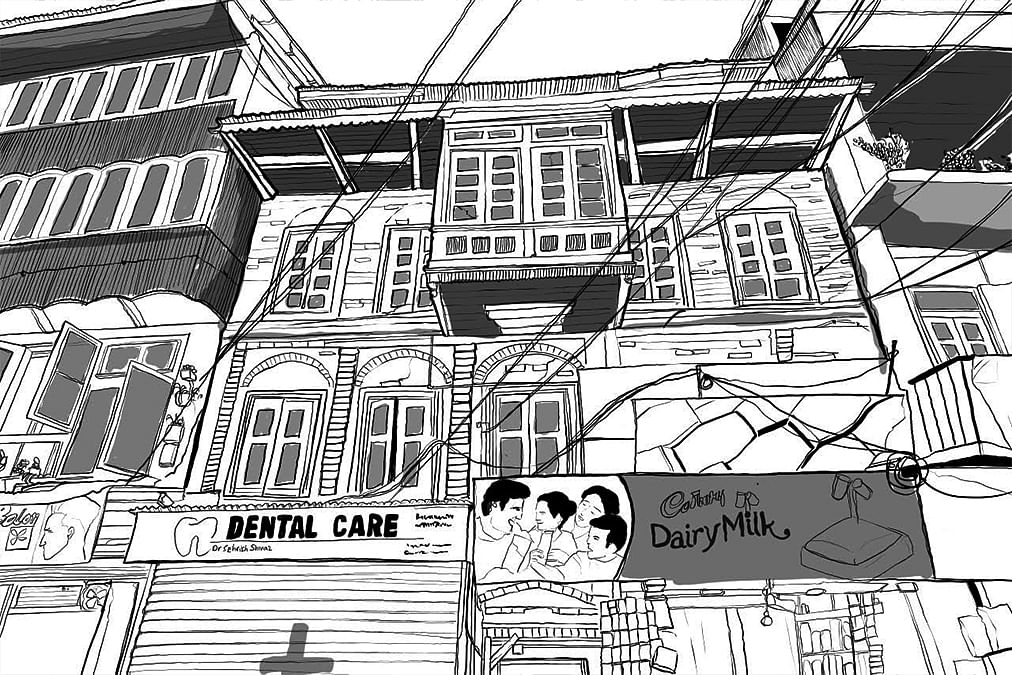

Many would be embarrassed to admit it now, but too many in the security system, and also those on the BJP side, would simply call it the “Pakistan in Srinagar”. Walk with me here, through lanes lined by beautiful old homes and wooden balconies (jharokhas) with their ornate windows, stop at the many tiny bakeries, pick up a lightly salted tea bread (namkeen) and people will walk up to talk about the sorry state of the “you” news media, and how tough it must be for the “few truthful ones” to keep it going.

These conversations take place almost across the street from the native home of separatist Yasin Malik, now under trial for the murder of four Air Force officers on 25 January, 1990. And such conversations could have taken place in any part of Lucknow, Patna, Amritsar, Coimbatore, Hyderabad, Bengaluru, Kolkata. Just anywhere in India.

Also Read: Bengal stands up to ask for more

77-year blood feud over the Valley

The Kashmir Valley is actually quite a small piece of territory, 135 km at its longest and 32 km wide. It is broadly divided into three zones: the northern one going to Uri via Baramulla, Gulmarg, Sopore, Kupwara, Gurais and so on. The central one, with Srinagar and adjoining districts. And the large expanse of the south, with Anantnag, Pulwama and Shopian.

From Shopian begins the old, Jahangir-era Mughal Road taking you across “the hump”, the Pir Panjal range through the eponymous pass into Poonch, and then on to Rajouri and Jammu. Poonch and Rajouri have now been added to the Anantnag constituency (polling Saturday) rendering it no longer a “pure” Valley seat. Some of its original assembly segments have gone to Srinagar, Pulwama and parts of Shopian.

With 72 lakh people, it is also quite thickly populated, endless rows of orchards and paddy fields dotted with small towns and villages that are still faithful to the traditional architectural aesthetic even in new constructions. Kashmir’s villages are also among the cleanest in India.

I use a much-maligned ploy from the reporter’s playbook and ask my driver how come there is so much new construction, so much apparent prosperity in the Valley? Where does it come from? All those building these nice houses now, he says, have made money from “both” sides.

