The Nehru Memorial Museum and Library is now PMML — and the P, according to Congress leader Jairam Ramesh, stands for “pettiness and peeve”.

The Prime Minister’s Museum and Library, officially renamed on 14 August, follows an announcement by the NMML Society — headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi as president and Defence Minister Rajnath Singh as vice president, and comes over a year after the inauguration of the Pradhan Mantri Sangrahalaya in April 2022.

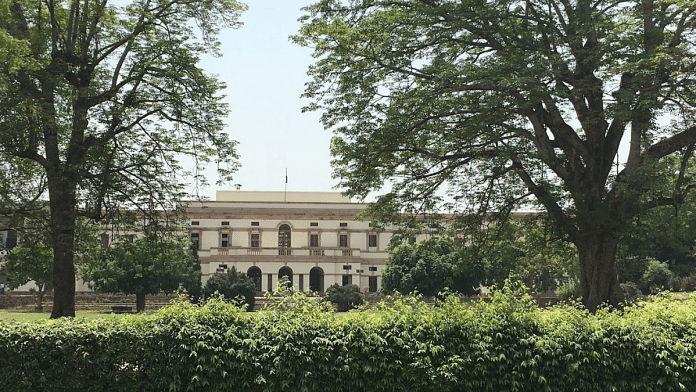

The NMML was situated within the Teen Murti Bhavan complex, which housed Jawaharlal Nehru for 16 years until his death in 1964. His residence was converted into a memorial museum, encompassing the NMML, Nehru Museum, and Nehru Planetarium. So, the BJP’s decision to expand the museum into the Pradhan Mantri Sangrahalaya to honour all prime ministers was viewed as a deliberate step to slowly erase Nehru’s influence on modern India.

A former Prime Minister himself led the opposition to this renaming. In 2018, Manmohan Singh strongly advised Modi not to “change the nature and character” of the NMML, pointing out that such attempts were never made during Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s six-year tenure.

Now, five years later, the NMML has officially been renamed, prompting opposition from various quarters. And that’s why it’s ThePrint’s Newsmaker of the Week.

Also read: PMs’ Museum bedazzles and entertains. But it doesn’t tell us who we are

What’s in a name?

The renaming of NMML is not unexpected. Scholars and library visitors have walked past the construction of the new Prime Minister’s museum over the past months.

The renovated Pradhan Mantri Sangrahalaya — or Prime Minister’s Museum — an upgraded version of the Nehru Museum within the Teen Murti complex, features state-of-the-art technology, expanding its scope to include all of India’s prime ministers. While the original Nehru Section remains, a new wing is dedicated to other prime ministers.

And judging by the footfall, the renamed and renovated museum is a big hit.

But the Teen Murti grounds have always housed a museum and a library. Initially conceived as a memorial to Nehru, the complex turned into a repository of his prolific writings, letters, speeches, and an incredible library collection, alongside mementos and souvenirs. The NMML Society, established in 1966, prioritised maintaining the museum, establishing a definitive library on modern India, and fostering research on modern Indian history with special emphasis on the Nehruvian era.

Over the years, the archive has embraced various collections, such as private papers, oral histories, microfilms, old editions of magazines and newspapers, and manuscripts of all kinds — including the “papers of the nationalist leaders of modem India and other Indians who have distinguished themselves in the domains of politics, administration, diplomacy, journalism, social reform, science and technology, industry, education and other developmental fields.”

The archive and library is a goldmine for scholars, journalists, researchers, bureaucrats, and diplomats. It’s a repository of papers written by individuals who shaped modern India, including Homi Bhabha, Bhagat Singh, MK Gandhi, Aurobindo Ghosh, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, PC Mahalanobis, and former PMs like Lal Bahadur Shastri, as well as bodies like All India Congress Committee, All India Hindu Mahasabha, and All India Muslim League.

Thus, the criticism that the PMML doesn’t adequately honour others’ legacies is unwarranted. It just so happens that Nehru’s former home and memorial evolved into a comprehensive record of modern India, reflecting the ideals he championed as the country’s first prime minister.

The true worth of the museum isn’t lost on anyone who has visited the library and utilised its services. Its essence lies not in its name, but in the knowledge it holds and scholarship it facilitates. This has made Teen Murti complex what it is today, with its reading room, the barebones chai-and-snack canteen, the well-utilised auditorium, the gardens inhabited by peacocks, and the numerous scholars who have toiled at the library carrels.

Also read:

Missing the point

The decision to rename the Nehru Museum has predictably led to a war of words between the Congress and the BJP.

Rahul Gandhi retorted that his great-grandfather was known for his work, not his name. Jairam Ramesh accused Modi of “distorting, defaming and destroying Nehru and the Nehruvian legacy” due to personal insecurities. Shiv Sena leader Sanjay Raut suggested that the BJP satisfies itself by “changing names” because it “can’t create a history”.

From today, an iconic institution gets a new name. The world renowned Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) becomes PMML—Prime Ministers’ Memorial Museum and Library.

Mr. Modi possesses a huge bundle of fears, complexes and insecurities, especially when it comes to our first…

— Jairam Ramesh (@Jairam_Ramesh) August 16, 2023

The BJP has held fast to its line that all prime ministers should be honoured, not just Nehru. BJP MP Ravi Shankar Prasad hit back at Ramesh, saying that while the Congress only cares about Nehru and his family, Modi has given a “respectful position to all the PMs of the country at the museum.”

The vice chairman of the PMML’s executive council, A Surya Prakash, defended the decision by citing the expansive 28–acre grounds of the Teen Murti estate as the ideal site for such a project.

But the thing is, it isn’t solely about one prime minister and a museum bearing his name. The institution was initially meant to honour Nehru’s vision and has since evolved into a scholarly hub that fulfils that purpose by chronicling India’s journey and growth.

As historian Narayani Basu points out, reducing the NMML to a reflection of prime ministers and their contributions diminishes its scope as a research institution. “If anything, by only focusing on the contributions of prime ministers, one risks reducing them to being the mascots of different eras, rather than remembering them as leaders, capable of great mistakes as well as great successes,” she writes.

Ultimately, the essence of history lies in understanding the past to shape a better future. As long as the collections remain untouched, one can hope that a change in name won’t detract from the institution’s value — that a rose by any other name will always smell as sweet.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)