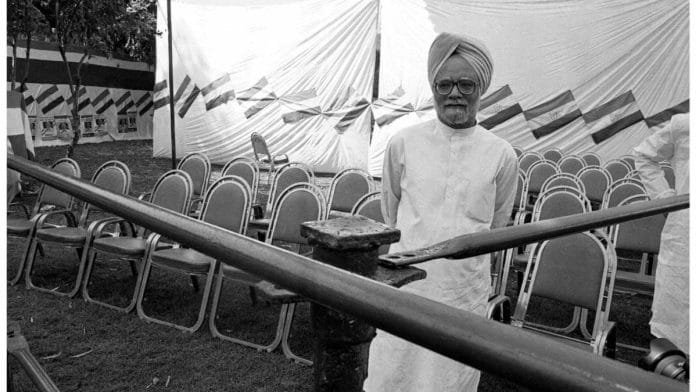

Only “Dr Sahib”, nobody else, knows the art of bathing in a bathroom with a raincoat on, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said about Dr. Manmohan Singh in February 2017. Modi said that his predecessor was associated with all financial decisions of the central government for 30-35 years when there were so many scams happening around him. “We politicians can learn a lot from Dr. Sahib. So much (scams) happened but it didn’t leave a single taint on him. Bathroom mein raincoat pahan kar nahaanaa, yeh kalaa toh Dr. Sahib hi jaante hain, aur koin nahin jaanta,” Modi said evoking peals of laughter from the treasury benches in the Rajya Sabha.

Many Congress leaders slammed Modi, saying that it was “unbecoming” of a PM to use such language about his predecessor. Singh refused to comment.

Modi had reasons to be upset with Singh who had severely criticised his demonetisation decision, calling it an “organised loot”. The Prime Minister’s sarcasm and insinuations aside, politicians do need to learn a lot from Manmohan Singh. Many of his Congress colleagues had also realised it soon enough.

Underestimated politician

In 2008, after the Left parties had withdrawn support from Singh’s government over the India-US civil nuclear deal, the Congress Working Committee (CWC) met to endorse the deal. A couple of days later, I was sitting with a powerful general secretary who never minced words while criticising the Singh-led government for “tom-tomming GDP growth” and his “obsession” with the nuclear deal. I asked how Singh could persuade Sonia Gandhi and the entire party to make a turnaround on the deal. He replied, “You don’t know him. Manmohan Singh is an over-estimated economist and an underestimated politician. If Narasimha Rao’s finance minister could become Sonia Gandhi’s Prime Minister, was it because of his economics?”

The senior Congress leader was never a fan of Singh’s liberalisation agenda, so his critique of Singh as an economist was understandable. But to call Manmohan Singh an underestimated politician! The former PM clearly got the better of his Congress colleagues on the nuclear deal and it hurt them.

At the core of his ‘politics’ was pragmatism, as explained through an anecdote by NK Singh, former chairman of the 15th Finance Commission, in The Indian Express on Friday. After the two of them failed to persuade then Petroleum Minister B Shankaranand (in PV Narasimha Rao’s government) to disinvest in government oil companies, Singh told NK Singh: “Don’t be so impatient. Please recognize that governments must survive to reform.”

Manmohan Singh was a patient man. Whether it was the India-US civil nuclear deal, foreign direct investment in multi-brand retail, or delinking dialogue with Pakistan from terror, he had to deal with party snipers every step of the way. His main task was to convince Sonia Gandhi. Once she agreed, others fell in line sooner than later.

Also read: Indian politics is going back to the pre-2014 era. What this means to Brand Modi and BJP

The hamstrung PM

In July 2013, the CWC endorsed the creation of Telangana by bifurcating Andhra Pradesh. As I reported for The Indian Express at the time, Singh and Gandhi had made the decision two months earlier, in May, but decided to go slow and convince other party leaders.

It was Sonia Gandhi who held the levers of power and Singh knew his limitations. He showed flexibility when Left-leaning activists and academics from the Gandhi-led national advisory council dictated policy decisions. He had to “survive to reform”. There was a permanent PM-in-waiting as his No.2 in the Cabinet—Pranab Mukherjee. So, Singh chose his battles carefully. Indo-US nuclear deal was one of them.

When the Left withdrew support and the Congress leadership scrambled to secure numbers for the trust vote in the Lok Sabha, Manmohan Singh was also quietly involved behind the scenes. The Samajwadi Party had already pledged its support, but smaller parties and their MPs needed convincing—they were extracting their pounds of flesh. Once these MPs made a ‘deal’ with the Congress interlocutors, they were taken to the PM’s residence to meet Singh, after which they would publicly declare their support for the UPA.

On one such occasion, a parliamentarian from a northeastern state was taken to the PM’s residence. As told by the Congress interlocutors, he put forth his demand for development projects in his constituency.

The PM told him that he would look into it. The MP, however, did not budge from his seat even after being prodded by the minister who had brought him to meet Singh. The PM looked puzzled. Finally, the minister had to ask the MP to leave. “But who will give THAT?” asked the MP. He was obviously expecting to finalise the deal then and there. The minister then hastily took him away. “You should have seen the PM’s face,” the minister told me a few weeks later, still laughing.

During Singh’s second term, then Environment and Forest Minister Jairam Ramesh, a Rahul Gandhi confidante, started stalling many infrastructure projects. Singh wavered for a while before promoting Ramesh as a Cabinet minister and shifted him to the Rural Development Ministry in 2011.

Two years later, as industrialists started complaining of arbitrary objections and rent-seeking in the Environment Ministry, Manmohan Singh again acted decisively. He got Ramesh’s successor Jayanthi Natarajan to resign.

That was in December 2013, with the Lok Sabha elections around the corner. A few days before that, Singh had conceded at the Congress Parliamentary Party (CPP) meeting that domestic problems were also responsible for the economic slowdown. He spoke about the clearances slowing down and affecting infrastructure projects. “We are trying to overcome these bottlenecks…. In retrospect, we should have done this one year earlier.”

Manmohan Singh could have done a lot of other things to course-correct long back. But he was hamstrung. He had to seek the approval of the Gandhis to even drop or shift a minister of state. Most of the Cabinet ministers owed their position to their loyalty to the Gandhis, not to him. And there was an heir apparent who could publicly call his government’s ordinance “utter nonsense”. History will be much kinder in judging Singh’s achievements. Given the constraints he faced, any other PM wouldn’t have achieved even half of what he did.

DK Singh is Political Editor at ThePrint. He tweets @dksingh73. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)