China has emerged as a leading participant in multilateral development organizations. In many ways, this is a welcome development. Today’s global challenges, including Covid-19 and climate change, require an international response and have prompted renewed calls for increased multilateral engagement by the major economy countries. This, combined with the recognition of multilateral institutions’ high standards for transparency and environmental safeguards, have led the United States at times to encourage China to step up its multilateral contributions. At the same time, countervailing voices focused on strategic competition increasingly view China’s multilateral participation with scepticism.

When the People’s Republic of China joined the World Bank in 1980, it was allocated 12,000 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) shares, becoming the Bank’s sixth-largest shareholder with 3.47 per cent of the voting power. By 2013, decades of rapid economic growth had propelled China to its current position as the IBRD’s third-largest shareholder, eclipsing France, Germany, and the United Kingdom with 5.03 per cent of IBRD voting power.

In many ways, China’s rise in stature at the IBRD mirrors its growth in influence across the multilateral development system. This is certainly true of China’s increasing voting share in the World Bank, IMF, and UN system, all of which tie financial contributions to economic size (see Figure 1). But China’s growing importance in the multilateral system is also the product of distinct policy choices made by the Chinese government. These policy choices go beyond the wealth-based financial contributions that dictate IBRD shareholding to include voluntary financing, borrowing, and commercial contracting. In concert, they make China a unique player in the multilateral system by virtue of to its simultaneous roles as a multilateral organization donor, shareholder, aid recipient, and commercial partner.

Fundamentally, China’s evolving role in the multilateral space requires us to reexamine the metrics we use to evaluate the scale and scope of its participation. This analysis seeks to address that gap. By collecting and collating financial, procurement, voting, and other data provided by the major development-focused multilateral institutions and funds, we have sought to provide a clear, cross-institutional, comparative picture of China’s role in multilateral development organizations and the evolution of that role over the past decade.

We find that China’s large footprint in multilateral development organizations today is manifest in five key dimensions:

- China’s economy drives the country’s position in some respects, with multilateral rules that tie shareholding and “assessed” contributions primarily to economic size.

- China’s voluntary contributions to multilateral institutions have increased dramatically over the past decade, but this growth has favoured some institutions over others. Relative to other major donor countries, China’s overall voluntary contributions to multilateral institutions leave considerable room for growth.

- Alongside China’s growth as a donor and shareholder, the Chinese government has continued to rank among the largest clients of the multilateral institutions, and until recently consistently among the largest borrowers of the multilateral development banks (MDBs).

- China has benefited commercially from multilateral institutions, with Chinese firms (state-owned and private) ranking among the top recipients of MDB procurement each year.

- Consistent with the practices of other large countries, China has sought representation in key leadership positions across the multilateral system.

Also read: Biden charts path forward with Xi as both leaders stress for more talks amid tensions

International financial institutions and funds

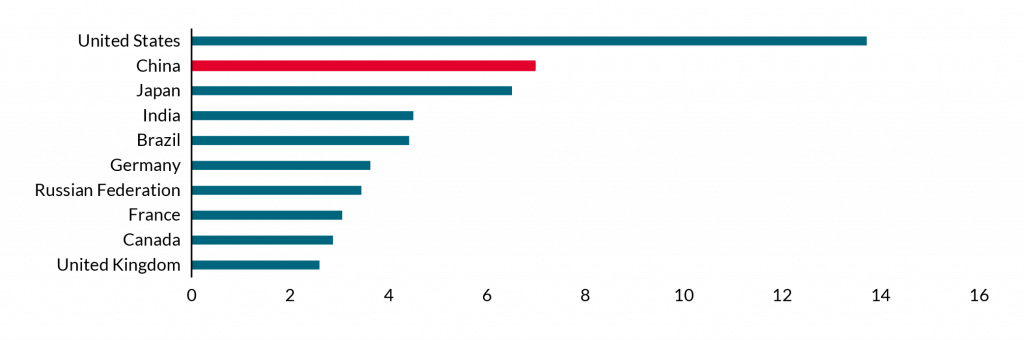

International financial institutions (IFIs) provide financial and technical assistance for development in low- and middle-income countries. China’s influence in the IFIs—primarily MDBs and regional development banks (RDBs) —has grown considerably over the past decade. China now has the second-highest aggregate voting power in the IFIs it supports, though it lags considerably behind the United States (see Figure 2). The biggest growth in China’s voting power over the last decade has been in the IBRD and the International Finance Corporation (IFC), both entities of the World Bank Group, as well as in regional development banks in Africa and Latin America. The launch of Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and New Development Bank (NDB) within the last five years—both with sizeable capital and in both of which China is the largest (or co-largest) shareholder—also contributes to China’s growing influence in the broader multilateral system.

