Twenty million people—soldiers assigned to Nazi death squads, residents of bourgeois Berlin neighbourhoods, and every second adult living in the Third Reich—had lined up to watch the movie. The onscreen drama went like this: Lacking the money to buy his wife coronation jewels, the Duke of Württemberg turns to the unscrupulous financier, Joseph Süß Oppenheimer. The evil Jew corrupts the Duke. Later, he rapes the innocent Dorothea Sturm as the price of her husband’s freedom from prison. Following her suicide, Süß is executed by the townspeople. The Jews are expelled from Württemberg.

“Finally, an anti-Semitic film,” Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels happily recorded in his diary entry for 18 August 1940. The returns on the regime’s two million reichsmarks were impressive: After special screenings of Jud Süß in Auschwitz, historian Susan Tegel records, prison guards would be inspired to give Jewish prisoners extra beatings.

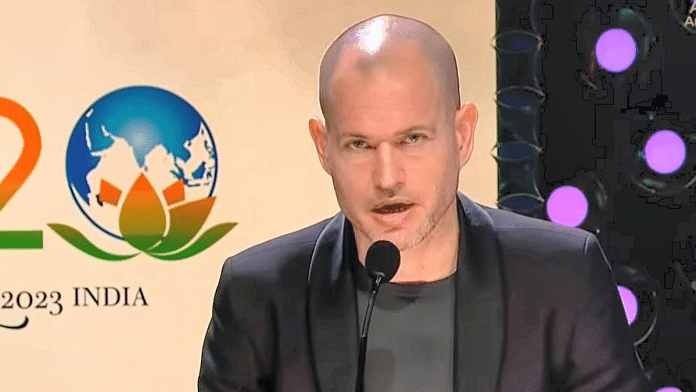

Earlier this week, Israeli filmmaker Nadav Lapid provoked a furore by describing Vivek Agnihotri’s The Kashmir Files (2022) as “a propaganda, vulgar movie, inappropriate for an artistic competitive section of such a prestigious film festival”. Facing a deluge of social media invective—some of it ugly anti-Semitic abuse—Israeli diplomats have pushed back against Lapid’s remarks.

Fictions are not innocent. Like all narratives, The Kashmir Files makes choices about which truths to tell and how to tell them, censoring inconvenient history. Even though its tenor is inflammatory, the film isn’t a call to genocide. And while India’s movie industry is regulated through a censorship regime more familiar to totalitarianism than liberal democracies, it has a rich tradition of talking back to power.

Lapid’s critique, though, raises issues that are bigger than one film. To what extent has the popular film in India—and other mass media—served as an instrument of State power? And how does power impact our imagination? The use of films by totalitarianism systems is a useful prism to reflect on these complex questions and their impact on our society.

The Nazi illusion industry

Films in the Third Reich weren’t just a production line for hate. Nine out of every 10 of the 1,100-odd produced between 1933 and 1945 were non-political comedies, detective stories, and melodramas. Nazi propagandists understood that cinema audiences sought to immerse themselves in familiar fantasies, not demagoguery. The social historian Richard Grunberger has observed that had a cinema-goer “dozed off in the Depression and woken in the Third Reich, he would have found the screen filled with the self-same images”.

“Films in the Third Reich emanated from a Ministry of Illusion,” critic Eric Rentschler has written, “not a Ministry of Fear…If one is looking for sinister heavies garbed in SS black or crowds of fanatics saluting their Führer, one does best to turn to Hollywood films of the 1940s.”

The elements of Nazi control of films—among them censorship as limitations on American imports—were initiated under the liberal-democratic Weimar Republic. The Nazis would expand on these powers, undoing safeguards that mandated no film could be banned just because of its political content.

Early in its life, the Third Reich grasped that the industrialised production of illusion gave it great power. Through the State-controlled conglomerate Universum Film-Aktien, scholar John Altman noted as early as 1948, the Nazis worked to shape the zeitgeist of a restless post-First World War youth cohort. This cohort—“aimless, pseudo-romantic, sceptical, cynical”—was among the central audiences for the Nazi message. From 1934 onward, ‘Film Hour’ became a feature of German school education.

Karl Ritter’s A Pass on a Promise (1938)—in which a young soldier breaks up with his Left-wing girlfriend and chooses the “real comradeship of fighting men”—was typical of this genre. Film Hour would lead thousands of teenagers to fight—and die—for their Führer.

Even ostensibly apolitical films, critic Scott Spector notes, could be redolent with ideology. La Habanera (1937) has Zarah Leander seduced by the tyrannical matador Don Pedro—again played by Jud Süß star Ferdinand Marian. Leander discovers that the seduction of the passionate south is short-lived and longs to return to her Nordic roots. Luis Trenker’s The Prodigal Son (1934) tells the story of a Bavarian mountain youth’s disastrous adventure in New York, after which he discovers the value of his roots.

