With number of customers in the rich world not already online rapidly dwindling, the challenge of tech companies is to find its “Next Billion Users” in lower-income markets.

Ten years ago, only 22 percent (1.5 billion people) of the world’s population could connect to the internet and, of those, only 13 percent in lived in low- and lower-middle-income countries. Today, with almost half of the world online, nearly one in every three people in the developing world has internet access.

Underlying this good news, however, is the more sobering reality that the ability to get online continues to vary across income lines: while over 75 percent of people in the United States and Europe have internet access, only 20 percent in sub-Saharan Africa and 26 percent in South Asia do. The digital divide mirrors inequalities within countries as well, with the poor, elderly, and rurally located less likely to be connected. Women also have less access than men, especially in low-income countries.

The danger is that these already disadvantaged groups will fall even further behind those who participate in digital society. And because many of those who lack internet access live in poor and remote areas, they will be more difficult to reach and less profitable for companies to connect.

Internet use has spread in the developing world in parallel with three broader trends that are changing the digital landscape: the centralization of gatekeeping powers by a few large companies, the assertion of national regulation, and the rapid growth in use the of mobile devices. As online access has expanded globally, the nature of the internet has changed—moving further away from the decentralized ideal that Tim Berners-Lee had in mind when he created the World Wide Web in 1989, to one in which our online experience is increasingly shaped by a handful of large internet companies.

For instance, in the United States, more than 50 cents of every dollar spent on digital advertising goes to Google or Facebook, and more than one of every two dollars spent through online retail goes to Amazon. The same pattern of concentration holds in developing countries: for example, in a recent survey in Kenya, more than half of all mobile traffic was directed through applications owned by Facebook and Google.

At the same time, national governments are increasingly asserting their right to regulate how internet companies operate in their jurisdictions. While national regulations aimed at reining in internet companies are not new, they have become more common and more restrictive. Moreover, a growing number of countries are emulating China’s authoritarian model of the internet, “where technologies of surveillance and identification help ensure social cohesion and security by combating crime, terrorism, extremism, and deviance.”

The other sweeping change is the increased use of mobile devices to connect to the internet. This is particularly true in low-income countries where the rapid uptake of mobile phones has enabled millions of people to connect to the internet for the first time and where the poorest households are more likely to have access to mobile phones than to toilets or clean water.

More than any other companies, Facebook and Google have successfully integrated their products and services across web and mobile applications, contributing to their dominant role in the global market. Today, Google operates domains in roughly 200 countries and territories, and offers services in over 100 languages. Estimates of the company’s market share in online search vary between 82 and 92 percent, and its Android operating system powers more than two billion devices worldwide.

Facebook’s social network also spans the globe, with 2.3 billion monthly active users worldwide and content available in roughly 100 languages. Over 70 percent of Facebook users live in Africa and Asia, and India recently surpassed the United States as the country with the most people on the platform (250 million). WhatsApp, which Facebook acquired in 2014, is the most popular messaging app in the world, boasting more than 1.5 billion monthly active users. Because both companies derive most of their revenue from advertising (ads provide 98 percent of Facebook’s revenue and 85 percent of Google’s), their profitability depends on increasing the number of their users or the revenue they generate from each.

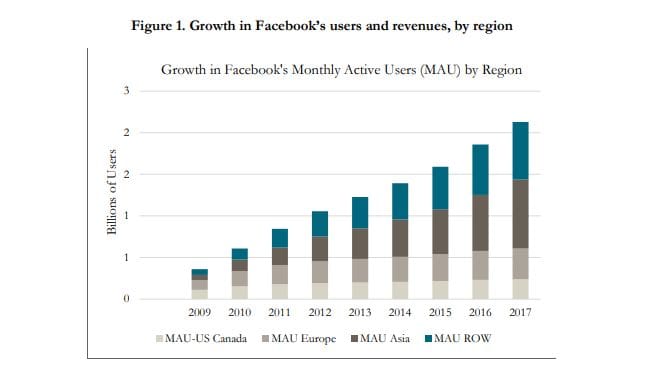

Today, tech companies earn much more from their users in the developed world. For example, Facebook’s average revenue is $26.76 per user in North America, compared to only $1.86 in its “Rest of World” category, which captures users in Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. As a result, Facebook earns roughly 43 percent of its revenue from the United States even though only 10 percent of its customers live there (see figure 1). Google similarly earns about 46 percent of its revenue in the United States.

