Like From Russia With Love, perhaps the intelligence officer thought: The story of the improbably good-looking Kashmiri prisoner belonged in a movie. “Found to possess a highly romantic disposition,” the prisoner’s dossier later recorded, “and was carrying on with three different girls. His taste in girls was fairly cosmopolitan, in as much as one of these girls was Muslim, the other Hindu and the third Buddhist. His tastes were expensive, and his living extravagant. With all these traits in his character, it was perhaps inevitable that he should ultimately find himself in the twilight world of espionage.”

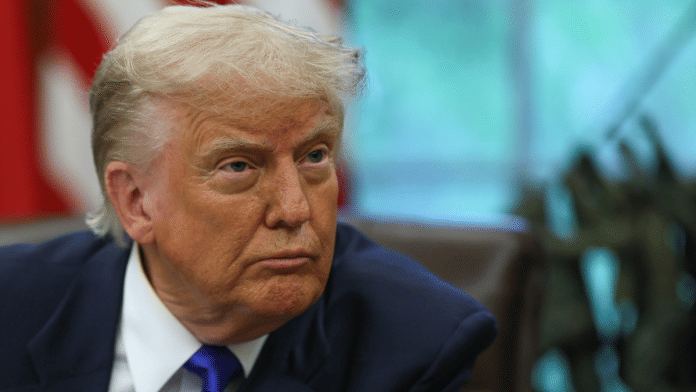

Last week, as he announced a ceasefire in the savage skirmish between India and Pakistan, US President Donald Trump vowed to work “to see if, after a thousand years, a solution can be arrived at.” Even though most dismissed the idea as a meaningless Trumpian thought bubble, the words weren’t casual. For generations, it’s largely forgotten that American presidents have sought to forge India-Pakistan peace and make both countries allies in the containment of the People’s Republic of China.

The most thoroughgoing American effort to mediate peace, which ran from 1961 to 1965, set a bizarre set of characters into motion: The flamboyant playboy-spy Mian Ghulam Sarwar, his team of highly-trained covert operatives, the Pakistan intelligence services, Generals, and diplomats from India and Pakistan, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Like a nuclear chain reaction, these elements would gather immense energy, eventually triggering a full-scale war. For India, Pakistan, and Trump himself, the story should provide a reason for caution.

A fool’s errand

Led by its representative at the United Nations, Philip Noel-Baker, the UK threw its weight behind Pakistan in the negotiations that followed the 1947-1948 war. To the UK, Pakistan seemed a critical ally to protect against the southward advance of Soviet communism. To this end, Noel-Baker sought to build a great power consensus around allowing Pakistan to continue pumping state-backed irregulars into Kashmir, installing a new administration, and holding a plebiscite under United Nations authority.

George Catlett Marshall, then-US secretary of state, recognised the biases in Noel-Baker’s proposals and pushed back. The US, however, conceded the UK’s primacy in the affairs of its former colonies. The United Nations Security Council resolution adopted on 21 April 1948 didn’t go as far as Noel-Baker sought but was distinctly tilted toward Pakistan.

Then, in 1950, the United Nations representative on Kashmir, Owen Dixon, proposed handing over the Muslim-majority parts of the region to Pakistan. The proposals were rejected by both India and Pakistan for different reasons. The pressure on India to accept the UK-led proposals continued to grow, however.

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, historian Navnita Chadha Behera records, now decided to dig his heels in and “not give an inch. He would hold his ground even if Kashmir, India and the whole world went to pieces.”

From 1948 to 1957, the Security Council debated the Kashmir dispute 18 times, but was unable to persuade the two countries to reach a settlement. The UK got the ceasefire it wanted, ensuring India would not push east and go to war again. Like other would-be mediators, though, they would learn peacemaking in Kashmir was a fool’s errand.

Late in 1958, though, Field Marshal Ayub Khan staged a coup d’etat in Pakistan, banned all political activity in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and smugly proclaimed: “The biggest weapon of a politician is his tongue, which we’ve controlled. I think things are going to be quiet for a while.”

From declassified diplomatic cables, it’s clear that India was somewhat less enthusiastic about the coup, fearing that the hawkish statements by Field Marshal Khan were a warning of war. “An Indian General who knew Ayub in the pre-Partition army commented that Ayub is inclined to take precipitate action without thinking of consequences,” the cable records.

To the UK and the US, the rise of martial law seemed an opportunity. Finally, there was an authoritarian ruler who could brush aside political objections to a compromise on Kashmir.

Also read: Trump is wrong about Operation Sindoor. Not an ancient battle, it’s a war on terror

Toward talks

Ever since the autumn of 1961, Central Intelligence Agency officer-turned-diplomat Robert Komer had floated ideas for an India-Pakistan bargain on Kashmir: a common air-defence system, a customs union, and even joint management of agriculture in Punjab might do the trick, he hoped. Perhaps New Delhi could be persuaded to give up “a little more wasteland up in Ladakh” and some minor territorial concessions along the ceasefire line of 1948. Perhaps, who knew, there could even be “joint tenancy” in the Kashmir Valley.

There was little attention paid to Komer’s ideas, until 1962 when the China-India war drew the US into the region. America began providing military assistance to a desperate India. Late in 1962, Duncan Sandys, the United Kingdom’s Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations, and Averell Harriman, the United States’ Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs, were dispatched to discuss long-term military cooperation.

Even though India was determined to concede nothing, the need for Western arms brought massive pressure to bear. Indian foreign minister Swaran Singh and his Pakistani counterpart Zulfikar Ali Bhutto finally made their way to the negotiation table in 1962.

