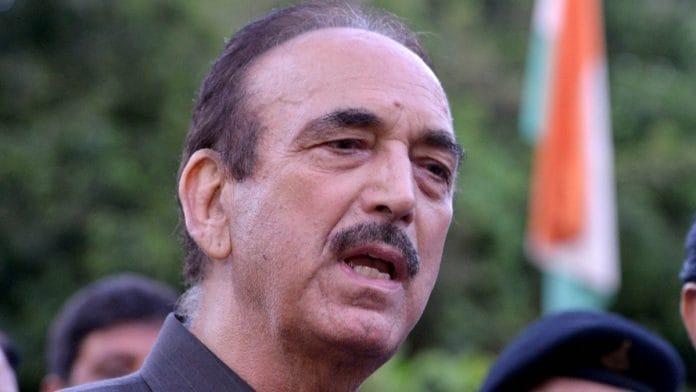

Ghulam Nabi Azad has got the political circles abuzz. At 72, he has fire in his belly. He can still draw crowds in Jammu and Kashmir. He addressed 10 public meetings from 16 November to 4 December, including two in the Valley.

It’s not the decent attendance in these meetings that has got Azad back into the headlines. Top politicians have started hitting the road for the first time since the abrogation of J&K special status in August 2019. And people are enthusiastic about it. Another former chief minister, Omar Abdullah, of the National Conference is drawing bigger crowds.

What’s creating the buzz is how Azad is no longer mincing words about Rahul Gandhi and Priyanka Vadra. “For saying no [to the Gandhis], you become nobody today,” he told the NDTV. He maintains he has been in the Congress for around five decades and will remain so. He says he has no intention to quit the Congress and float his own party, but also qualifies it: “No one can say what will happen next in politics.”

His reluctance to attack Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Union Home Minister Amit Shah during his public meetings has not gone unnoticed. Azad would rather question the development and employment claims of the Union Territory administration, headed by Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha. He would also not attack Sinha directly. While he told people how he had opposed the dilution of Article 370 in Parliament, he wouldn’t dwell on its reversal. He would rather leave it to the Supreme Court and fight for statehood. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) may not mind any of this.

So, what’s Azad up to? A quintessential Gandhi family loyalist, his decision to join 22 leaders to pen that controversial letter to Sonia Gandhi in August 2020 had surprised many. Probably, he had an inkling that Rahul Gandhi wanted to replace him as the Leader of Opposition in the Rajya Sabha with Mallikarjun Kharge. The Congress had nominated Kharge to the Upper House in June 2020. Azad’s apprehensions were proved right as the Congress high command chose to let his Rajya Sabha tenure lapse in February 2021.

If you ask Congress leaders about Azad in today’s context, they would take you back to Prime Minister Modi’s tearful farewell to Azad in the Rajya Sabha last February. “I will not let you retire… My doors are always open for you,” Modi told him in a choking voice then.

Azad also cried. It has been 10 months since then. But Modi’s words still echo in Congress corridors.

Also read: Goodbye Ghulam Nabi Azad — why Congress stayed silent when Modi cried, opponents praised him

Push factor for Ghulam Nabi Azad

Can Azad do an Amarinder to the Congress? Unlike the former Punjab CM who had left the Congress after Operation Blue Star in 1984 only to return after 14 years, Azad has been a Congress man all through his five decades in politics. The former Jammu and Kashmir CM has also arguably been the biggest beneficiary of the Gandhi family’s patronage. Look at his career. Two years after he won a Lok Sabha election from Maharashtra, Indira Gandhi inducted him as a deputy minister in 1982. He has been a minister in every Congress-led government since then. He was in Rajya Sabha from 1990 to 2021, except a gap of around three years — that too because he was made the J&K chief minister. Appointed All India Congress Committee (AICC) general secretary by Rajiv Gandhi in 1987, he went on to hold charge of almost every state and union territory in India. He has been a member of the Congress Working Committee (CWC) since 1987.

For someone who enjoyed fruits of power for so long with the Gandhis at the helm of the Congress, talks about the possibility of him abandoning the Congress is a mere surmise, for now. But many staunch Gandhi family loyalists have failed to cope with life without power. Azad knows better than anyone that you must have an exit plan when you attack the Gandhis. He has been doing it way too often, that too publicly.

One feels tempted to draw a parallel between Amarinder Singh and Azad. Both got clear signals from the Gandhis to hang up the boots. A month after G-23 wrote that letter to Sonia Gandhi, Azad was removed as AICC general secretary. Six months later, he was out of Rajya Sabha. Last month, he was out of the party’s disciplinary committee.

In Punjab, the Gandhis appointed Amarinder Singh-baiter Navjot Singh Sidhu the state Congress chief, which precipitated the CM’s fall. The Gandhis have been supporting the Jammu and Kashmir Congress chief, Ghulam Ahmed Mir, an Azad detractor. Twenty senior Congress leaders close to Azad, including four former ministers and three MLAs, resigned last month, demanding Mir’s removal. The Gandhis responded by dropping him from the disciplinary committee.

Also read: Why Congress & TMC’s alliances with Goa regional parties might not be enough to fight BJP

Can Azad go Captain’s way?

Azad has denied any intention of floating a new party. But he himself says no one knows what will happen next in politics. So, let’s look at his options. Unlike Amarinder Singh who never stayed away from state politics, Azad has essentially been a ‘Delhi man’, except for the three years (2005-2008) that he spent in Kashmir after becoming the CM. Since 2008, he has been promoting his loyalists based in the state but himself stayed put in Delhi. Singh had many things going for him — his support for agitating farmers all through, his soldierly stand on security-related issues concerning the border state, and Hindus’ lingering reservations against Arvind Kejriwal’s perceived dalliance with separatist Sikh elements, among others.

But for the need for resources and the challenges of rolling out a new political outfit, Singh could have gone alone without the BJP. Azad has no such advantage in Jammu and Kashmir. In fact, the Amarnath land controversy, which brought down his government, still lingers in public memory. He might have managed to mobilise decent crowds for his meetings, but that still doesn’t make him a mass leader who can swing elections.

Also read: Congress’ drive to fight & win missing — Meghalaya ex-CM Mukul Sangma after joining TMC

Azad has nothing to lose

The former J&K CM doesn’t have many options though. He can choose to remain in the Congress but he will then have to accept his virtual retirement. The second option is to wait for the Gandhis to see reason and stop treating the Congress as a proprietorship firm. But that won’t happen. The third one is to use the door the PM opened in his Rajya Sabha speech in February and float a new political outfit.

Unlike Amarinder Singh in Punjab, Azad can’t afford to have an open alliance with the BJP in Jammu and Kashmir but there can be a tacit understanding between the two. The BJP knows that, just like in Punjab, it can never form a government on its own in J&K either. It needs an ally. The Apni Party’s expansion so far hasn’t impressed the BJP leadership. Azad may not have a personality cult in J&K but he is an organisation man with a band of followers in the Congress.

Given the people’s disillusionment with mainstream regional parties in the Valley, Azad’s new party may have as good or bad a chance as others. With the BJP’s help in the Jammu region, he can hope to do better. That would open the BJP’s door to power in the union territory.

It’s a win-win situation for both the BJP and Azad because neither has anything to lose. Even if Azad’s new political venture fails to take off, he can always hope for a reward in some form or the other outside Jammu and Kashmir. For now, though, he may like to see how Amarinder Singh’s likely alliance with the BJP plays out in Punjab elections.

The author is Political Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @dksingh73. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)