It was the middle of the first century of the common era, and in the prosperous city of Rome, the capital of the great Roman Empire, a brilliant intellectual was writing a book called Natural History. His name was Pliny, best known as Pliny the Elder. He comments on Rome’s booming trade with India, deploring two of its adverse effects of globalisation. Indians loved Mediterranean red coral so much, Pliny complains, that coral had become scarce in the land of its origin. And Roman ladies loved Indian pearls and fine textiles so much that, to pay for them, much of Rome’s gold found its way to India. “So dearly do we pay for our women and our luxuries,” Pliny exclaims.

Recent historical and archeological studies have revealed the enormous volume and value of ancient Indo-Roman maritime trade via the Red Sea. Summarising some of the conclusions of these studies, the writer and historian William Dalrymple notes: “…custom taxes raised on the trade coming through the Red Sea would have covered around one third of the funds that the Roman Empire required to administer its global conquests and maintain its vast legions.”

It is clear that Roman trade with India far surpassed the much-heralded trade via the Silk Route. Dalrymple further observes: “Contrary to popular ideas about the overland ‘Silk Roads,’ it is now clear that historians have been looking at entirely the wrong place when they thought about ancient trade routes. It was India, not China, that was the greatest trading partner of the Roman Empire.”

Also Read: Silk Route talk irritates Dalrymple. His new book says India, not China, ruled trade, ideas

Insights from the Arthashatra

Globalisation is not a uniquely modern phenomenon. Variants of it can be found in every period of history. Indian and Arab traders became skilled at using the monsoon winds to navigate the Indian ocean and to bring large ships laden with goods into Indian and West Asian ports. Trade with the Roman Empire began around the second century BCE and reached its peak in the first century CE.

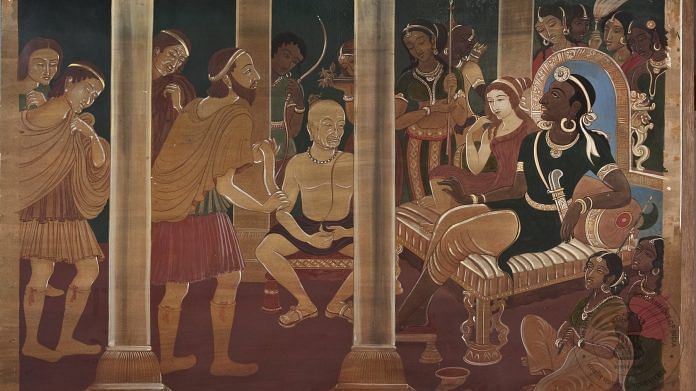

At about the same time as Pliny was writing in Rome, another brilliant intellectual called Kautilya was composing his magnum opus, the Arthashastra in northern India. It has been called the most precious work in the whole range of Sanskrit literature and provides a glimpse into international trade from the Indian side.

Kautilya gives a bureaucratic description of international trade and its legal underpinnings. While outlining the duties of the superintendent of the treasury (koshadhyaksha), he lists nine categories of precious commodities deposited in the treasury. They are pearls, gems, diamonds, coral, sandalwood, aloe, incense, skins and furs, and cloth. Names of different varieties of these commodities are toponyms derived from their places of origin, much like today’s Bordeaux wine or Ceylon tea. These places were far from the Kauṭilyan home territory and often located overseas.

Although it is often difficult to identify place names of pearls, they were located mostly in the southern regions of the subcontinent, as well as in overseas locations such as Sri Lanka.

Diamonds & wine to military animals

Kauṭilya documents two major trade routes, the northern and the southern. The northern route is said to have included merchandise such as elephants, horses, perfumes, ivory, antelope skins, silver, and gold, while the southern had an abundance of conch-shells, diamonds, gems, pearls, and gold (Arthashastra 7.12.22–24).