From the beginning, the talks got off to a bad start. A day before negotiations began, Pakistan made an agreement on demarcating its borders with China, which would end in the handing over of parts of Kashmir. Even then, six desultory rounds of dialogue took place between 27 December 1962 and 16 May 1963. India proposed drawing a border that would give Pakistan the entire occupied area west and north of the Kashmir Valley. Islamabad, however, was willing to grant only a sliver of territory in Jammu.

Also read: Tense, bruised, but unbeaten Jammu. Peace in Kashmir isn’t about ceasefires or ceremonies

Lurching into war

To Komer, declassified documents show, it became clear that US’ pressure on India was having perverse outcomes. “I wonder if we aren’t doing ourselves a disservice by our continued pressure on Kashmir,” he wrote in a 14 May 1963 note. In another, 22 October 1963 memorandum, he noted the Pakistanis “appear to be deliberately building up tensions over Kashmir”. Komer believed that talk of Indian concessions on Kashmir were engendering “a dangerous Pak emotional reaction”. “The longer we nurture Pak illusions,” Komer told then-US president John F Kennedy, “the more a head of steam is built up in Pakistan, and the harder such a reaction will be to head off”.

Komer proved prescient. The memoirs of Lieutenant-General Gul Hassan Khan, the last commander-in-chief of the Pakistan Army, reveal that he authorised “intensification of the firecracker type of activity that was already current”, a reference to terrorism. The Pakistan Army was to train guerrillas like Mian Ghulam Sarwar, who would be tasked with “arming the locals and helping them rise against the Indian Army of occupation”.

Then, on 29 August 1965, Pakistan’s army chief General Muhammad Musa received secret orders to initiate a full-scale war. “As a general rule,” the orders read, “Hindu morale would not stand for more than a couple of hard blows delivered at the right place and the right time”.

War fell over Kashmir like fresh snowfall. Mian Ghulam Sarwar’s secret cells tore up the leaves of the Quran and scattered them around the Roza Bal ziarat in Srinagar in an effort to spark an insurrection. In the small village of Wutligam, a woman charged with promiscuity had been marched to the village square and then shot through the back of her head. In Arigam, jihadists looted a grocery store owned by a Hindu, Raj Nath; in Arizal, they tried to assassinate the pro-India politician Ghulam Qadir.

Kennedy’s mediation effort had led Pakistan to sharpen its sword, not beat them into ploughshares. Failure became a pattern. Bill Clinton’s offer to mediate Kashmir in 2000 laid the path for the 2001-2002 showdown. Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign promise to mediate Kashmir similarly emboldened a pattern of escalated support for jihadists that culminated in 26/11. True, India shares the blame.

Trump’s Kashmir fixation is no casual impulse. He aims to succeed, as in so many other things, where Kennedy and Obama failed. In 2020, Trump outraged India’s foreign policy establishment by asserting that Prime Minister Narendra Modi had asked him to mediate on the Kashmir conflict, and then brushed off New Delhi’s denial, repeating his claim. For this, India shares the blame. In 1999, 2001-2002, and again in 2019 and 2025, it invited superpower intervention after unleashing a military crisis it proved unable to control.

Likely, history shows us, dangers lie ahead. India must begin preparing now for the price it may have to pay for this self-inflicted foreign peacemaking.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. His X handle is @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)

It is not Trumps fixation. He is crude to let the proverbial cat out of the bag. Pakistan surrendered itself to the American interests decades back. It has since then resigned to a gold digger status which was also mentioned in this daily a few days back. Pakistan holds substantial geographical significance too. It is merely a totem to balance the Asian power equation and the usual player is America. Americans will never stop playing these games because of their inherent desire to be the boss of the world. We should be least concerned with what America thinks. If there is something that Operation Sindoor showed, it is that India too can break its shackles and display much higher strategic autonomy than is perceived by the opinion pieces in different dailies across the world. One should never forget the civilisation prowess of India. It should be taken into consideration because the bigger powers of today are wary of one thing – rise of another power axis in the world. And the West hates it to see it again in Asia.

No balls to print comments that call you out for the disgrace that you are huh? Pathetic

Mt praveen swamy is I’ll suited for writing to sn indian publication. His thoughts and offerings are more suitable to be printed in The Dawn. Perpetually pessimistic about India, or maybe the current government, we don’t hear one note of positivity from him on anything Indian. He invites “foreign” guests on his talk show to achieve the same objective, run down India and its actions. wheb young Indians are full of hope for their future, comes this old pessimistic uncle who cannot say one thing positive about India. The Print should think twice before having these columnists on their payroll. I am tempted to subscribe but then this joker and the lady joker Sagarika make me throw up at the prospect of paying anything to ThePrint

Did india invite superpower intervention in 2019 or 2025, does the author have proof? Further, whatever he has written in this article is called whataboutry guised in hindsight bias…

In 1999, 2001-2002, and again in 2019 and 2025, it invited superpower intervention after unleashing a military crisis it proved unable to control.

Mr swamy, please cross the border and write for The Dawn, or other pak leaning outlets. If you have good reasons to believe the above statement please publish them. Otherwise do us a favour and get the hell out of this country.

President Trump is a realist. Although the entire world sticks to the formulation, Kashmir is a disputed territory whose future should be settled by a peaceful dialogue between India and Pakistan, and in accordance with the wishes of the Kashmiri people, as a practical matter, they accept the status quo, with the LoC sacrosanct. What worries the international community, at some stage could also weigh on investor sentiment, is the possibility of war between the two countries. How this should be done is beyond my pay grade, but India and Pakistan have to work diligently to reduce the possible of a potentially nuclear conflict to much below where it now is. The recent IMF decision on providing $ 2.4 billion to Pakistan is a reminder that we are not able to bring the world entirely to our point of view.

First, we ourselves should stop talking about Pakistan. Pakistan managed to garner headlines in the last 3 weeks, out of nowhere.

We were all discussing something else. And now we are discussing something else.