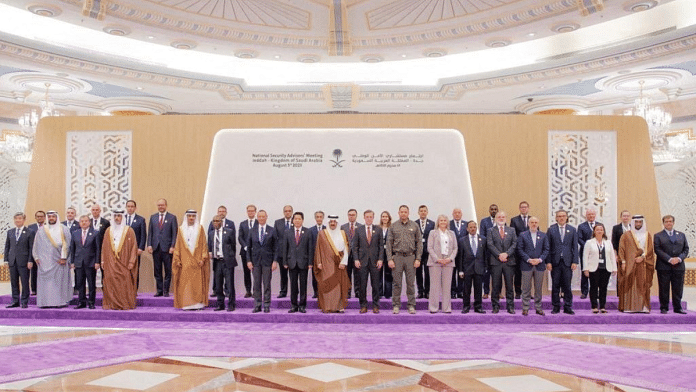

The most recent attempt at ending the war in Ukraine was made by Saudi Arabia last week. Representatives from 40 countries, including three BRICS members and other emerging economies, gathered in Jeddah on 5 August to discuss peace plans for Ukraine. India was represented by National Security Advisor Ajit Doval and Russia was not invited. It is intriguing why Saudi Arabia gave Ukraine an unprecedented platform a second time over to voice its opinions — with no Russian view to balance them.

The Jeddah summit came shortly after the Copenhagen talk where the G7, China (which skipped the event), India, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, and Brazil were invited to discuss Zelenskyy’s 10-point peace plan. Russia was kept out then as well.

While the Jeddah meeting became a winsome PR exercise for Zelenskyy in putting forth his peace plan, no concrete headway was made toward its actualisation. Almost all the important countries — China, India, and Brazil — emphasised that any meaningful peace plan must logically have Russia on board.

Nonetheless, the fact that they chose to attend the meeting knowing Russia was not invited provides a richer texture to their understanding of the direction of the war.

As it stretches on, the Ukraine war’s duration is turning inversely proportional to Russia’s superpower status. Regardless of the outcome of the war, Moscow will find itself pushed into Beijing’s lap, dependent on it for its strategic posturing and economy.

The Jeddah talk became a perfect platform for Kyiv to start a direct dialogue with countries with which it lacked diplomatic conversation or clout so far. The absence of any Russian contingent to object to the proceedings or to stage walkouts enabled the Ukrainian delegation to put forth its view. That itself seems to be the primary purpose of the talks. Moreover, it reflects a growing desire on the part of the hitherto neutral countries to posture themselves as mediators, despite official neutrality.

What’s significant here is not the obvious reiteration that common ground for compromise cannot be reached until Russia is brought on board. It is the repeated platforms provided to Ukraine by countries that are considered friendly to Russia.

And the list of mediators is only growing: Saudi Arabia has joined Israel, Turkey, China, India, and Brazil. None of the peace plans has worked and there has not been a single ceasefire yet, though. The reason is obvious — there is no common ground between Ukranian and Russian demands.

Also read: Delhi must push Russia to open Black Sea ports. Africa won’t get Indian rice…

Fundamental deadlock

In the Russia-Ukraine crisis, the most fundamental deadlock arises on the question of territorial integrity. Kyiv has made clear that its 1991 borders, which include Crimea, are sacrosanct; while Moscow has declared the eastern and southern Ukrainian regions it annexed in 2022 as Russian territory. And on this aspect, Moscow seems to be unflinchingly resolute.

Any efforts to bring about peace make little sense till Russia and Ukraine’s versions of territorial integrity remain incommensurate. With such a deadlock, parroting respect for international law, the United Nations Charter, sovereignty, and territorial integrity is bound to get reduced to rhetoric.

The second concern here is the ceasefire conundrum. Despite long-standing conflicts and wars, good mediators are known to work out a ceasefire and then push for negotiations and compromise.

It’s not surprising that this view is particularly popular in New Delhi. India has managed the Line of Control (LoC) crises with relatively stable ceasefire agreements over the years.

But Ukraine has rejected any agreement around a ceasefire and has demanded that Russian troops first withdraw from all Ukrainian territory and reinstate the status quo ante. From Kyiv’s perspective, any ceasefire with the Russian troops still on Ukrainian territory will only help Moscow freeze the conflict in its favour. This would be counterproductive to Ukrainian aspirations, which are already impeded by the slow pace of the counter-offensive.

While the geolocated footage published on 9 August shows that Ukrainian forces have continuously made advancements, taking back village after village over the months, but that alone doesn’t add up to great news The counter-offensive is still not able to achieve the breakthrough required in the first line of defence. Russian fortifications, with their trenches and landmines, are sturdy. With this pace, the probability of a painfully contracted conflict is getting higher by the day.

