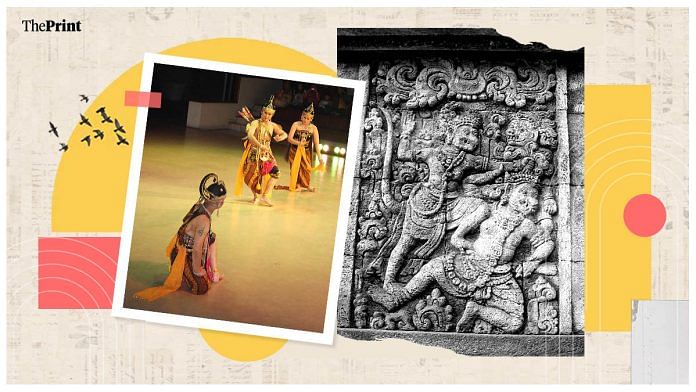

The story of Rama stands out as one of medieval Asia’s best-known, adapted and spun by rulers and poets from Central Asia, throughout the Indian subcontinent, and into the endless archipelago of Southeast Asia. Wherever it went, it was enriched by new cultures, new languages. In the islands of present-day Indonesia, the Rama legend evolved into its most creative and striking versions, developed by Sufi preachers and devout Muslims, both at royal courts and in lively popular theatre.

Also Read: Rama and the King: How an ancient hero was used by Pala poets, Chola emperors

The Ramayana in the vernacular

On the island of Java in the 9th or 10th century, an unknown poet completed his masterpiece: the Ramayana Kakawin. He lived in a world that had been ‘globalised’ for many centuries. The courts of Java were intimately connected to those of Bengal, and merchants and monks from as far as present-day Gujarat and Sri Lanka lived on the island. This poet was well aware of Sanskrit texts circulating in the Indian Ocean world, including the Bhattikavya, a retelling of the Ramayana in polished contemporary Sanskrit, making full use of the language’s grammatical features.

As his medieval Indian contemporaries did, this poet used the Ramayana for his own political and cultural purposes. Rather than Sanskrit, he wrote in Old Javanese, a significant departure from the intellectual culture of his time.

As historian Malini Saran and diplomat Vinod Khanna write in The Ramayana in Indonesia, the poet followed the Bhattikavya for the first portion of his narrative but made significant developments in characterisation, emotional depth, and dialogue. He also grounded it securely in Javanese cultural ideas, summarised by Saran in her paper ‘The Ramayana in Indonesia: alternate tellings’. In the 9th century, the placenta was believed to have magical powers; as such, the bow won at Sita’s wedding is a magical reincarnation of her birth placenta. Trijata, the daughter of Vibhishana, is a major character in the Kakawin. She serves as Sita’s loyal companion—so loyal that she does not hesitate to chastise Rama when he questions his wife’s loyalty.

In Valmiki’s Ramayana, Rama has little to say to Vibhishana when he grants him the throne of Lanka. The Kakawin, however, Rama delivers a powerful discourse on kingship, which would be quoted and repeated in Java for centuries after. The body of the king, declares Rama, contains eight deities, each representing a virtue which he must follow: generosity, like Indra’s rains; punishing the wicked, like Yama; delighting the good, like the glow of the moon. This was a powerful snapshot of how Javanese litterateurs imagined kingship in the 9th century. But it was only one among many circulating strands of the Rama legend, which wandering medieval bards and singers also took to with relish. Their embellishments have not survived from this early time. It would be a few more centuries before they were compiled, in a very different politico-religious culture.

Also Read: Buddha used to be Vishnu in India. In Sri Lanka, Vishnu is a future Buddha

Muslim Ramayanas

West Asian traders and sailors were active in Java even before the birth of Muhammad in the 7th century, but Islam only arrived there many centuries later, in the 13th century. The question of where Indonesian Islam was disseminated from, and how the archipelago converted largely without violent conflict, is a knotty one and deserves a separate column. In A History of Islam in Indonesia, historian Carool Kersten argues that though the islands had a rich Hindu-Buddhist history, membership within the wider Indian Ocean Muslim community may have offered protection against their most dangerous rivals—the mainland empires of Angkor and Siam. Arabic chronicles suggest that Sufi orders, established in the Hadhramut region of the Arabian peninsula, had some Javanese members at this time. The Hadhramut merchant diaspora may have helped in the conveying of teachers and texts between these regions, which had a flourishing relationship.