What looks good in the Valley, in fact, also tells us what’s so wrong with it. The most profitable business in these decades has been what we might call conflict entrepreneurship. India and Pakistan, militaries, diplomats, but most importantly intelligence agencies, have fought a 77-year blood feud over the Valley. Both have had plenty of cash to dispense, and on the Indian side, the establishment has tended to look away as the smartest — including politicians, businessmen and generations of government officers — have vacuum-cleaned the money the Centre keeps throwing at the problem.

Almost all Kashmiri politicians and their dynasties have benefited from the conflict. None except the Abdullahs have been found to willingly say they are Indian and that there is no future for the Valley except as an integral part of India. Others find profit in ambiguity. Some of that is changing.

Congress-NC, Apni Party & PDP

The Modi government has had five years to build a new political class in Kashmir, but failed at it. So stark is this failure that it isn’t even fielding candidates in the three seats of the Valley. Before you jump up and say ‘nor is the Congress,’ I will remind you that its partner, the National Conference, has been allocated the three Valley seats. The Congress is contesting two in Jammu and the solitary one in Ladakh.

The Centre could have built a new grassroots politics if only it had succeeded in holding the panchayat elections. But for that, the law would have had to be amended to give reservations to Scheduled Castes and Tribes, which needed a constitutional change through Parliament. Nobody in New Delhi found the time to do it in five years. The Centre, therefore, decided to do it top-down. It looked for native talent to create new parties and counter the established ones.

For evidence, check out what Home Minister Amit Shah has been saying: Vote for anybody you wish, but not for the National Conference (Abdullahs), the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP, the Muftis) or the Congress. Translated, it means, vote for the Apni Party, founded by hugely successful entrepreneur, former Mufti loyalist and minister Altaf Bukhari. Bukhari is a graduate of agricultural sciences and a diploma-holder, he says, from Delhi University’s formidable Faculty of Management Studies (FMS), “1980 batch.”

He has businesses in the Valley, but most of his fortune comes from elsewhere. From his agrochemicals plants in Gujarat’s Valsad, for example. He also builds and installs India’s largest gondolas (cable cars). One from Dehradun to Mussoorie is near completion. His next big one will be a city connectivity project in Varanasi, a place as flat as you can find. Many Kashmiris, old and young, will tell you his party is the establishment’s party, a front for the BJP.

“Are you close to the BJP, are you working with Delhi,” I ask him during a campaign break at the village of Brenti Bat Pora near Anantnag, while he feeds us a full Kashmiri meal with multiple dishes of meat garnished with some usual lotus stem and paneer. “Of course I am. I am never shy of saying that. Who will you work with if not with Delhi? Will it be Islamabad?” he asks.

Kashmir as ‘IPL’ with same franchises, shifting players

Kashmir’s tragedy is that everybody works with Delhi but pretends they don’t. And they keep looking at the other side, too. That has to change now. The future of Kashmiris lies in working with New Delhi and giving up all ambiguity. That’s his view. Is Bukhari going to win? Of course he’d say he will. But he doesn’t seem overly concerned if he doesn’t.

He sees a new future for himself. This is the closest you’d see to an old-fashioned king’s party. All he wants the Centre to do right now is to look kindly at people it has punished. The thousand-plus in long detention, many in jails in faraway states. It is all about making peace with the young people, he argues. Not one of the stone-throwers or militants was older than 20 or so. They have a full life ahead of them. He then introduces his followers who have to report at a police station every evening because they were found indulging in stone-throwing in the 1990s.

We hear similar words from some of his younger, equally articulate rivals. Waheed-ur-Rehman Para of Mehbooba Mufti’s PDP is asking for a reconciliation process, an amnesty for the jailed youth. He used to be a key aide of Mehbooba when she was chief minister in partnership with the BJP. He has spent the better part of the past six years, since that coalition broke, in jail, with the charges against him including terror funding. “We accept the Constitution, we accept India, where is the problem then? Why won’t the Centre trust us?”

The second is Sajad Lone in Srinagar. He’s revived his slain father’s People’s Conference, is contesting from Baramulla and is seen as favoured by Delhi. His father Abdul Ghani Lone was a founder and key figure in the now-banned and defunct Hurriyat. He was assassinated, obviously on the orders of the ISI.