The audience, of course, sometimes subverted the message: As Marcia Klotz observes, Jud Süß ended up creating a strangely sexy villain. Ferdinand Marian—relentless pillager of Aryan womanhood—would “receive baskets of love letters from every city in Germany”.

Also read: Left and liberals have crafted a delusory narrative of inevitable Muslim genocide in India

Manufacturing consensus

For the most part, though, the Nazi film industry succeeded—and it was not alone. Following the Soviet revolution, filmmakers enjoyed considerable freedom for over five years. Lavish costume dramas like The Decembrists, the political satire of filmmakers like Iakov Protzanov, and new avant-garde directors like Sergei Eisenstein competed. Foreign films were widely available: Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks received an ecstatic reception on the streets of Moscow.

Then came the rise of Joseph Stalin—and a new kind of disciplined Soviet film. Filmmakers were called on to eradicate the individual and their inner lives: The focus was, instead, to be the State and its relationship with the people.

Film theatres began showing movies like Tanka, The Bar Girl (the story of a Kulak who plots to murder the Communist schoolteacher, Sestrin, to ensure the villagers remain addled to alcohol). In the end, Denise Youngblood writes, Sestrin rescues Tanka from the clutches of the Kulak and turns the tavern into a tea house. The workers lived happily ever after without vodka.

The People’s Republic of China also found film a powerful medium to take its message to rural regions—often areas without electricity or theatres. The New Story of an Old Soldier (1959) tells of an effort to set up a State farm, which succeeded because the hero “mobilised the people and relied on the leadership of the Party”. The dialogue, Hsiung Deh-Ta wrote, was crude—“Don’t thank me, thank the Party”—but the film itself proved popular.

Also read: Kejriwal gave BJP a ‘thug life’ response on Kashmir Files row — a template to counter hate

Facing unfreedom

Liberal democracies had, since early in the last century, struggled with the seditious potential of films. The United States Supreme Court, in 1917, ruled that films did not enjoy the right to free speech. Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) agents harried Charlie Chaplin, convinced he was a Communist agitator. From 1942 to 1945, Clayton Koppes reveals, the office of war information arm-twisted prominent American studios into ideological collaboration, an arrangement that would stretch throughout the Cold War.

In the long term, the impacts of these arrangements were limited: Big studios leveraged their economic and political reach to ensure the industry was able to self-regulate. From the 1950s, filmmakers won a succession of judgments protecting their freedom of speech—even to make films purported to be pornographic or blasphemous.

Independent India took a very different course: “Too much melodrama,” Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru chided filmmakers in 1952, “takes away the drama of life.” Élites in post-colonial India, Aruna Vasudev has observed, saw films as a “reprehensible, though unavoidable, social catastrophe.” “Film has become a powerful influence in people’s lives,” Nehru grudgingly conceded. “Films, which are just sensational or melodramatic… will not be encouraged.”

Legalisation introducing film censorship in 1952—drawing on colonial-era practices—tightened the space for democratic expression, placing pressure on filmmakers to centre their work on social pieties.

For much of the 1950s, filmmakers were enthused by Nehru’s dreams. Film scholar Priya Joshi has noted, however, that commitment began to fray across the first decades of Independence. The schisms lay wide open in Amar Kumar’s Ab Dilli Dur Nahin (1957), in which a 10-year-old travels to the capital to petition the prime minister against the wrongful conviction of his father. Nehru had promised to meet the boy in the last scene—but was eventually recorded only to have given spectral appearances in rallies and posters.

The film bureaucracy responded to Nehru’s diminishing capital by clamping down. Dilip Kumar’s 1961 film Ganga Jamuna was also threatened with a ban for violence and vulgarity, a decision only overturned after the Prime Minister’s intervention.

Indira Gandhi used popular films — Kaala Patthar (1979) was one — to legitimise her policies like coal nationalisation. From then on, Soutik Biswas writes, an ever-growing number of films have been banned, essentially making it impossible to traverse contentious subjects like religion, sexuality, or political conflict.

Films valorising Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s policies or the ideology he represents have exploded in volume. His opponents in states like Tamil Nadu are using the same tools to build rival cults. They are united in their commitment to crushing genuine dissent.

Like the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany collapsed because its culture industry left its people unable to even conceive of the questions they needed to be asking themselves. Lapid has dryly noted that nationalism can blind an individual: “You love your country so much, you are convinced that everyone needs to love it.” “Look,” the filmmaker went on, “I’m Israeli and I can hate Israel, say terrible things about it, and curse it without end.”

Free societies have the confidence to hear harsh words—and the integrity to ask if they might be true.

The author is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)