To begin with: Dawood Ibrahim Kaskar must die, and the last coffin nail be hammered down, or nothing can come of his story. Charles Dickens, who knew the art of storytelling, wrote: “If we were not perfectly convinced that Hamlet’s father died before the play began, there would be nothing more remarkable in his taking a stroll at night, in an Easterly wind, upon his own ramparts than there would be in any other gentleman rashly turning out after dark in a breezy spot.”

Three decades ago, 12 bombs tore through the heart of Bombay, killing 257 people and injuring over 1,400. Even today, it remains the most lethal terrorist attack on Indian soil, far larger than 26/11 or 7/7 or the host of apostrophised dates with which we have become depressingly familiar. The bombings were vengeance, a judicial commission found, for a police-backed massacre against the city’s Muslims.

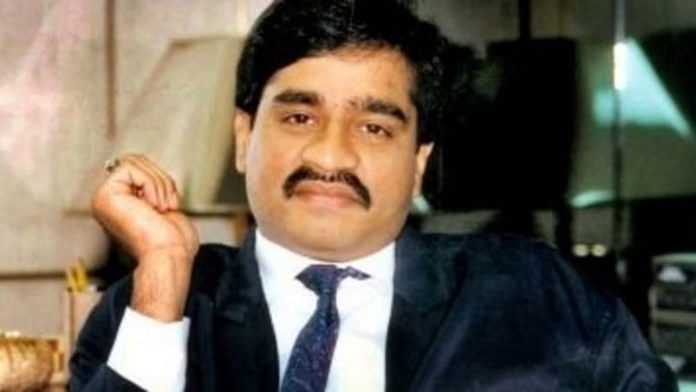

From government records, we know the mafioso who ordered the bombings will turn 68 on Boxing Day, 26 December. There is no sure way to know where, how, or even if, he is alive.

The only journalist ever to report on his life in Karachi, Newsline’s Ghulam Hassnain, found he lived well, in “a palatial house spread over 6,000 square yards, boasting a pool, tennis courts, snooker room and a private, hi-tech gym.” “He wears designer clothes, drives top-of-the-line Mercedes and luxurious four-wheel drives, sports a half-a-million rupee Patek Phillipe wristwatch, and showers money on starlets and prostitutes,” he wrote.

Finishing Dawood’s story has become a kind of pathology in India’s media, with imagination serving to deliver closure to an unbearably painful but open-ended tale. Last week, a shower of fake-news tweets assured us he had been poisoned; in 2017, he was rumoured to be claimed by a brain tumour or cardiac problems; in 2016, his gangrenous legs were said to have been amputated. His life was claimed by Covid in some reports and by assassins in others.

In 2014, when Narendra Modi stood on the cusp of being elected prime minister, he vowed to hunt down Dawood. That promise hasn’t been delivered on—but some in the Indian media seem determined to proclaim success, regardless.

Also read: Stop fussing over ‘Khalistani’ targets. Is it beyond us to get real Pakistani terrorists?

Killing the don

Since 2005 at least, it has been known that elements of the Indian intelligence services have been seeking to facilitate Dawood’s last journey from his home to the grave. That summer on 11 July, the Mumbai Police arrested Vicky Malhotra, a gangster long sought for murder, extortion, and arms smuggling. Malhotra was a key figure in the networks of Rajendra Nikalje, a Dawood lieutenant-turned-bitter enemy currently held in Tihar Jail.

The Mumbai Police, we know from the memoirs of senior police officer Meeran Chadha Borwankar, had been intercepting Malhotra’s phone calls, listening as he arranged a meeting with a man he called “sir”. The man, when held along with Malhotra, identified himself as the just-retired director of the Intelligence Bureau and National Security Advisor since 2014, Ajit Doval.

Even though Doval denied having been present with Malhotra, this account of events figured in declassified United States diplomatic cables as well as multiple media accounts. Former Home Secretary RK Singh later alleged that the Mumbai Police had destroyed a covert operation to kill Dawood, authorised by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. The operation, he claimed, had been led by Doval.

Later media reports suggested that multiple gangworld figures, including Ejaz Lakdawala and Ravi Pujari, might have been hired for similar enterprises. On one occasion, the group came close to ambushing Dawood at a dargah he regularly visited but was defeated by the security arrangements.