There is also the top cleric in the Valley, Mirwaiz Mohammed Umar Farooq, still in some kind of house arrest, or at least restraint. I spoke with him on the phone and he said that while he would love to meet, he wouldn’t be permitted to. As in, I wouldn’t be allowed into his home as his interactions have been limited to close relatives. Like Lone, his father was also a founder of Hurriyat and assassinated at the ISI’s behest. At one point in the past the father had also joined hands with Farooq Abdullah in what was called the “Double Farooq” arrangement.

You can find a thousand Kashmir experts. But anybody halfway honest will tell you its politics confounds them. Think of Kashmir as an IPL equivalent that’s gone on for 77 years, with the same franchises, shuffling the same players. In the course of time, you’ve forgotten who’s been in and out of where and when. Even Google is confused.

A new player has risen in this old gathering. Sheikh Abdul Rashid, mostly known as Engineer Rashid, has been in jail for five years on charges of terror funding. He is contesting the Baramulla seat from Tihar. He’s drawing the largest, most enthusiastic crowds. Responses to his absentee campaign, led by his college-going son Abrar Rashid, have been nothing short of messianic. The slogan is “zulm ka jawab vote se” (we will fight oppression with votes).

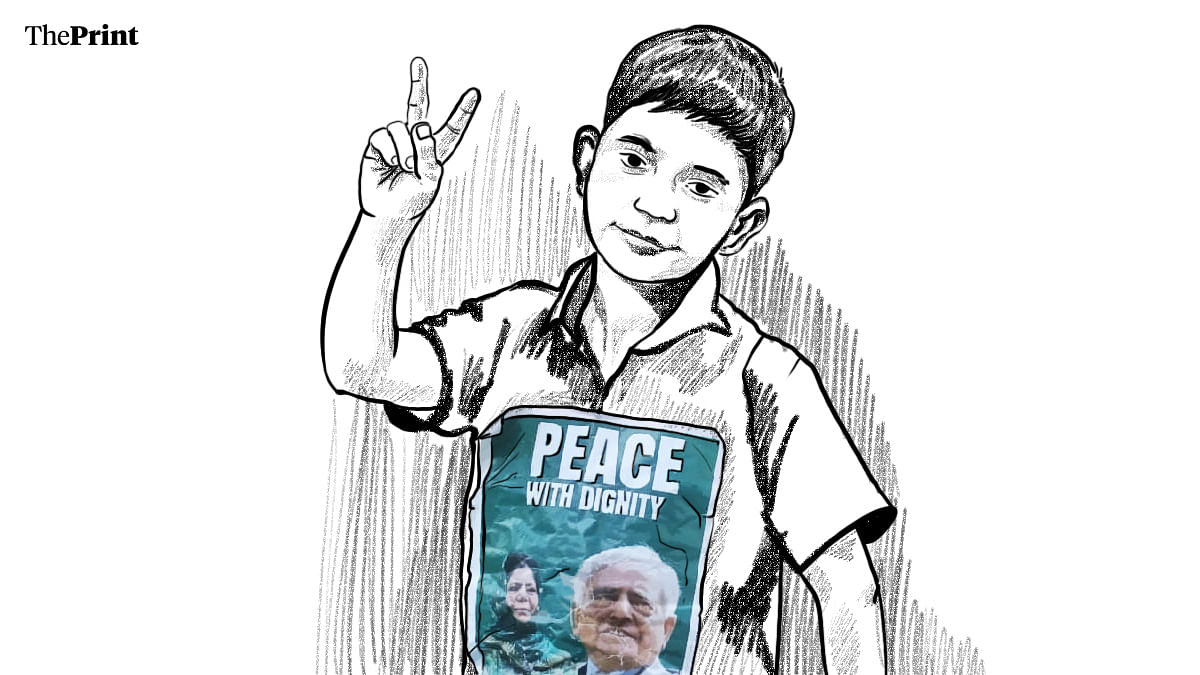

At a PDP rally, I find a child with a “peace with dignity” poster on his T-shirt, giving a ‘V’ sign for Praveen Jain, our photo editor. The unprecedented voter response in this campaign — the highest everywhere since 1996, and the highest ever in Baramulla is telling us something. As is a coaching centre called Hope Academy in Anantnag and lively café Cuppa Curiosity in Baramulla.

It’s all very good, or so far so good. Just don’t rush to conclude that it means the problem in the Valley is over. That will be over-interpreting a positive change. This voting has given a quietened people a new voice, an outlet and also an opportunity to vent — if only through the vote. It is one giant catharsis. And it is still a work in progress.

Also Read: Stumbling on Sonianomics in the land of angrezi dreams