Ever since the intrusion in Ladakh last year and the subsequent rise in border tensions at the Line of Actual Control, the Indian commentariat has tried to decode the Chinese strategies with specific references to 1962 and later. What has been less talked about is India’s border policy pre-1962 and the people who worked to build relationships and not simply impose policy from a faraway capital. That era’s border policy was significantly shaped by the now-disbanded Indian Frontier Administrative Service – a special cadre of trained officers who served in frontier areas and oversaw the North-East Frontier Agency (present-day Arunachal Pradesh) as well as other regions along the India-China border.

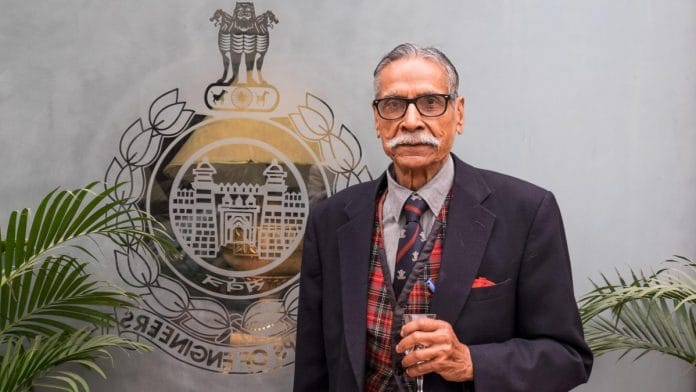

The Indian Frontier Administrative Service (IFAS) was formed by first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru in the early 1950s. The foreign secretary was its chairperson and the select few who got enlisted in the cadre were from the IFS, IAS and IPS, their deployment rotating between remote tribal areas and embassies. My grandfather, Major Krishna Chandra Johorey (KCJ), who passed away on 31 December 2020 and in whose memory I write this article, was part of the first batch of 14 men selected to serve in the IFAS, all from Army background. Although the IFAS was disbanded in 1968, some of its core concepts are worth revisiting today, especially since frontier regions continue to feel a sense of neglect that I noticed during my extensive travel in the region, a disconnect that was not always felt – adding layers of complication to the border issue.

A relationship cultivated over time

Like many men of his time, KCJ was taken up with the ideals of the leaders of the freedom movement, and left home and a potential law career in Allahabad to join the struggle. In the days after Independence, KCJ joined the Indian Army and served in the engineer corps as a Bengal Sapper, first sent on active duty to Kashmir and later to the NEFA where he spent the better part of almost two decades. In 1953, he was selected for the IFAS – a job that required a certain understanding and connection with the region and its people, which KCJ seemed to inherently possess. He and Captain Utankamoni Chakma were given the charge of the Siang Frontier Division with Along (present-day Aalo) as a base, beginning what can only be termed as wild and wonderful life and career. Through the 1950s and the ’60s, KCJ and his wife Sudha lived and served in some of the remotest parts of what is now Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Nagaland, Sikkim, Bhutan and Tibet.

It was during this time that KCJ and Sudha were first introduced to the Dalai Lama in Delhi and were posted in Tibet in the late 1950s, along with IAS officer P.N Kaul and Maj. S.L Chibber. KCJ and Sudha took Nehru’s mandate to the IFAS very seriously, working with the tribal groups of the region with great care and friendliness. My grandmother was equally popular, setting up schools and teaching wherever they were posted. While the mission was never to ‘counter’ the Chinese, they and many others, including Lt. Col. Rashid Yusuf Ali and Maj. Ralengnao (Bob) Khathing, not only made the frontier regions their allies but worked to tackle the numerous administrative and social issues with compassion. From Along, KCJ was sent to Khonsa at the Burma border, and then to Bomdila in 1961 and other sensitive areas, with postings in Tibet. With their travels, they were also mapping the region on horseback, marking roads I have travelled almost 60 years later all the way to Bum La.

Also read: Indian Army’s dash to Dhaka in 1971 was operational brilliance. It holds lessons for Ladakh

Bond with the Dalai Lama

As the Chinese aggression during the mid and late 1950s worsened, KCJ was one of the last Indians to leave Yatung, Tibet, not only ensuring that all the Indians had been safely dispatched but also aiding the Tibetans who sought refuge, especially once word about the Dalai Lama’s journey to India got out. Using diplomatic immunity, a hugely pregnant Sudha was also instrumental in bringing back to India books, papers and artefacts of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan people, many of which are now on display at the museum in Dharamshala.