Some of China’s increased voting power in the IFI system reflects China’s economic growth; shareholding in the IBRD and IFC are directly linked to economic size. However, China’s gains in voting share in some of the RDBs are the result of active efforts and discretionary share purchases on the part of the Chinese government. Large shareholders in IFIs generally possess influence in moulding institutional agendas and have vested interests in ensuring activities are well managed and well resourced.

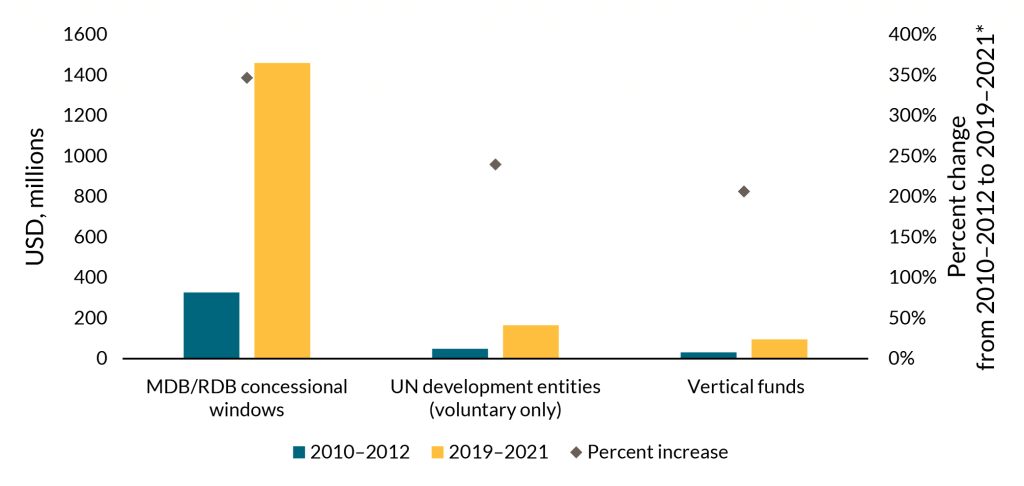

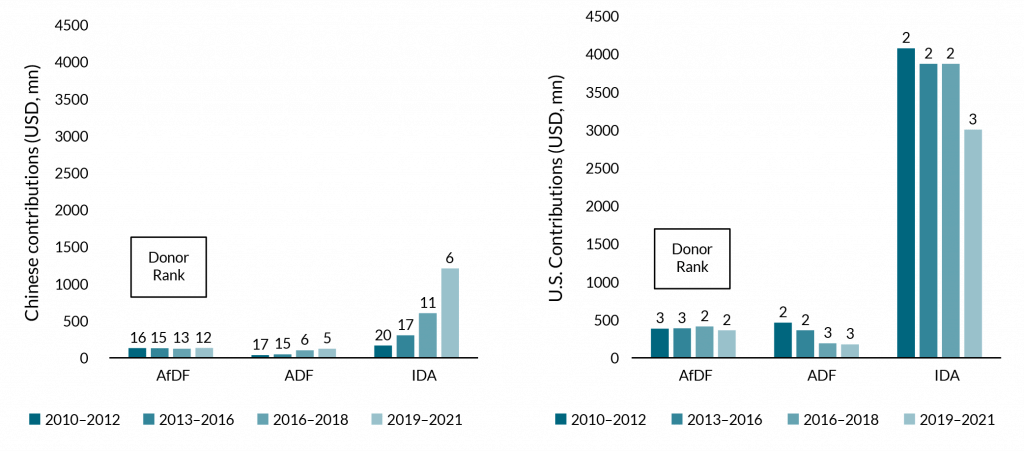

Unlike shareholding, contributions to development bank concessional financing windows (resources set aside to allocate to countries at more favourable interest rates and repayment schedules) are entirely discretionary. China has increased its support of these windows over the last decade, particularly for the World Bank’s IDA (Figures 3 and 4). Voting power within these entities is more limited than it is for MDB shareholding, but IDA contributions do factor into the formula for IBRD voting power.

