Even as the apocalypse erupted inside the darkness of the shafts near a shed called the Prayer Hall, some hoped the primal energy would end the age of war. “Weapons of peace,” Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee would call the nuclear bombs detonated at Pokhran in the summer of 1998. Less than six months later, though, Pakistani troops had occupied the heights of Kargil, confident India would not respond with full-scale war. Terrorist violence surged, ending with India and Pakistan mobilising their armies in 2001.

Far from ending the danger from neighbours who had already unleashed four wars and two murderous insurgencies, scholar Ramesh Thakur noted, Pokhran opened the door to a new era of “lasting insecurities”.

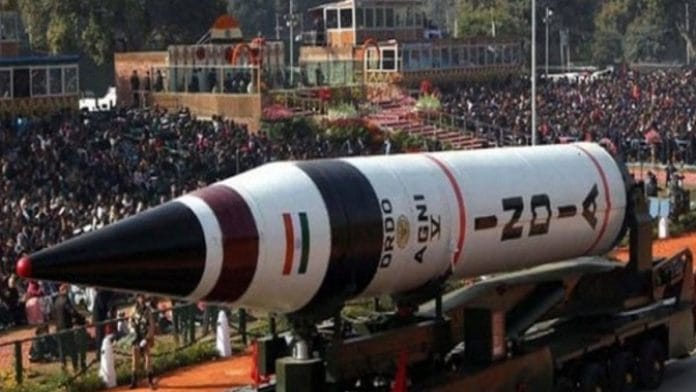

Earlier this week, India tested its first long-range Agni-5, equipped with multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicles, or MIRVs. In essence, these are small nuclear warheads that can be released from a single missile at different speeds and in different directions. The technology has been developed to overwhelm Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) defences and optimise the use of expensive long-range missiles.

This technological achievement is part of the long march India’s nuclear deterrence capabilities have made since 1988. But as strategic weapons experts Hans Kristensen and Matt Korda note, it also opens the door to new perils. The introduction of MIRVs during the Cold War forced both superpowers to develop enormous stockpiles of warheads, threatening the mutual deterrence that kept them from war.

MIRVing the Cold War

Even at the dawn of the MIRV age, questions were raised about the strategic rationale of the technology. In 1976, Lawrence Livermore Laboratory scientist Daniel Rucchonet produced a classified history that sought to understand the Soviet decision-making driving its acquisition of MIRVs by re-examining the United States’ own trajectory. The US and China, the document noted, did not possess extensive ABM defences—raising questions about why the Soviet Union thought it necessary to obtain MIRVs.

From early in the Cold War, scientists in both the US and USSR had begun considering how to protect themselves from intercontinental ballistic missiles. In 1962-1963, the Soviet Union began constructing an ABM system to protect Moscow, which envisaged firing nuclear-armed Galosh interceptor missiles at incoming warheads. Each Galosh warhead had a yield of several megatons, hundreds of times the size of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945.

Like the similar Safeguard system in the US, though, the Soviet ABM system suffered from several major limitations. The Doghouse—the giant radar responsible for tracking incoming missiles—could be deceived by countermeasures like chaff. The radar could also be blinded by nuclear explosions, including the detonation of the Galosh itself. And it could deal with only six to eight incoming missiles, far too small a number by 1962.

To planners in the US, the rise of ABM systems made equipping its arsenal with MIRVs attractive. Arming each missile with multiple warheads would make it easier to overwhelm the interceptors.

MIRVs were also quite cheap. Former Ford Motors president Robert McNamara, who became the US defence secretary in 1961, demanded economic efficiency. A warhead was one-sixth the cost of a missile.

Even though these arguments were attractive, they didn’t impress everyone. The US Air Force argued, for example, that the smaller warheads in MIRV-ed missiles would be ineffective against hardened targets. Though some in the strategic community perceived that MIRVs would deter the Soviet Union from pursuing its ABM programme, others anticipated that the likely response would also produce more warheads.

From 1967, strategic affairs expert Silky Kaur records, the number of warheads in the US arsenal surged, with individual missiles like the Peacekeeper MX carrying 10 each. The US’ land-based intercontinental ballistic missile force, in 1990, was reported to be made up of 2,450 warheads on 1,000 missiles, and its submarine force of 5,216 warheads on around 600 missiles.