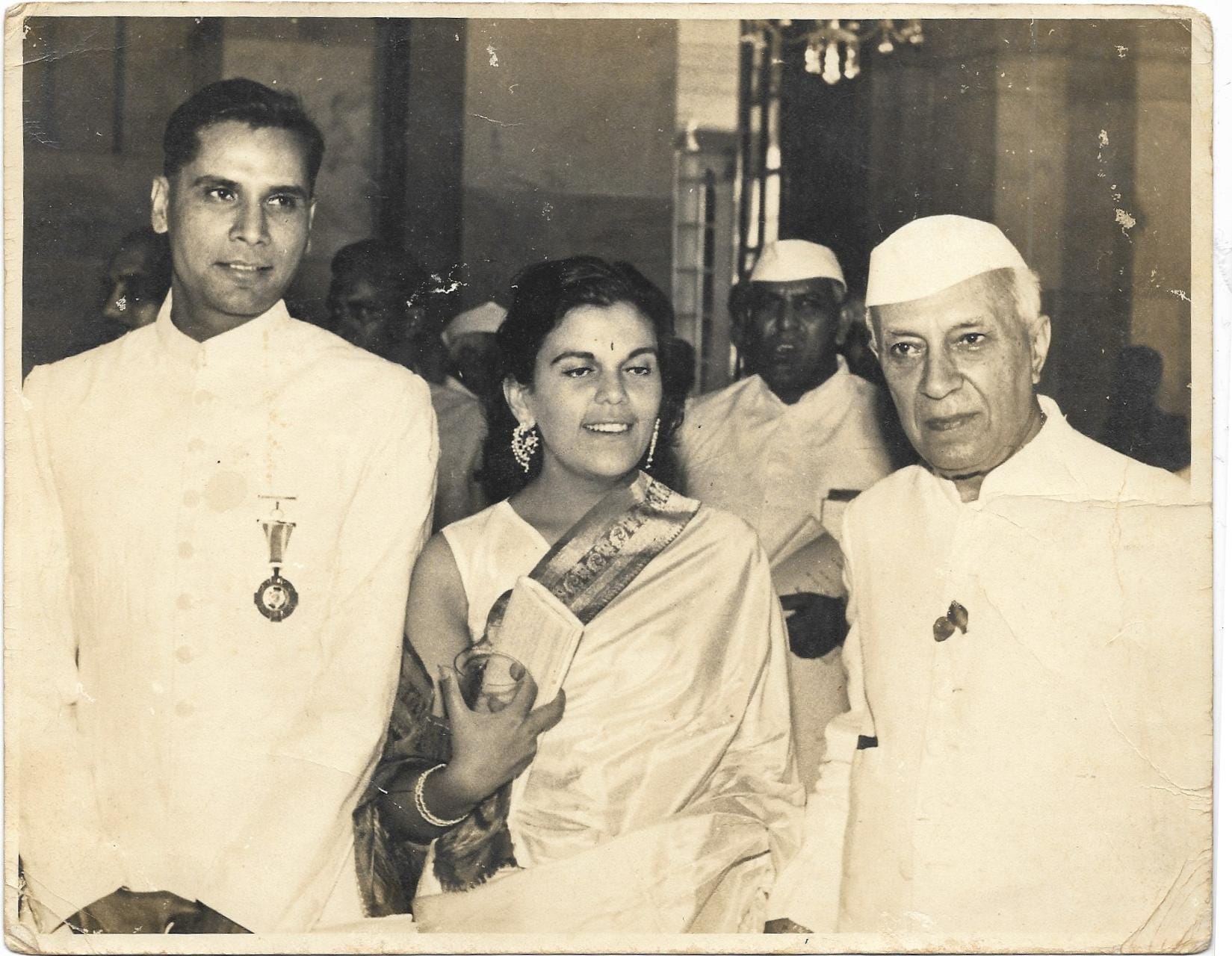

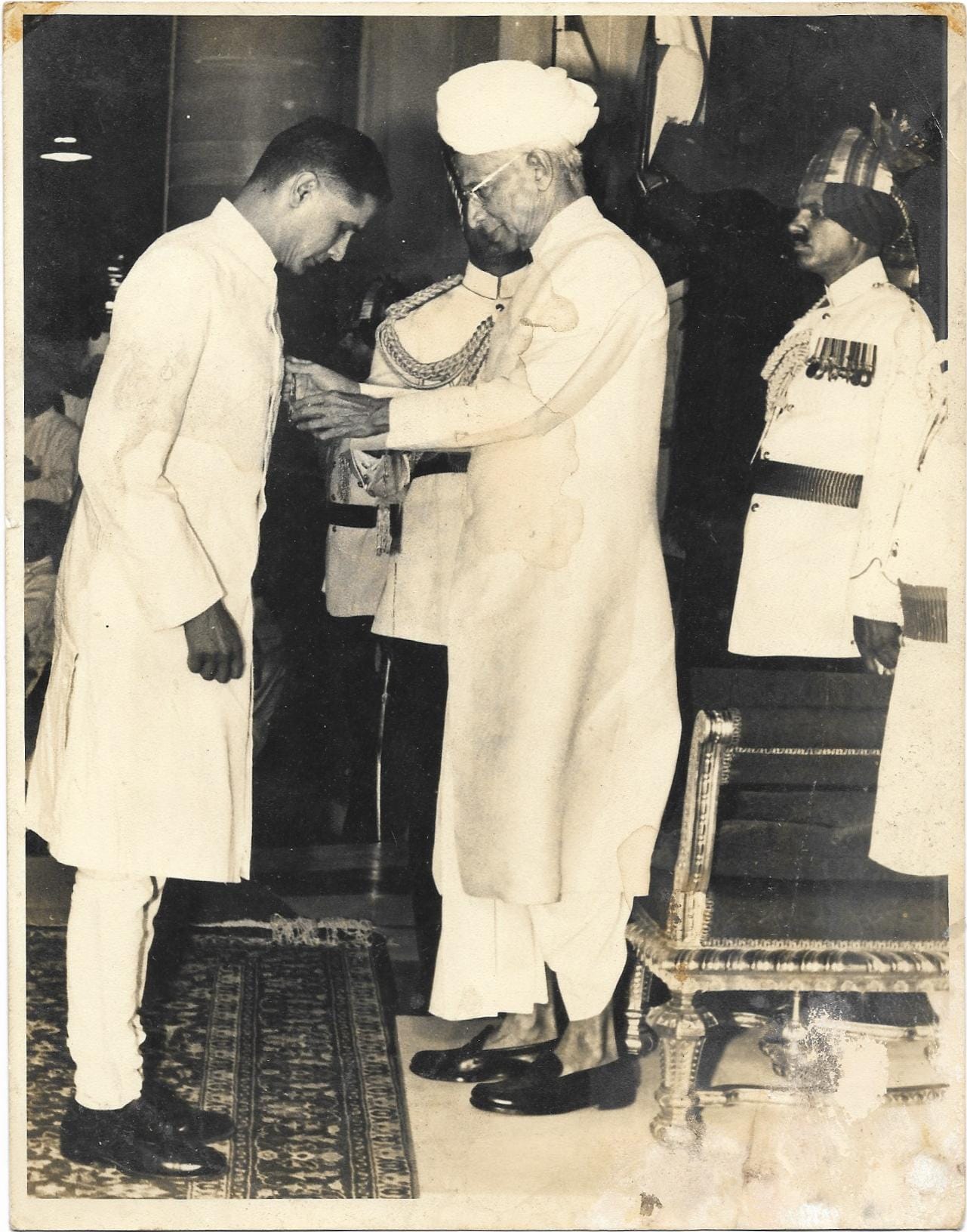

KCJ’s deep connection to the region never waned and he continued to aid the state governments and civil society in whatever manner he could until the very end. In 1963, KCJ was awarded a Padma Shree by then-President S. Radhakrishnan for his bravery and services rendered, and also received a special mention from PM Nehru, whom my grandparents had met and hosted several times, including in Yatung and Bomdila.

After spending almost 15 years on the frontier regions of the north and northeast, including time in Bhutan and Sikkim as a political counsellor, KCJ was posted in Afghanistan as the first secretary and became witness to a unique period of the country’s history in the late 1960s and the early ’70s. He continued to work within both the IFS and IAS, owing to his unique training and ability to examine critically political strategy and responsibility, a core characteristic of IFAS officers. He had one last station in the northeast, as divisional organiser, Village Volunteer Force, Manipur and was later made chief secretary of Goa in the late 1970s, along with various stints in the national capital.

Also read: India has forced a stalemate in Ladakh. That’s a defeat for China

The life I learned about later

KCJ led a remarkable life, and there are stories and accounts of official visits to Russia and possibly other Western countries, the purpose of some we were never privy to. Many periods of his life and career remain cloudy. On 31 December 2020, KCJ took with him many secrets, including the burning or successfully hiding of many official documents from India House, Yatung, to ensure they did not fall in the hands of the Chinese; serving and protecting his country till the very end.