In addition to institution-wide fundraising exercises through capital subscriptions (for the MDBs) and periodic replenishments (for concessional financing windows), China also contributes to a number of special-purpose funds associated with the banks that complement the institutions’ core funding. Worth particular mention are two $2 billion China-led funds associated with the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and African Development Bank (AfDB). These large funds can help increase China’s financing and influence where shareholding and voting power is limited by a region-based formula. For example, China contributes just $50 million (one per cent) of the AfDB’s $5 billion in paid-in capital.

Procurement

Chinese firms outperform firms from other countries in securing MDB contracts for goods, works, and services. In 2019 alone, Chinese firms won contracts from the IBRD, IDA, AfDB, IDB, ADB, and EBRD worth $ 7.4 billion (14 per cent of total contracts by value). This reflects institutional rules that favour the lowest bids for procurement contracts. It also reflects the heavy presence of Chinese firms in infrastructure sectors, which account for the largest value contracts at the MDBs. Though findings of corrupt practices arise in a very small share of MDB contracts, resulting in the debarment of implicated firms, Chinese firms account for a significant share of such debarments. Still, our analysis also suggests that through participation in MDB contracts, China’s firms operate under a highly transparent, rules-based system.

Also read: Biden, Xi seek to stabilise US-China ties in longer-than-expected summit

UN System

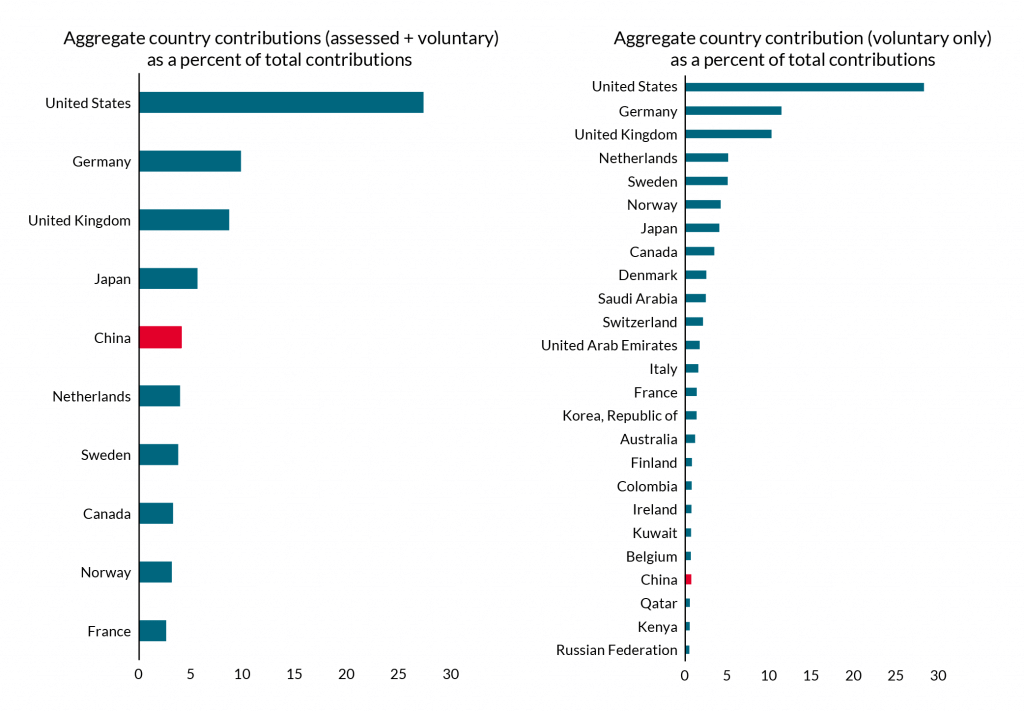

China is a top contributor to the UN’s development-focused entities, but this largely reflects its level of assessed contributions, which are based on economic size (Figure 5). For voluntary contributions, China ranks 22nd.

