How do you build a museum with no objects? Imagine this—You have one bag, the clothes you are wearing, some food, and are walking across the high Himalayas in the dead of the night. You must not be seen by the Chinese patrolling guards, and it’s so cold that if you stop and rest, you will freeze to death. If you get caught in Tibet—‘prison and torture.’ Caught in Nepal—‘deported and handed over to Chinese authorities’. In these ruthless winter nights of escape, do you carry essentials or historical objects? This is why the Tibet Museum in Dharamshala’s McLeod Ganj is a ‘museum of absence.’

It’s built for and by Tibetans, and housed in the complex from where the ‘Tibetan government in exile’ works. The glass boxes in the museum haven’t all been filled, there are more photographs (30,000) and testimonials than objects. Emotions cover all works like dust.

Funded by the Central Tibetan Association, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the National Endowment of Democracy, the Tibet Museum is world-class unlike most museums in India. Tube lights and colonial-era placards don’t greet you. The display is modern, digital and direct. There’s the coveted museum merchandise—T-shirts, postcards, and bags. Most importantly, the museum has space for the future.

A future with climate change (you are told Tibet’s glaciers are melting at a faster rate than anywhere in the world), a future with more Tibetan objects (the ‘Free Tibet’ bags you buy in Dharamshala are part of the tour), and a future with an even more powerful China. Of course, it escapes no irony that the museum with the strongest emotions against China has been partly funded by the Americans.

Not on the Maggi-mountains-and-waterfall tourist path, it’s easy to miss the Tibet Museum. But take an hour out next time you are in the land of the Dalai Lama. As Nobel Prize-winner Orhan Pamuk says, “Real museums are places where Time is transformed into Space.”

Also read: 2020 was a do-over or die moment for museums. But there’s a new divide now

Pants, paintings, Partition

Witness paintings, patched clothes, political slogans, and sampa-grinders, the Tibet Museum inaugurated in February 2022 is the clearest example of ‘the personal is the political’. And why shouldn’t it be? Most museums I have visited in India tell the tales of royals, flaking oil paintings once commissioned by some white man, and gaudy ornaments that have no bearing on my life. They seem stuck in time—as do their placards with a date and a clinical description. They tell the story of some select people, most of whom aren’t underdogs.

Do museums have to be the personification of ‘Once upon a time, long, long ago’?