By the 16th century, rulers in Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula, and Java had converted to Islam. Islamicate legends and titles appeared alongside Hindu and Buddhist ones in state chronicles known as Hikayat and Sejarah. For example, in the Sejarah Malayu, commissioned by the court of Malacca, its ruling dynasty is said to be descended from Iskandar (Alexander the Great in his Islamicate form) and from Raja Chulan (Rajendra Chola). As Indologist S Singaravelu writes in ‘The Rāma story in the Malay Tradition’, Malacca Sultans also granted their admirals and generals the title of “Laksamana”, keeping with the old tradition that identified the king with Rama, and the legend that Rama appointed Lakshmana as commander-in-chief.

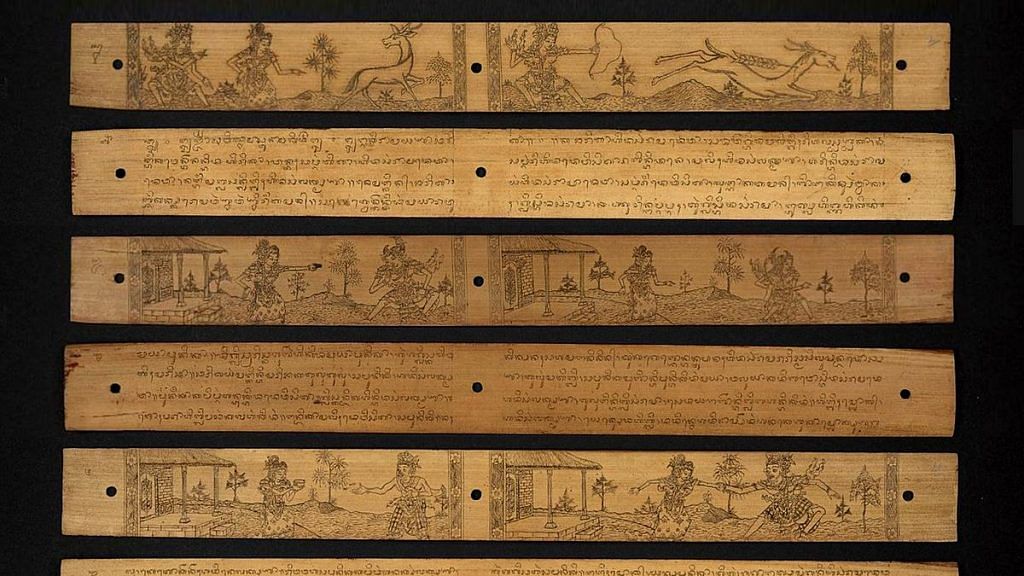

Saran and Khanna note in Ramayana in Indonesia that one tradition from Demak, northern Java, claims that its Sultan ordered the burning of older texts upon his conversion. However, they show that this rhetoric is disproven by the actual literary evidence from Javanese courts (and a plethora of other legends). Here’s a quote from an 18th-century Javanese ulema, recorded in the Serat Cabolek, a text documenting religious debates at the time: “the essence of kawi [medieval poetic] works is expressed in many metaphors from which the quintessence of mystical knowledge can be mastered… these, just as the books of Rama in kawi, are books on Sufism”. There was no contradiction, in the Javanese mind, between being a devout Muslim and revering Rama. Indeed, Rama’s discourse on kingship from the 9th-century Ramayana Kakawin continues to appear in texts from the early modern court of Mataram, such as the Serat Rama.

A particularly vibrant retelling of the Rama legend appears in an epic called the Hikayat Seri Rama, studied by Prof Singaravelu. It begins with the origin story of Ravana, banished to an island at the age of twelve for bullying his playmates. The Prophet Adam visits him and intercedes with Allah, who then grants Ravana dominion. In some versions, writes Singaravelu, Allah replaces Brahma, and Dasaratha is held to be Adam’s great-grandson, thus integrating Rama into Java’s Islamicate sense of history—no longer a god, but still a figure to be emulated.

By the 16th and 17th centuries, Indonesian oral traditions had developed every character in the Rama legend, giving them magical powers and intertwined backstories involving accidental seductions, gossip, and other shenanigans. These are still preserved in the Hikayat, and are so amusing that I recommend that readers look them up themselves. One of my favourite episodes: Hanuman sneaks into Ravana’s bedroom and ties the demon-king’s hair to his wife’s. He then leaves a note that the knot can be untied if Ravana’s wife beats him, which she does. This impish mischief, recorded in a Javanese Muslim chronicle, is a reminder that many weavers, great and small, have participated in the tapestry of Rama’s history.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)