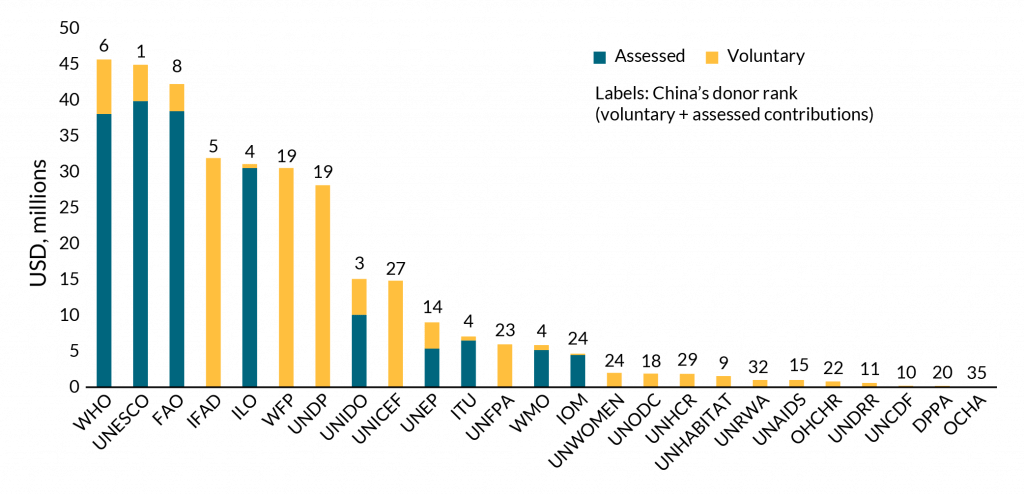

China’s largest contributions to the UN system (excluding its contributions to the regular budget and peacekeeping) go to the World Health Organization (WHO), UN Economic, Social and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). However, these are largely assessed contributions (Figure 6). China’s largest voluntary contributions, which are more indicative of China’s policy preferences, were made to the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the World Food Programme (WFP), and the UN Development Programme (UNDP).

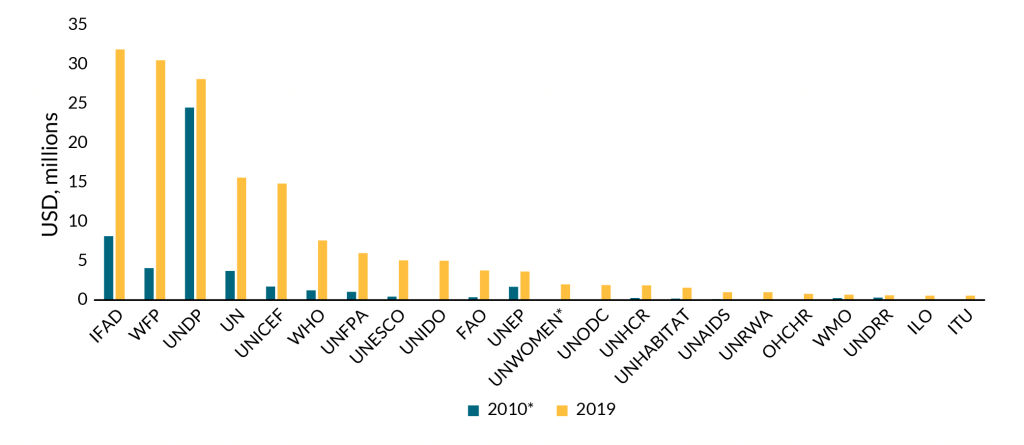

China’s voluntary funding of UN development-focused entities increased by 250% between 2010 and 2019. Particularly notable are the increases in China’s contributions to IFAD and WFP (Figure 7). This reflects Chinese policymakers’ recent focus on food and agriculture sectors’ role in development.

In addition to contributing to established UN entities, China also established, in 2016, the UN Peace and Development Trust Fund (UNPDF) with a commitment of $200 million over 10 years to advance peace and development objectives. As of 2020, China has put $100 million toward the fund.

Also read: IMF says US, China remain vital engines of growth in global economy despite slowing momentum