Also read: Germany can help EU de-risk from China. It will break Xi’s ‘bypass the collective’…

What is Ukraine’s calculus?

The counter-offensive seems to operate not only along several axes from north to northeast to south, but it is also focused on isolating Crimea. Then, there is a third aspect — to destabilise Russia internally and attack its logistics. The Ukrainian capacity to deep strike into Russia, admittedly, has improved considerably over the last year.

Long story short, the Ukrainian calculus in the counter-offensive is unfolding in parallel verticals. But, of course, there is a vector of time that wraps it all up. Kyiv realises that its window to ramp up pressure on Moscow remains effective only until the end of 2024. That is when the United States, the biggest military aid giver to Ukraine, will go into elections. Regardless of who comes to power, speculation is rife that US attention will be focused on the Indo-Pacific. Washington has made it clear to Brussels, Paris, and Berlin that Europe has to shoulder military responsibility for the war after 2024.

Therefore, any real persuasion to discuss a ceasefire will work when there is reduced support from the US, not before that. Likewise, chances are that war fatigue would affect all parties and the motivation to discuss ceasefires would be higher as 2024 ends. Regardless of what position Kyiv maintains under the overwhelming leadership of Zelenskyy and the stellar tenacity of its forces, with the American aid dwindling after 2024, it would have to recalibrate its conditions for a compromise.

The world is turning increasingly impatient with Russia’s war in Ukraine without a clearly defined objective. Whether Russia is able to retain the 18 per cent of Ukrainian land it has annexed till now is not a question that the world outside Europe is likely to engage with.

Russia’s grain gamble

Economic concerns around the globe are mounting, with compounding crises of food, fuel, and fertilisers. These anxieties deepened after Russia withdrew from the grain deal with Ukraine, perhaps in retaliation to Turkey’s sudden swing toward North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the US after Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s recent comeback. Russia, in the process, exacerbated the food crisis in the developing economies of North and Central Africa and the Middle East. Ukrainian grain exports have been critical in ensuring food security in these regions.

The impatience was palpable in the recently held Russia-Africa Summit where Moscow misread Africa’s apprehensions. To compensate for pulling out of the grain deal and to replace Ukrainian grains, President Vladimir Putin had promised ‘free on board’ Russian grains to select countries in the region. However, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa stated that what the Africans want is the grain deal back, not donations. Despite the ramp-up of Russian diplomatic flurry in Africa, the unease about Moscow’s actions is growing as only 17 countries attended the summit this time, compared to 43 when it was held for the first time in 2019.

How does that fit into Russia building diplomatic heft amid the emerging economies? The answer is that there is a misfit indeed. Europe, for its part, will have to find a way of dealing with Russia, but Moscow will also have to find a way to deal with the world and especially in the region that is increasingly becoming crucial for its influence. Russian hold in its traditional spheres of influence — in Eastern Europe, Caucasus, and Central Asia — has been declining since the war began.

How to meaningfully mediate

First, the mediators need to time their efforts more intelligently. Any call for either total mediation, i.e., bringing the war to an end or a ceasefire, will remain rhetorical at least until the 2024 US elections. As fears grow about the conflict turning into a war of ‘grinding attrition’, President Joe Biden is being pressurised by Ukraine and its own lawmakers to now send weapons such as the ATACAMS with a 190 miles range, the promised F-16s, and expedite the deliveries of M1 Abraham Tanks to speed up Ukrainian counter-offensive.

Ukraine’s nod to a ceasefire remains the most counter-intuitive argument amid current developments.

Second, the international community should take on a more ingenuous perspective and push for ‘limited/tactical mediation’ around specific issues. The grain deal was a brilliant example of successful limited mediation that stayed the course for a year. It is likely to get revived because of pressure from Africa as well as from China, another country that depends on Ukrainian grain for its food security. It is a less-known fact that China remains the largest recipient of the grain deal, snapping at least 25 per cent of the total grains exported from Ukraine.

What the world needs today is brainstorming over tactical mediation strategies — the return of prisoners of war and children and steps to outlaw chemical and biological weapons — that will bring a net reduction in the global suffering index as the war rages on.

Let us not forget that net global suffering will worsen with inflationary pressures bound to hit the global economy soon. Due to the high interest rates of almost all central banks, the pressure on sovereign debt shall be high and a ripple effect will follow.

Therefore, among the multitude of mediation efforts, toning down the shriller rhetoric embedded in the Ukraine war remains a long-drawn process. The focus should be on reducing the net global suffering by tactical strategies to ease the dreaded inflationary tsunami and on reinforcing ‘just war’ practices.

The writer is an Associate Fellow, Europe and Eurasia Center, at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. She tweets @swasrao. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)