Indian anger was, in part, driven by Dawood’s increasingly brazen presence in Pakistan. Dawood’s eldest daughter, Mahrukh, had married cricket star Javed Miandad’s son, Junaid, at a lavish ceremony in Karachi. Pakistan’s intelligence services were treating Dawood like a national treasure. Later, former military ruler General Pervez Musharraf said many in Pakistan thought Dawood had “done a good job” by retaliating against the communal riots.

Former Research and Analysis Wing officer Vappala Balachandran, among others, counselled that the practice of using “patriotic gangsters” as agents of national security aims was a high-risk strategy. The price criminals working for organisations like the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) paid in drug-running and terrorism—defeating the ends sought.

As Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate continued to step up strikes against targets in India, though, these voices fell on deaf ears. Following a suicide attack on the Indian Embassy in Kabul, then-National Security Advisor MK Narayanan told journalists: “Talk-talk is better than fight-fight but it hasn’t worked.”

In an essay in The Indian Police Journal in 2012, Doval pointed to the growth of covert action—“a low-cost sustainable offensive with high deniability, aimed to bleed the enemy to submission”—across the world. He noted that other countries had been “promoting terrorism and insurgencies, political assassinations, social disruption, sabotage, subversion etc.” India, he suggested, needed the same tools in its arsenal.

The deep scars left on India by the 1993 bombings made Dawood a prized target and it seems reasonable to speculate the campaign to kill him continued.

Also read: Afghan, Pakistan cartels survived empires. Now they are drowning Indian Ocean region in drugs

The disappearance of Dawood

The last man who we know for a fact met Dawood was ThePrint’s editor-in-chief Shekhar Gupta, back in 1993 on the eve of the gangster’s departure for safe harbour in Karachi. Dawood, Gupta recounts, had promised him an interview. Though he met Gupta at the terrorist’s office in Pearl Building in Dubai, “decorated with gold-inlaid paintings of Ajmer Sharif and Quranic verses,” he declined to speak on record. There was even a parting threat if news of his presence in Dubai was to be published.

Later, under pressure from the multinational Financial Action Task Force (FATF), Pakistan publicly listed Dawood’s properties in Karachi—‘White House’, near Saudi Mosque in the Clifton neighbourhood, House Number 37 on 30th street in the upmarket Defence Housing Authority, and “a palatial bungalow” in Noorabad.

Hassnain described Dawood’s everyday life as “kingly”. “He wakes in the afternoon,” Hasnain claimed. “After a swim and shower, he has breakfast. In the late afternoon, he gives his employees an audience. As the sun sets, Dawood and his party set off for any one of his ‘safe houses’ in Karachi for an evening of revelry—usually comprising drinks (Black Label is his preference), mujras, and gambling. The long-married Dawood’s passion for women has made him a favoured client for local pimps.”

Evidence available from international investigations suggests Dawood expanded his business. Lieutenants like Munaf Halari helped Dawood expand his businesses in East Africa, the Gujarat Police has said. Ethnic Asians—with ties of kinship and trade to Karachi, and often involved in smuggling gold or consumer electronics—provided the backbone for this expansion, scholar Simone Haysom records. The Akasha and Tahir Sheikh Said family in Kenya, Ali Khatib Haji Hassan in Tanzania, Gulam Rassul Moti, and Mommade Rassul in Mozambique: Little empires of drugs mushroomed across the East Africa coast.

Karachi businessman Jabir ‘Motiwala’ Siddiq, who narrowly evaded extradition to the US, is believed to have been one of several figures who laundered Dawood cartel funds through the Karachi Stock Exchange. The wealth was generously shared with senior Generals by the ganglord, enabling their families to educate sons abroad and set up businesses. In essence, Dawood purchased impunity.

“I know what a ghost is,” Salman Rushdie famously observed in his masterwork The Satanic Verse. “Unfinished business, that’s what.” As a memory, Dawood represents some of the darkest recesses of India’s memories: The country’s vulnerability to terrorism, its inability to punish perpetrators, and, most importantly, the savage communal killing that has been entwined with the story of Islamist violence.

This story cannot end with those questions. It needs a full stop, real or imagined.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)