The secret diplomatic coup needed skills that would have shaken the world’s top hotels: Freshly slaughtered sheep had to be made available for the royal guest mid-ocean; efforts to bring the royal harem on board had to be gently foiled; an army of coffee-servers, scullions, slaves and even the court astrologer had to be accommodated; the indiscretions of the younger princes, who hooted and whistled while watching movies starring a scantily clad Lucille Ball, hidden from their fathers.

In February, 1945, as war raged around the world, Saudi king Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud and United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt met on the deck of the USS Quincy in the Suez canal—a summit that ensured the Persian Gulf’s vast oil and gas would for generations be guarded, and controlled, by America.

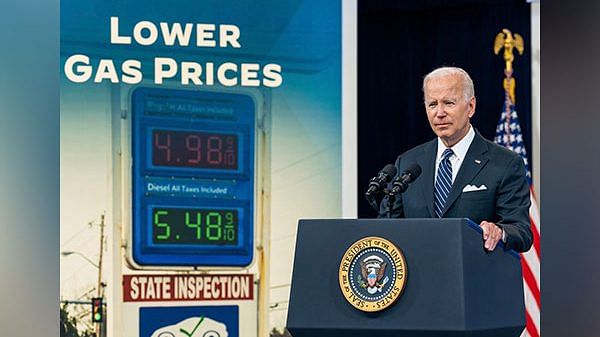

As President Joe Biden prepares to make his first official visit to Saudi Arabia— where he is expected to meet with King Salman Bin Abd’ al-Aziz as well as crown prince Muhammad Bin Salman—India will be carefully watching to see if a new compact can be crafted. Energy prices have spiked since the war in Ukraine, hurting economies around the world.

Enhanced production by Saudi Arabia will help tamp down prices—but for a deal to be made, Biden will have to be prepared for crow to be on the menu at his state dinner in Jeddah. Three years ago, responding to outrage over the assassination of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, then-candidate Biden had vowed to end arms sales to Saudi Arabia, “and make them in fact the pariah that they are.”

The problem, though, is deeper than hurt feelings: It goes to the heart of America’s role as a global power, and ruler of an oil empire.

Also read: Amidst rising crude prices, a strong dollar poses problems

The very special relationship

In the build-up to the summit of 1945, the charismatic Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agent William Eddy had worked hard to cultivate King Abd al-Aziz. Even though no agreement was reached on the contentious issue of Israel, Eddy’s efforts ensured the two leaders bonded. Abd’ al-Aziz was gifted a DC3 transport aircraft, which he reciprocated with a diamond-encrusted dagger, belts of woven gold and embroidered harem dresses—a sly reference, perhaps, to Roosevelt’s not-always-scrupulous commitment to marital fidelity.

As a token of his gratitude, the king even offered one of his sons in marriage to Eddy’s 11-year-old daughter.

This bonhomie was greased by oil. Ever since the discovery of massive Saudi oil deposits in 1938, historian Tyler Priest has written, the centre of gravity of the global hydrocarbon industry shifted to West Asia. Large scale American investments followed. The US had supplied almost 80 per cent of the petroleum needs of its European allies through the Second World War. The lifting of price controls threatened these economies—and enhanced Saudi production helped bring the cost down again.

In 1944, Roosevelt told a British diplomat: “Persian oil is yours. We share the oil of Iraq and Kuwait. As for Saudi Arabian oil, it’s ours.”

The empire of oil didn’t come cheap. In the course of the Second World War, itself, the US had set up bases in Iran, Oman and Saudi Arabia. To these, as the Cold War unfolded, it added facilities in Bahrain, Pakistan, Iraq and North Africa. The scholar John Gaddis has argued, the US didn’t seek an empire—but it ended up with one.

Empires are expensive, though. Arthur Herman estimated, in a 2014 analysis, that “keeping the region’s shipping lanes, including the Strait of Hormuz, open to tanker traffic costs the Pentagon, on average, $50 billion a year—a service that earns us the undying enmity of populations in that region.” The US military, the argument went, were effectively providing security for big Asian oil importers, like China.

There were, some experts argued, less blunt instruments at hand. “Iran,” Herman pointed out, “saw its former stranglehold over Europe’s oil supply collapse as the United States’ tumbling demand for imported oil allowed Europe to buy what it needed from other sources, and at relatively low prices.”

From the middle of the last decade, as shale-drilling technologies propelled the United States towards becoming the world’s biggest oil producer, the expense seemed unjustifiable.

Also read: Buying Russian oil is ruble wise but rupee foolish. It bloodies India’s hands

The Ukraine crisis

The war in Ukraine changed everything. The US responded by imposing sanctions on Russian oil—and that sent prices to record highs. India and China—seeking to protect their vulnerable populations, and correctly noting Europe continued to buy Russia’s natural gas—increased their purchases of discounted oil. Europe announced it would impose sanctions, but stocked up in the meantime. The end result of the sanctions, thus, was a windfall for President Vladimir Putin.

Exports of crude oil from the United States have risen to record levels, but not fast enough to impact prices. In spite of Biden’s calls, American production is still well below 2020 levels. Trying to recoup losses caused by the crash in prices after the pandemic, American producers welcome high prices—and don’t see a reason to produce more.

Last week, the G7 group of industrialised countries considered two alternatives. Led by Italy’s prime minister, Mario Draghi, one proposal calls for a cap to be imposed on global prices, by forming a cartel of big buyers, or imposing secondary sanctions on countries that keep buying Russian.

France is pushing, meanwhile, for Iran and Venezuela—both hit by earlier US sanctions—to be brought back into the oil market. Long-stalled talks between Tehran and Washington on Iran’s nuclear programme resumed this week, but an end to sanctions could be months or years away.

The most easy-to-achieve solution is to persuade Saudi Arabia to open up the valves on its oil pipelines. That will dent its ability to fund the gargantuan projects—among them, improbably, a desert city with a ski-range—that the kingdom says are key to its post-oil future. The kingdoms will want a price—which America needs to decide if it really wants to pay.

Also read: Asia could face higher inflation and slower growth amid soaring oil prices

The line in the desert sand

Last time a crisis threatened to overwhelm Saudi Arabia—in the form of the Iranian Revolution, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan—the US had drawn a thick red line in the desert. “Let our position be absolutely clear,” President Jimmy Carter announced, “An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.”

These weren’t idle worlds: The US has gone to war eighteen times since 1980, seeking to keep West Asian sources and shipping routes secure. In one 2010 paper, the economist Roger Stern estimated the military costs of maintaining the oil empire cost the US $6.8 trillion from 1976 to 2007. “On an annual basis,” Stern recorded, “the Persian Gulf mission now costs about as much as did the Cold War.”

Is the United States still willing to protect its old oil empire? There’s no simple answer. A new generation of young Americans, conditioned by the bitter experiences of the second Iraq war and Afghanistan, is deeply sceptical of overseas military commitments. There’s also the prospect that a future US administration might think endless war in Ukraine isn’t worth the while—or that President Putin throws in the towel.

Like many world capitals, New Delhi will be anxiously watching the summit in Saudi Arabia—knowing its fate is tied to the decisions the king and the president will make.

The author is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)