Vertical Funds

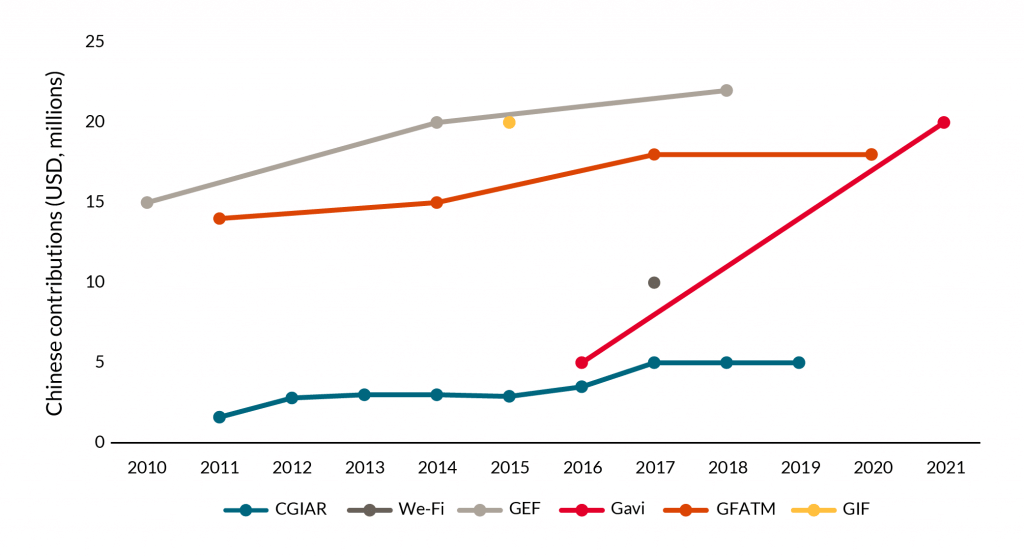

China is not a major contributor to vertical funds, single-sector development funds to which government and private donors voluntarily contribute. Across 18 large vertical funds, China ranked 22nd among government contributors for the 2010-2020 period (the United States ranked first).

That said, China’s contributions to vertical funds have doubled over the past decade, with the biggest increase going to Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (see Figure 8).

Conclusion

When it comes to global development efforts, the strategic competition now defines the stance between China and the United States, and to a lesser degree between China and the G7 countries. This poses a dilemma when it comes to China’s role in multilateral development institutions. Western countries have long encouraged China to step up its role as a donor to multilateral institutions, premised on the belief that multilateral aid will be better spent in developing countries than bilateral assistance, particularly in China’s case. This rationale remains strong.

At the same time, there are growing fears that China’s large footprint in multilateral institutions gives it undue influence and advantage, given its singular position as a large shareholder, donor, client, and commercial partner. But acknowledging the reality of the unique position that China holds in the multilateral system doesn’t undermine the call for China to do more as a multilateral donor.

It may, however, point to the need for further scrutiny in some areas, particularly where China may obtain advantages over other countries and actors in ways that undermine development goals and multilateralism.

For example, although MDB procurement rules aim to promote transparent and open bidding, Chinese firms have come to dominate MDB commercial contracts to a degree that undercuts political support for these institutions in other countries. Of course, any procurement reform efforts should avoid becoming a discriminatory spoils system for the largest MDB donors. But reasonable efforts to temper China’s dominant position could include broadening the measures of bid quality beyond price has been a recent innovation that deserves more consideration, as well as greater efforts to promote procurement opportunities, particularly in developing countries themselves.

Another area of scrutiny pertains to the rules and norms of multilateral development institutions as they apply to China’s bilateral behaviour. For example, the IMF, World Bank, and UNDP together play a leading role in working with developing countries to ensure access to finance that is sustainable, transparent, and offered on terms that are appropriate to each country’s circumstances. In cases of debt distress, these multilateral actors seek to guide commercial and bilateral creditors toward cooperative approaches to timely resolution. Today, the Chinese government factors prominently as a leading bilateral and quasi-commercial creditor in many cases of debt distress. Yet, China’s record when it comes to cooperation with multilateral resolution efforts is mixed. The multilateral institutions themselves have been measured in criticizing any of their member governments when it comes to their roles as bilateral creditors.

In general, the United States and other allied governments shouldn’t be alarmed by China’s position in multilateral development institutions today, and they should continue to promote China’s role as a donor to these institutions. That said, they need not be indifferent to areas where China’s multilateral relationships are at odds with their interests. Procurement and debt sustainability are two examples that merit greater attention. In the spirit of multilateralism, these agendas should be addressed cooperatively, with reform targets that are non-discriminatory even as they seek to address concerns about China.

Governments should seek to promote China’s participation in multilateral institutions for the same reasons they themselves participate: the leading challenges facing the world today require cooperation more than the competition. Whether the threat is climate change or a global pandemic, an effective response demands cooperation between China and other governments within multilateral institutions.

Scott Morris is Director of the US Development Policy Initiative, Co-Director of Sustainable Development Finance, and Senior Fellow. Rowan Rockafellow is Research Assistant at the Centre for Global Development. Sarah Rose is Policy Fellow at the Centre for Global Development. Views are personal.

This article was published on the Centre for Global Development.