The superpowers ended up signing the ABM Treaty in 1972, which led both sides to commit to the protection of just one site with no more than 100 interceptor missiles. In 2002, though, the US withdrew from the treaty to pursue its sophisticated ABM programme. The decision, however, spurred Russia and China to begin the development of increasingly sophisticated missiles, designed to punch through ABM defences and expand the size of their arsenals.

Exactly as scholars like William Potter had predicted decades earlier, the rising tide of MIRVs ended up undermining strategic stability—the ability of the superpowers to ensure mutually assured destruction, which deterred either from going to war. Technologists, he predicted, would “probably come up with more complex, more expensive, and more volatile defences” against MIRVs. The result, put simply, would be a pointless arms race.

The US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had argued against a ban on MIRVs in 1969. “I would say in retrospect,” he ruefully admitted five years later, “that I wish I had thought through the implications of a MIRVed world more thoughtfully in 1969 and 1970 than I did.”

Also read: India must legalise contract soldiers recruited to fight foreign wars. Agniveers are coming

India’s MIRV trajectory

Little imagination is needed to understand the context that has driven India’s pursuit of MIRVs. Even though China does not have significant ABM capabilities yet, it has conducted several successful tests of ballistic missile interceptors since 2010. It remains unclear how much progress China has made on other elements of a deployable ABM system, like space-based early warning satellites and high-resolution tracking radar. However, China’s relentless pursuit of ABM technology since the mid-1980s constitutes a threat to India’s deterrent posture.

Together with MIRVs, the use of decoy warheads, manoeuvring warheads and stealth technologies all offer means to ensure India’s strategic deterrent against China remains robust while keeping costs manageable.

In a thoughtful essay, scholars Rajesh Basrur and Jaganath Sankaran note that the case for Indian MIRVs is not as self-evident as it might seem, though. For one, they argue, it is improbable China would be able to overwhelm India’s military in a future war, or pose an existential threat to the country. That means the risk of nuclear war is relatively low. India’s strategic establishment, they suggest, needs to carefully think through what kinds of deterrent capability it needs, rather than draw on Cold War nuclear theology.

For China, too, there are serious questions to be answered. The country resisted introducing multiple warheads to its DongFeng-5 missiles for over two decades, nuclear weapons scholar Jeffrey Lewis records. Finally, amid rising strategic tensions, China announced it had mated its DongFeng-5 missiles with multiple warheads in 2015. The decision was linked to worries over the US’ increasingly sophisticated ABM capabilities.

Little reason exists, though, to think MIRVs will give China—or India—the strategic security they crave. “In the past, increased nuclear capabilities through MIRVing resulted in an accelerated arms competition, rather than increased confidence in deterrence,” Basrur and Jagannathan observe. The accumulation of warheads by their adversaries will make it ever more tempting for leaders in both countries to reach for the nuclear trigger first.

Also read: Putin’s neo-Gulags are tools of political terror. Navalny death reveals Russia’s tyrannical past

The bomb and the politicians

Like the men who fought the Cold War, successive Prime Ministers of India and Pakistan have stood on the edge of war several times since 1998 but shied away from the prospect of mutual annihilation. “There is an enormous gulf,” former US National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy wrote in 1967 “between what political leaders really think about nuclear weapons and what is assumed in complex calculations of relative ‘advantage’ in simulated strategic warfare.”

Bundy also went on to say that “in the real world of real political leaders—whether here or in the Soviet Union—a decision that would bring even one hydrogen bomb on one city of one’s own country would be recognised in advance as a catastrophic blunder.” Ten bombs on ten cities would be a disaster beyond history, he added.

Locked in a three-way strategic competition, China, India and Pakistan are already in the middle of a landscape far more complex than the one that confronted the superpowers during the Cold War. Fuelling instability is the new Cold War looming between the US and China. The outcomes of this four-way blindfold chess match are impossible to predict.

“Too late” is the cruellest phrase in the English language. Learning from Kissinger in 1969, or Vajpayee in 1998, leaders need to carefully consider the price of the slightest misjudgement that could prove to be catastrophic.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. He tweets with @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)