It was only in 2005 that I truly began to understand the extent of my grandparents’ service to India. That summer, I travelled with the family and a couple of friends from the US to Dharamshala for a private audience with the 14th Dalai Lama. At Pathankot, we were met by representatives from the Tibetan government-in-exile and taken to the Army guest house. Holidays with my grandparents meant stays either at the Army guest houses or state bhavans, so none of that was unusual. What one couldn’t quite comprehend was sitting in the living room of the Dalai Lama the next day and seeing my grandparents and him chatter away like old friends, each trying to get a word in. There was much laughter and stories of Tibet and Sikkim, shared experiences and a common love for a region and people under turmoil.

I had grown up with the exciting stories of a life lived in faraway places, famous people and embassy events, with a constant theme of helping people and serving the country. On that day, all those fascinating tales came to life. Tales that I had heard during summer drives and mountain vacations or playing in the backyard in the winter sun while my grandfather read stacks of newspapers, or over drinks at the club when I was older with other equally interesting men and women from the services. As I progressed in my own life in the larger space of public policy, the ‘stories’ I grew up with took on a different meaning. I will always remember the day I met the Dalai Lama for obvious reasons, but also because on that day, my funny storytelling grandfather transformed into a guide and constant source of inspiration as I navigated a somewhat similar space.

The author is the founder director of Kubernein Initiative and a transboundary water security and diplomacy specialist. She tweets @theidlethinker. Views are personal.

Thanks, Ambika, for bringing him back to life. I have met Major Joherey a number of times , the last in 2014 in Roorkee. He was there with his wife and granddaughter ( I don’t know if it was you).

He stood out in any crowd. All of us , the Bengal Sapper fraternity will this great man.