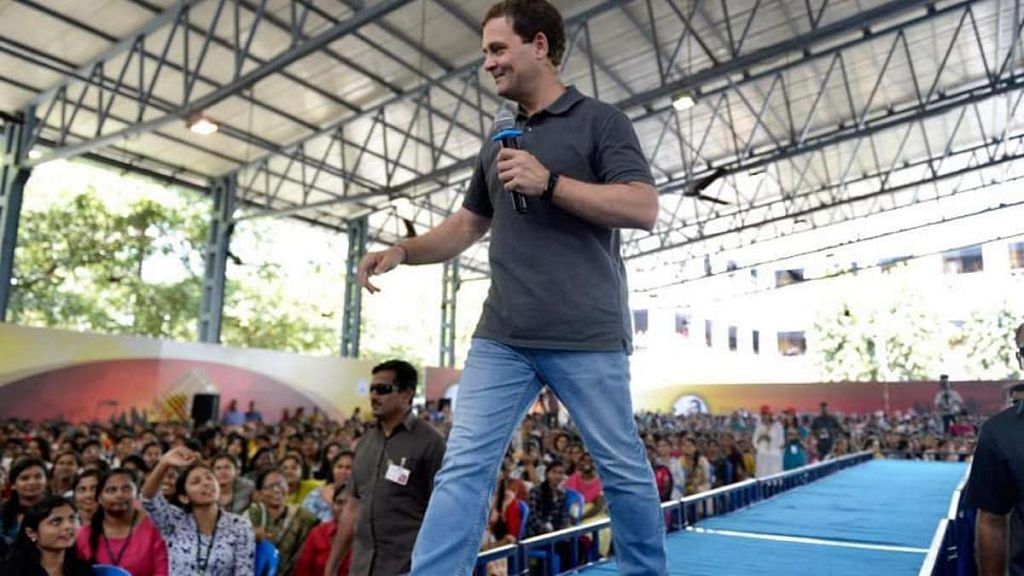

As 15 million young Indians in the age group of 18-19 get ready to cast vote for the first time in the coming weeks, the Congress has tried to catch their attention with one of its poll promises dedicated solely to them: no bank interest on educational loans during the moratorium period (course period plus one more year). In a Facebook post Sunday, Congress president Rahul Gandhi vowed to waive interests charged on educational loans until 31 March besides promising to create a one-window system for such loans. This comes after the Aam Aadmi Party’s 2015 promise on students higher education loans failed to take off.

Applying for a student loan in India is the classic case of low-paying, entry-level jobs requiring rich experience. As someone who has been through the ordeal, I can attest that the process is not only tedious but also dangerously discouraging for a student.

It should be a matter of concern for a country with more than half its population under the age of 25 (Census 2011), that conversations on or about students’ educational loans rarely make news. The focus, if and when, remain confined to skill development, vocational training etc. The ordeals of a student who wants to study but lacks the means remain ignored.

Also read: What Rahul Gandhi missed out when he promised higher GDP expenditure on education, NYAY

Can a student secure a loan?

India’s public sector banks (PSBs) are the largest lenders in the education sector, disbursing over 90 per cent of all loans. But what are the chances of a student securing a loan without much hassle? Take State Bank of India’s educational loan policy, for instance.

To begin with, regular student loans for education in India are capped at Rs 10 lakh and the bank’s policy mandates a parent or a guardian to register as a co-borrower. If a student’s parents work in the informal sector, have a bad credit rating, or are without jobs, then the chances of getting the educational loan are next to impossible.

Students getting into premier colleges have it relatively easy than their regular counterparts with the SBI’s scholar loan scheme relaxing the requirement while also keeping a bigger limit for the loan amount. However, the list of premier colleges is severely limiting and mostly covers engineering and management colleges. Banks flatly refusing loans for courses in humanities or anything that is not engineering or an MBA is fairly common. Bank officials say the loan applications are assessed based on the ‘employability’ factor associated with certain courses.

It was only in March 2018 that the Narendra Modi government notified the banks to increase the limit amount of loans that do not require a collateral or third-party guarantee as security — from Rs 4 lakh to Rs 7.5 lakh. Until then, the limit of Rs 4 lakh played like a cruel joke on students, considering how unlikely it is that a private university offers a course under that limit. This cap was increased from Rs 4 lakh only in March 2018 since the average loan size remained at Rs 4 lakh, possibly because a bulk of applicants did not have access to collateral or third party guarantee

But in case the institute revises the fee midway during the course, and the student has to move from the collateral fee category to another, then the ordeal in securing a guarantor while trying to finish the degree can be best left to imagination.

Also read: Indian nurses are not paying back their education loans

Interest waivers

Anyone who has successfully dealt with a public sector bank in their teenage years — possibly because their life depended on it — deserves a bravery award. Walk into the disbursement section during the admission season and you will see students in tears because the bank managers sometimes turn into career counsellors holding a cheque.

But only after completing the course does the real ordeal begin.

Banks charge interest during the entire period of study. And the interest rates for education loans remain one of the highest in the 10-11 per cent range. By the time the repayment begins, young graduates are drowned in debt. The Congress promises to do away with the interest if it comes to power. But election promises are great conversation starters; they should be followed up with policies once the party is elected.

The Congress-led UPA government did partially waive interest on education loans for economically weaker sections in 2014 but the plan announced in the interim budget. This partial waiver was only for households whose total income was less than Rs 4.5 lakh per annum.

One of the biggest problems with the educational loan structure is the notion that a student’s higher education must be funded only by the family. So, a family/household is identified for benefits like waivers and liability is shared by a parent as a co-borrower. While this is generally regressive, it leaves women the most affected in a patriarchal society like ours.

The scheme for interest waiver for Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and the Economically Backward Classes (EBCs) taking loans to study abroad, ostensibly in the name of Dr B.R. Ambedkar, is on a first-come-first-served basis till the banks fill up a mystery budget layout. Furthermore, the scheme doesn’t cover every applicant who meets the criteria.

Also read: The Modi govt’s education reforms that could have been

Rising NPAs?

Even though the number of people eligible for higher studies is increasing manifold, banks are dragging their feet in disbursing student loans. To defend themselves, they often cite the rising non-performing asset (NPA) problem. RBI data shows that NPA in education loans is indeed on the rise but a closer look at the numbers shows why this is not just a banking problem.

For example, the highest number of NPAs in educational loans, at 21.28 per cent, comes from students who took up nursing course. Fake degrees from unrecognised colleges are a widely acknowledged problem for courses in nursing, which perhaps explains the highest NPAs from this stream.

The remedy, therefore, lies at looking at these problems and finding innovative solutions rather than simply giving up on India’s future.

The author is a journalist based in New Delhi. She writes on law and the judiciary.