Red ornamental coral was another precious commodity that, as Pliny noted, came from the Mediterranean region. Two kinds are noted: Alakanda, which is associated with Alexandria in Egypt, the transportation hub for Mediterranean trade, and Vivarṇa identified by commentators with the Greeks, possibly originating from the Persian Gulf or the Mediterranean. Precious woods, such as sandalwood, aloeswood, and incense were brought from south India and Sri Lanka, as well as the northeastern regions of the subcontinent, including present-day Assam and Myanmar.

The provenance of clothes, blankets, and furs extended even farther afield. Kauṭilya writes of blankets from Nepal, furs from northwestern regions, including today’s Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, and cloth from Bengal and China, especially silk called chinapatta. Liquor and salt were lucrative state monopolies, but some varieties were imported. A liquor called kapishayana, for example, likely originated from the Kabul region of Afghanistan. Grape wine, likewise, was imported. Some probably came from the northwestern Asia, where grape vines grow, while Roman wine containers, called amphorae, have been excavated in south Indian ports such as Arikamedu.

A major area of international trade in antiquity was military equipment. The ancient equivalents of today’s tanks and armored personnel carriers were the war elephant and the war horse. In fact, one key article in the peace treaty between Chandragupta Maurya and Seleucus Nicator around 303 BCE was the transfer of 500 war elephants to the latter. Several regions of India produced the best fighting elephants, sought after for import by the armies of western empires. However, India did not breed good horses. The best horses had to be imported from the what are today’s Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Think of the colourful Pashtun horse trader in Rudyard Kipling’s Kim.

As Professor Thomas Trautmann has admirably demonstrated in his superb book Elephants and Kings: An Environment History (Chicago, 2015), there was an interesting bilateral trade arrangement, with horses going from west to east, and elephants going from east to west. This was one of the most fascinating and longest lasting examples of ancient Indian international trade. Controlling this trade was lucrative to a king both economically and militarily as it crisscrossed northern India.

Also Read: Kautilya was no Machiavelli, he’s the most pre-eminent economist in history

Ancient trade infrastructure

International trade does not happen on its own. It requires infrastructure: secure maritime and overland routes, security for traders within host countries, and a fair legal system so that traders are not subjected to unjust prosecution.

We see all these requirements addressed by Kautilya. Caravans entering a kingdom stopped at frontier posts and had their contents examined and catalogued. Then, the packages were sealed with the king’s stamp. Within the kingdom, the caravans were given a military escort for the payment of a levy. They were expected to go directly to the customs house located outside the main gate of the king’s capital city or fort. Smuggling and attempts to avoid duties were as prevalent then as they are now, and Kauṭilya instructs the Superintendent of Customs to be alert to all the stunts foreign traders may try to pull off.

Kautilya has detailed rules about customs duty, but the general standard was that imports were taxed at 20 per cent, similar to the 25 per cent levied by Rome according to the Muziris Papyrus. Foreign importers were not permitted to enter the local retail trade. At the customs house, their goods were sold or auctioned to local retail traders.

The Arthashastra (3.11.1–10) also provides valuable insights into financing, without which long-distance trade would have been impossible. Interest rates varied depending on the risk borne by the lender: 5 per cent for commercial loans, 10 per cent for traders travelling through wild tracts, and 20 per cent for maritime trade.

Kauṭilya’s world—at least when it came to overseas trade—extended from Nepal and China in the north, to Assam, Bengal, Orissa, and Myanmar in the east, to Sri Lanka, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala in the south, and to Afghanistan, Persia, and the Mediterranean region in the west. Together, these regions constituted much of the then-known world.

Further Reading:

Matthew Adam Cobb. The Indian Ocean Trade in Antiquity. London: Routledge, 2018.

Patrick Olivelle. “Long-distance trade in ancient India: Evidence from Kauṭilya’s Arthaśāstra.” In The Indian Economic and Social History Review, 2019: 1–17.

Patrick Olivelle is Professor Emeritus of Asian Studies, The University of Texas at Austin. He is known for his work on early Indian religions, law, and statecraft. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)