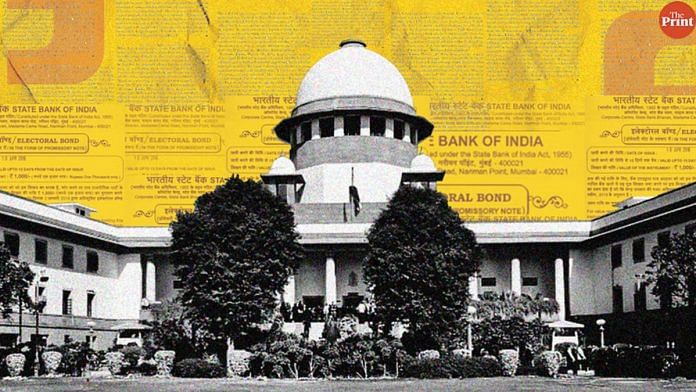

On 15 February 2024, in an extremely significant ruling, the Supreme Court of India declared that the Electoral Bonds Scheme notified in 2018 was unconstitutional. While the majority of the judgment has been authored by Chief Justice DY Chandrachud – joined by Justices BR Gavai, JB Pardiwala and Manoj Misra – Justice Sanjiv Khanna has authored a separate concurring opinion, differing in his reasoning on certain points.

Over the last six to seven years, one of the lingering criticisms against the Supreme Court has been the leisure with which time-sensitive issues of considerable constitutional importance were delayed. And on the top of any such list of cases by any concerned citizen was the EBS case. Hopes that the matter would be disposed of before the 2019 Lok Sabha elections proved to be illusory.

On 12 April 2019, the court refused to stay the implementation of the EBS and merely ordered the political parties to submit in ‘sealed covers’ the details of funds received via EBS to the Election Commission of India. The consequence of the refusal in 2019 has been the funnelling of more than Rs 13,000 crore (from March 2018 to July 2023) of political contributions through a scheme that has proved destructive to democracy. While the court has tried its best to remedy the effects of the delay through several directives to the State Bank of India (SBI) and the ECI, it’s clear that some damages are now irreparable.

Nuts and Bolts of EBS

Promulgated under Section 31 (3) of the Reserve Bank of India Act 1934, the Electoral Bonds Scheme upended the legal framework of electoral funding by providing complete anonymity to political donors. Briefly, the scheme allowed persons (individuals, companies, partnerships etc) to purchase electoral bonds that would not carry the name of the payee. The bonds could be encashed by the political parties that received them within their validity period (15 days). At the core of the scheme was rule 7.4, which stipulated that information about the purchaser of electoral bonds would be kept confidential by the SBI, which was designated as the sole scheduled bank for transactions involving electoral bonds.

In addition to the above, the following set of interconnected amendments in various legislations were incorporated through the Finance Act 2017 to implement EBS.

Proviso to Section 29C (1) of the Representation of People Act

Originally, Section 29C provided that political parties had to maintain records of any person or company (other than a government company) from whom they have received a contribution of more than Rs 20,000 in a financial year. This was amended to exclude contributions received through electoral bonds from this requirement.

Section 13A (b) of the Income Tax Act

The amended provision mandated that for contributions above Rs 20,000 made through electoral bonds, political parties did not have to maintain names, details and amount of contribution by donors.

Section 182 (3) of the Companies Act

Before 2017, companies were required to provide details of the political parties they contributed to along with the amounts of profit and loss in their statement. This provision was amended to the effect that companies had to only provide the overall amount that they contributed to political parties without specifying which political party/parties the contribution was made to.

Proviso to Section 182 of the Companies Act

Earlier, the amount a company could donate as a political contribution in a given financial year could not exceed 7.5 per cent of its average net profits during the three immediately preceding financial years. This proviso was deleted. Consequentially there was no upper limit on the funds that could be contributed by companies. Additionally, a company also became eligible to make political contributions even if it was not earning any profit.

Also read:

Scrapping the whole thing

The EBS has been declared unconstitutional in its entirety. Additionally, the above-mentioned amendments in the Representation of Peoples Act, Companies Act and Income Tax Act, which were specifically designed to facilitate the implementation of the scheme, have also been declared unconstitutional. The proviso to Section 182 of the Companies Act was struck down for being violative of Article 14, while all other provisions were found to be violative of Article 19 (1) (a).