The industry’s challenge is that the number of potential customers in the rich world not already online is rapidly dwindling. Tech companies have responded to this dynamic by shifting their focus to finding the “Next Billion Users” in lower-income markets.

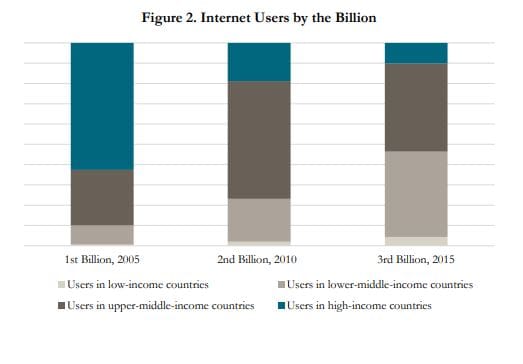

The “Next Billion Users” is a club with shifting membership. Figure 2 captures how the composition of each cohort has changed over time.

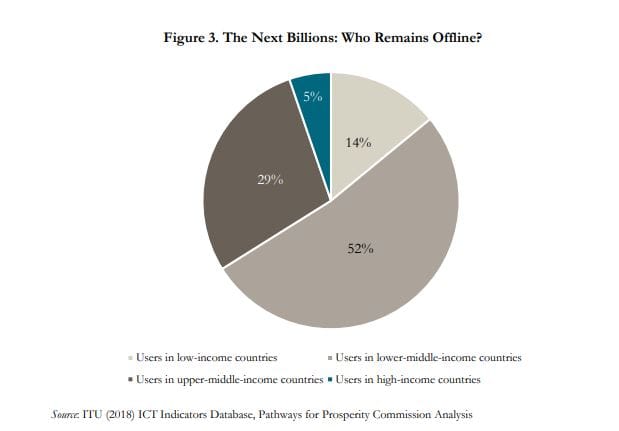

In 2005, when the internet crossed the one billion user threshold, most internet users (62 percent) lived in high-income countries, while less than 10 percent lived in the developing world. The share of new users from developing countries rose to nearly a quarter in the second billion cohort (which took shape between 2006 and 2010) and to 47 percent as the third billion came online from 2010 to 2015. Today, more than 65 percent of the roughly four billion people in the world without internet access lives in countries with a per capita GDP of less than $3,895 a year (i.e., countries classified by the World Bank as lower-middle income and low-income) (see figure 3).

The rapid growth of internet access in the developing world that began earlier this decade coincided with efforts by the world’s largest tech firms to target lower-income markets by expanding the reach of networks and tailoring products to a more difficult operating environment and a different set of user needs. These differences include:

The predominance of mobile

As noted above, most users in the developing world access the internet through a mobile phone rather than a computer. In Kenya, for example, 99 percent of all internet access is through mobile devices. As Google Vice President Caesar Sengupta notes, “most of the next billion users have never used a PC and may never use one. They don’t think of the internet as something you access with a mouse and a keyboard.” Smartphones are also becoming increasingly common. GSMA (Groupe Spéciale Mobile Association), the trade association of mobile network operators, projects that smartphone adoption in developing countries will exceed 60 percent by 2020.

Poor connectivity

Many internet users in the developing world still depend on 2G technology for internet access, even though it was not designed to handle data intensive applications. By 2020, nearly 70 percent of Southern Asia and over percent of Africa will still depend on 2G networks. As a result, connection speeds in the developing world are often dramatically slower than those in high-income countries. For example, it takes more than 25 times longer to download 1 megabyte (the equivalent of one hi-res digital photo download) in Mali or Mauritania as it does in North America.

High cost of data

Internet users in the developing world face a high cost of data relative to their income. The World Bank estimates that paying for a phone and data plan can cost customers in 15 African countries more than 20 percent of their monthly income. By comparison, Norwegians only need to spend 0.27 percent of their monthly income. In addition, while most consumers in high-income countries enter into long-term contracts that provide virtually unlimited data, most people in the developing world purchase credit in advance and draw down their balance as they use data. Together these factors shape how people in the developing world use the internet. Because they pay such a high price to access data and do so “by the bit,” they are keenly aware of the monetary cost associated with every click they make.

This leads to what Jonathan Donner of Caribou Digital has called a “metered mindset” that serves as a “looming, persistent deterrent to surfing, web browsing, and effective use of the internet.

This is an excerpt from Governing Big Tech’s Pursuit of the “Next Billion Users” published by Center for Global Development.

Read the full paper here.