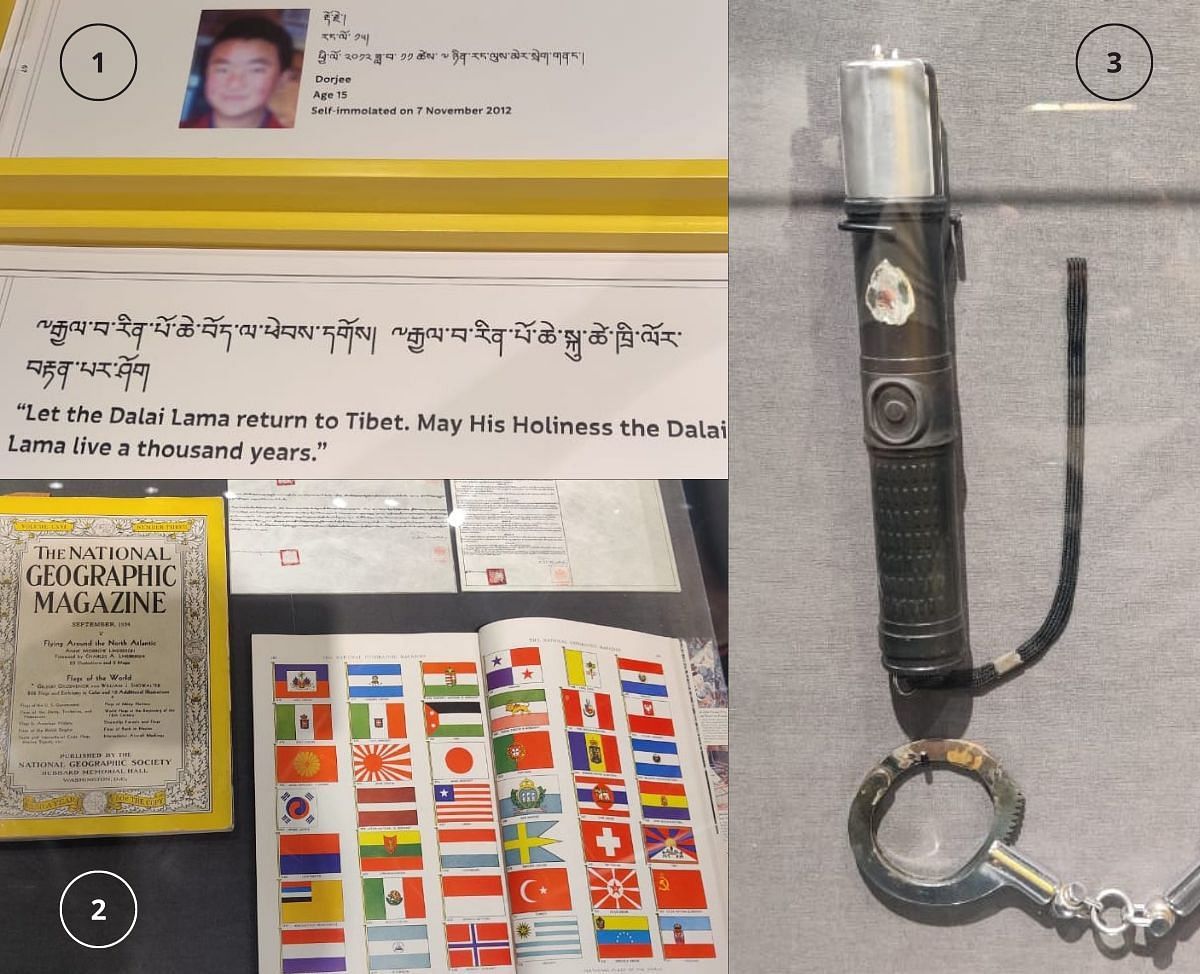

Here, in this one-floor Dharamshala museum, lies the last words and testimonials of monks who self-immolated to free Tibet. For instance, Dorjee who was just 15 when he burned himself in 2012 said, “Let the Dalai Lama return to Tibet.” There are knives, handcuffs and electric batons donated by the ‘Department of Security’ to show prison brutality against the Tibetans. A National Geographic magazine from 1934, that shows the Tibetan flag under ‘Flags of the World’, is displayed to prove the independence of the country before the Chinese marched in the 1950s. The magazine edition has no Indian flag because we were under British rule then. And there are the Dalai Lama’s answers to what I suppose are ‘FAQs’—’How do you relax’, ‘Can violence be used as the last resort’, and the like.

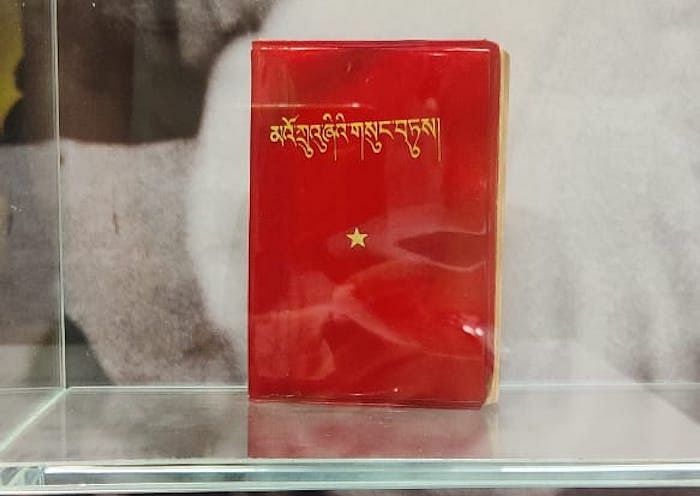

There’s also a copy of Mao Zedong’s Little Red Book that belonged to a political prisoner, Lobsang Yongden. Most Tibetans in Lhasa carried the book with them because they would be randomly stopped and asked to recite from it.

