After the water level at Nagarjuna Sagar dam dropped below the minimum level mark in 2015, a Megalithic burial site with over 200 graves reemerged. Officials from Telangana’s Department of Archaeology and Museums dated these stone circles from around 1000 BCE to the 2nd century CE. This news served as a reminder to everyone, archaeologists in particular, that the construction of Nagarjuna Sagar (man-made reservoir) and the dam over 60 years ago had submerged the ancient capital of Ikshvaku dynasty, Vijayapuri.

The government of India had proposed various initiatives in the nation-building process, including the construction of dams and reservoirs like Nagarjuna Sagar that facilitated irrigation. In such a perilous circumstance, cultural conservation, particularly of archaeological assets, may have fallen to the bottom of the priority list. However, this challenging position led to the emergence of a new kind of archaeology in India that offered room for both tradition and advancement.

In the 1950s, salvage (or rescue) archaeology helped not only in collection of ancient relics or documentation of monuments and buildings but in the case of Nagarjunakonda paved the way for transplantation and replication of now submerged relics. Today, on an island in the middle of the reservoir, there is an open-air museum of salvaged ruins and replicas of the monuments and structures unearthed during the excavation.

The resurfacing of 200 burials at Nagarjuna Sagar are a reminder that there is more to the story of this archaeological site. It gave us an important tool of salvage archaeology that should be applied at many sites.

Also read: It took 40 yrs to find first traces of Ashoka’s Pataliputra. Now, we must find the rest

Discovering ancient Vijyapuri

In March 1926, the discovery of archaeological riches in the valley of Nagarjunakonda (Nagarjuna’s Hill, named after the celebrated Buddhist philosopher) were reported by AR Saraswati, an assistant to the Archaeological Superintendent for Epigraphy, Archaeological Survey of India. The site, situated in the Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh, was then surveyed by archaeologists before the first round of excavations were initiated by AH Longhurt in 1927. Longhurst’s excavation continued till 1931, which yielded a number of Buddhist monasteries and other monuments besides numerous limestone sculptures. In 1938, another round of excavation was initiated by TN Ramachandran, which furthered the findings of Longhurst. These initial efforts brought to light the lost city of Vijayapuri.

However, by 1950-1954 the agenda of the authorities sealed the destiny of this archaeological site. Construction of a dam was proposed in the valley, which meant that the site and the museum that was created after the initial excavations would now be submerged. But given the important historicity of the site, an exhaustive effort was made by an Archaeological Survey of India team, headed by R.Subramanyam, that lasted over six years.

Nagarjunakonda during the ancient period came to the limelight when Vasishthiputra Chamtamula, the founder of Ikshvaku dynasty snatched it from the Satavahana dynasty in 2nd quarter of 3rd c. C.E. The illustrated expanse of Ikshvaku was evident in the excavations that unearthed Vijayapuri on the right bank of Krishna River.

The city has a thought-out plan within which civic needs and security was given adequate importance. Remains of an enclosed citadel that had rampart-walls on three sides and two gates were revealed during excavations. Traces of moat just outside the rampart could be traced at certain places. The structures inside the citadel consisted of residential buildings, barracks, stables, baths, wells and more. Outside the citadel, residential complexes of commoners were in a linear pattern with broad roads intercepted by cross-roads and by-lanes. The houses of common folks were identified mostly by rubble compound walls. A few enclosed houses shared a common veranda.

Apart from secular structures, the valley also constituted many Brahmanical temples situated around the citadel. These temples were not only beautifully decorated but inscriptions found there offered adequate information for reconstructing the historicity of the site. Besides these, the site was also rich in Buddhist establishments, more than 30 to be precise, that came up within the span of a century.

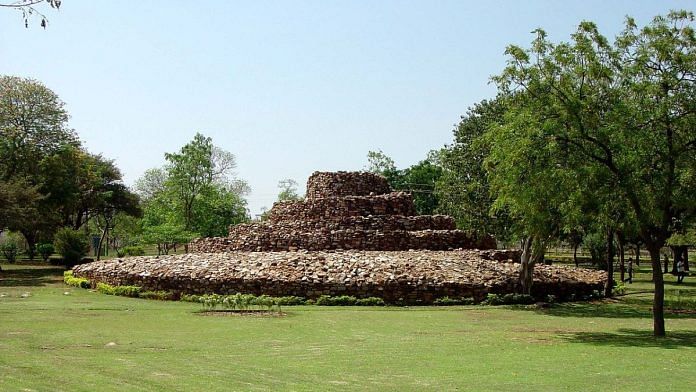

A common feature that was noted during the excavation was that most of the Stupas were built on a square platform, flanked by two apsidal shrine and a quadrangular monastery and surrounded by Ayaka platform (pillared platform) at four cardinal directions. Amphitheatre and ‘Hariti’ temple are one of the important structures unearthed during the excavations.

The most interesting feature that emerged during the excavations was that along the river banks and in and around the citadel, several wells, water tanks were constructed. It suggested that Ikshvakus made great efforts in tackling water-problems similar to what the government of India did centuries later.

Also read: How the 2008 Alamgirpur re-excavation challenged timeline of mighty Harappan Civilisation

Rescue and relocation

Salvage archaeology often involves the transplantation of ancient monuments to a safer area. It ensures that cultural resources that are likely to be impacted by constructions are properly documented and excavated before they are destroyed.

The salvaging operations at Nagarjunkonda were the first of its kind in India. For the first time such a large-scale operation that included excavation, documentation, archiving and then salvaging and replicating the remains at the different areas was an exhaustive exercise.

Nine monuments of gigantic proportion were reconstructed in the original form and alignment to recapture the essence of architectural traditions while fourteen large-scale replicas of excavated remains were displayed in the open-air museum.

The monuments that were relocated included Maha-Stupa, which contained the relics in a casket. The stupa is wheel-shaped with Ayaka pillars in four cardinal directions. An apsidal shrine, which is named after its builder Bodhisiri (3rd.c. CE) that was originally part of a monastery is also relocated.

A bathing ghat, an Ashvamedha complex, Bahusrutiya vihara, Hariti temple dated to c.4th -5th CE, the Amphitheatre and Megalithic burials are also some of the important monuments that are relocated.

Saving the past

The case study of Nagarjunakonda is comparable to the rescue efforts made in Nubia, Egypt. The potential of the site is narrated through the reporting and recording of over hundreds of sites, spanning from the Early Stone Age to the Neolithic, Megalithic, and historical and medieval periods during the last rescue operations. The invaluable result comes from meticulously documenting each stone and object.

This effort paved the way for many other rescue operations in India. The Buddhist site of Devni Mori in Gujarat where the sacred relics were found was another victim of dam construction and is now submerged. Although the edifices at Devni Mori are not relocated, the excavations archived the rich heritage the site offered. Eventually these preliminary investigations and experiments inspired additional rescue efforts to be carried out at locations like the Bagh Caves, where the murals contemporaneous with the Ajanta murals were in danger of disappearing. The paintings were carefully removed from the rock’s surface and preserved.

These few examples of salvaging the past simply serve to highlight the fact that the majority of what we do in archaeology is a sort of salvage archaeology. Archaeological sites are vanishing at a lightning speed as a result of urbanisation, population increase, and the desire for additional land for settlements and agricultural production. Which calls for more rescue operations for hoarding the data that could be lost tomorrow. Salvage archaeology is now more important than ever.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)