As a consequence of all these provisions being declared unconstitutional, SBI has been directed to not issue fresh bonds with effect from 15 February 2024. In addition to the same, the ECI has been directed to publish on its website by 13 March 2024 information on all electoral bonds purchased along with donor details (name, date of purchase and amount) and also information on each electoral bond encashed by political parties between 12 April 2019 and 15 February 2024.

The ECI shall publish it after the SBI supplies this information to it by 6 March 2024. All electoral bonds that have already been purchased but have not yet been encashed are supposed to be returned to the banks by those in possession of the bond, i.e. the purchasers of the bonds or the political party.

Justice Khanna said that, considering 12 April 2019 was the date of the interim order of the court, contributors could have been under the assumption that their identities could be recorded and disclosed. However, the same principle does not apply to those who had contributed before the aforementioned date.

Also read:

Balancing of Rights

The core of the judgment lies in the finding that the EBS did not seek a harmonious balance between two constitutional rights – the right of informational privacy of political donors and the right of voters to be informed about political contributions. When the Constitution itself provides a hierarchy of rights, conflict resolution is simple as the superior right is enforced at the expense of the other right (the right to freedom of religion is subject to other fundamental rights and thus will cede ground when in conflict).

When the Constitution does not provide any such hierarchy, the judicial approach is to balance the rights. The court has found that the EBS scheme tilts decisively in favour of donor privacy at the complete expense of voter rights. The only time indentites were disclosed was when the court demanded details, or if a criminal case was registered by any enforcement agency. The court noted that these exceptions provide no avenue for information disclosure to the voters. While the main rule regarding confidentiality addressed the privacy rights of donors, the exceptions did not address the voter’s right to information.

The court also highlighted how the provisions in Section 13A of the Income Tax Act and Section 29C of the Representation of Peoples Act (before the 2017 amendments) provided a balanced solution wherein neither of the competing rights were excessively restricted. Under the earlier scheme, while donor privacy was enjoyed by those who contributed less than Rs 20,000 in a financial year, voters had the right to know about political contributions beyond Rs 20,000.

Such a solution ensured that bigger contributions, which had a higher likelihood of being made for political favours, were open to public scrutiny while smaller contributors enjoyed privacy. Complete blackout of information under the amended Section 182 (3) of the Companies Act was also found unacceptable wherein the companies did not have to disclose details of the political parties they had contributed to.

Also read: ‘Unlimited corporate contributions to parties contrary to free & fair elections,’ says SC

Overlooked nuances

For the most part, the reasoning of the court is robust and logically consistent. However, Justice Chandrachud’s acceptance of the informational privacy of political donors is not sufficiently founded. He very rightly points out that privacy regarding political affiliation is integral to a meaningful exercise of the freedom to vote and uses this as a founding stone for the proposition that political donors have a fundamental right to informational privacy. However, the primary purchasers of electoral bonds (in value) are believed to be companies. And companies do not vote.

There was a clear opportunity to distinguish between the privacy rights of individuals who vote and companies who don’t. It is interesting that Justice Chandrachud clearly states that in capping the limits of financial contributions, individuals and corporations cannot be equated, and must be treated separately. However, when it comes to political contributions, he equates the privacy rights of individuals and corporations. Justice Khanna does express scepticism in this regard and is convinced that corporations can have privacy rights only to a limited extent. However, he does not engage with this issue beyond expressing his reluctance to accept what was readily accepted by Justice Chandrachud.

Also read: 100% for BJD, 99% for DMK — electoral bonds a big chunk of ‘donations’ to regional parties in FY23

The cost of the delay

Throughout the judgment, the court has been categorical about the corrupting influence of money on the exercise of political power. It constantly emphasises how important it is for voters to make informed decisions and that details of political contributions are critical to the functioning of democracy.

However, what would have been a landmark decision in 2018 becomes a somewhat tainted decision in 2024, not because of its content, but because of its timing. In an ideal world, this decision should have been delivered before the 2019 Lok Sabha elections.

A very clear timeline set by the court suggests that it is conscious about making the information available to people before the 2024 Lok Sabha elections. However, one wonders if that leaves enough time for voters to untangle the web of quid pro quo, which may or may not exist but which the court constantly warns about.

Despite the lofty rhetoric in the judgment, the fact remains that history will record two general elections and many state election cycles under the cloud of a scheme that was inherently hostile to the idea of free and fair elections. One gets a sense that this judgment comes as a vaccine for the future and not as a medicine for the present.

Rangin Pallav Tripathy is Professor of Law and Director at the Centre for Public Policy, Law and Good Governance, National Law University Odisha. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)