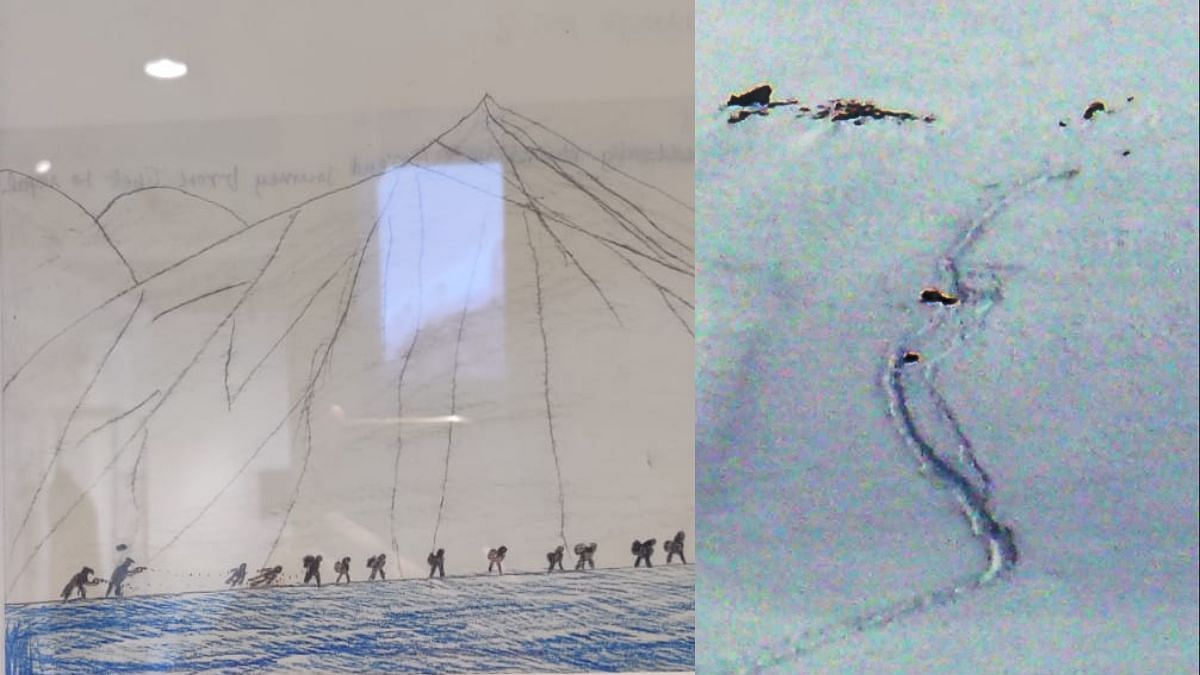

You may say this is heady stuff for a museum, too soaked in nostalgia and memories for any truth, but museums of refugees often only have oral histories to rely on. It’s the stories that become facts, and the memories that become hand-drawn paintings and proof. In the Tibet Museum, for instance, hangs a drawing by a 10-year-old boy who saw Chinese border guards open fire on his group from the back while they were escaping Tibet through the snowy Nangpa Pass as recently as 2006. One nun (Kelsang Namtso) was killed, while others sustained injuries. The boy was later part of a refugee art programme. You could dismiss the painting. But what the Chinese guards didn’t see was a group of mountaineers high up on the Cho Oyu mountain video recording the whole incident. They smuggled it out to show the world.

Most of the objects in this museum of absence, with empty glass boxes still, are things that would fit in your pocket, bag, trunk. Or they were worn, like the uniform of the Drapchi, the Tibetan army sworn to protect the Dalai Lama.

The building next to the Tibet Museum, which houses the archives, has some of the heavier objects of Tibetan life and culture: The browning pamphlets, the intricate Buddhas and tantric goddesses. All hidden and carried piece by piece to a new country, along with a government and a jigsaw puzzle of history.

It will remind you of the Partition Museum in Amritsar, in remembrance of the world’s largest forced migration. It depicts the experiences of people, through their stories and the sentimental items they carried. Words and works fill each other’s gaps in refugee museums. These museums stand on the stilts of donations, not aggressive acquisitions.

Also read: PMs’ Museum bedazzles and entertains. But it doesn’t tell us who we are

Bigg Boss, season Tibet

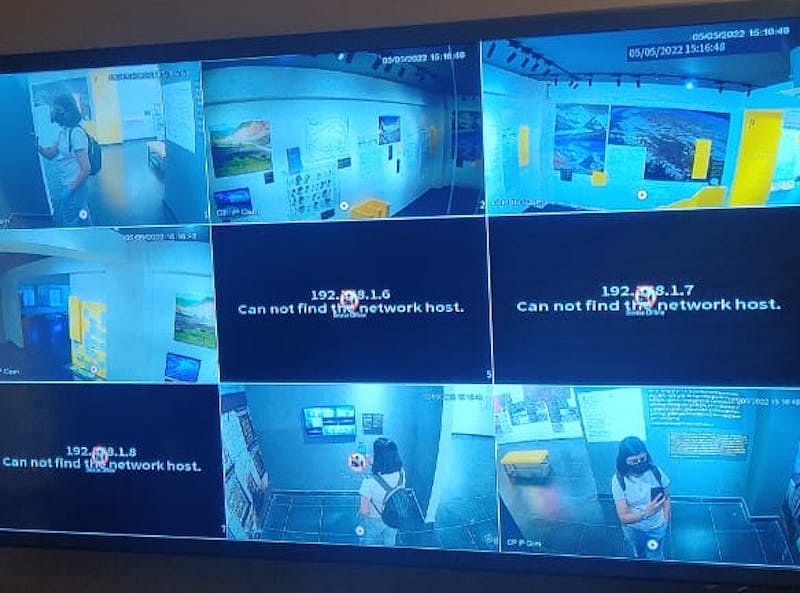

Right when you exit the Tibet Museum, comes an interactive shocker. You are projected across a row of nine security cameras.

‘Be careful…someone is watching you,’ the museum tells you. Then it asks if you would change your behaviour if you were being monitored 24×7. It claims that new prayer wheels in Lhasa come with in-built 24-hour cameras.

Outside the museum, back in 22°C of sweet sunshine and Himalayan peaks in the distance, a mother and daughter turn a row of Buddhist prayer wheels for luck. She holds her child up so her face can reach them.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)