A farmer spends anywhere between Rs 4 to Rs 8 to produce a kilogram of onion. If one included the cost of his own labour, capital, and land, this cost could rise to Rs 15 per kg in some states, as per the inflation-adjusted data from the Directorate of Economics and Statistics for 2019-20.

In February this year, the wholesale price of onions crashed to about Rs 6 per kg in Maharashtra’s Lasalgaon mandi, which is Asia’s largest onion mandi. There were reports about onion prices crashing to even Rs 2 per kg in some areas. This triggered the government into action as it directed the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (NAFED) to undertake procurement of onions from the mandi. As a result, the onion prices, which were nosediving, started to stabilise and recover to levels of about Rs 7.3 per kg by 7 March. Though it offered some respite to the farmers, it is only a bandage or a temporary solution at best to a structural problem that inflicts farmers of crops like onions and potatoes.

There is a need for state and central governments to undertake medium and long-term measures to provide stability to these markets.

Indian Onions—Rabi, Kharif, late Kharif

Onion in India is about a 3.5-month crop, which is sown and harvested three times a year. The three cropping seasons are Kharif, late Kharif and Rabi.

Rabi is the most important season producing about 75 per cent of India’s onions in a year. This crop is sown between December and January and harvested from end of March to May months. Kharif onion crop, the second most important, gets sown around the July-August monsoon months and is harvested towards the end of the same year. This season provides for about 15 per cent of the annual onion supplies. A smaller, but growing contribution is made by the late Kharif crop, which is sown around Diwali (anywhere between October and November) and harvested between January and March. This is the crop entering the markets now. Around 10 per cent of the country’s onions come from this season.

A few observations about Indian onions:

- Fresh onions enter the market every year for seven to eight months—majorly from October to May. The demand for the remainder of about five months starting June to September or October is largely met from stored onions.

- Due to their low moisture levels (crops sown in monsoon months have high moisture levels and thus relatively lower shelf life), the Rabi crop enters storages and feeds the country for the five months mentioned above, or till the next big crop enters the market in October or November.

- Three states, namely Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka, supply about 60 per cent of India’s onions.

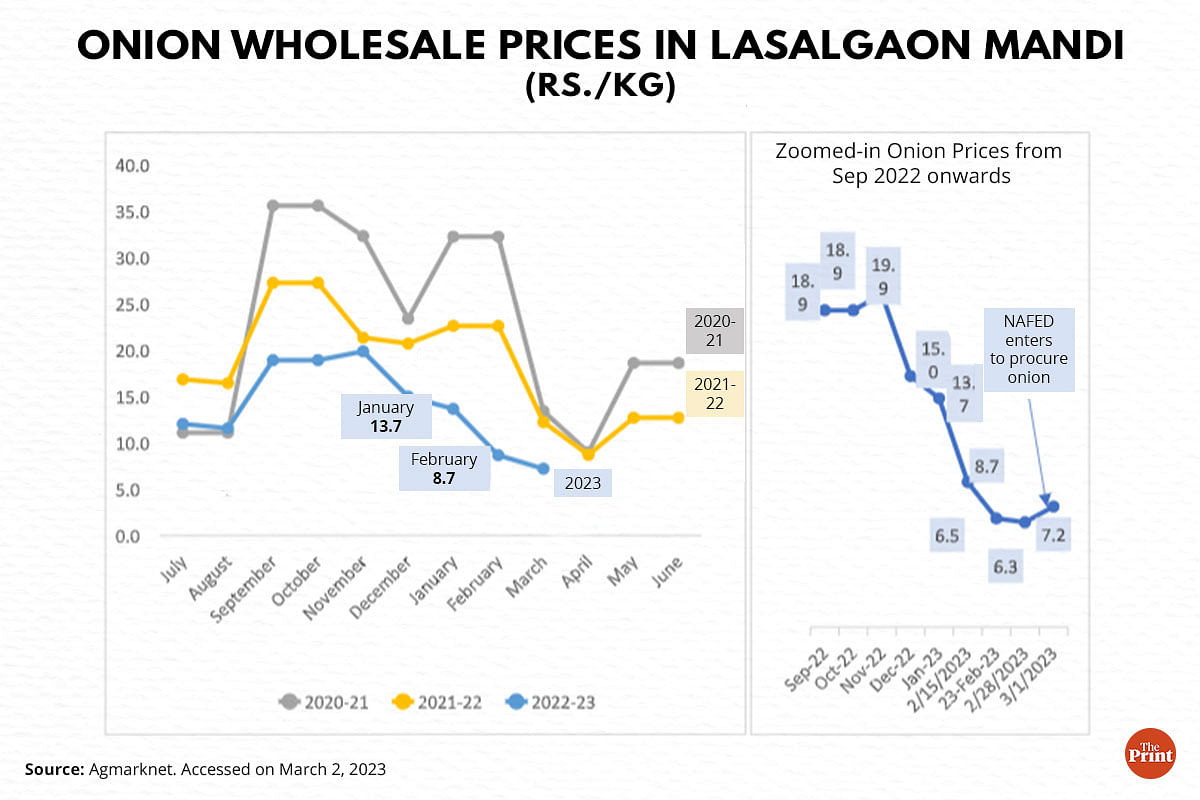

- There is seasonality in onion prices. In an average year, onion prices are generally their lowest between March and June and begin to increase after that. Depending on the size and condition of the stored Rabi onions—which sometimes get affected due to rains—and situation of upcoming Kharif crop, onion prices usually peak around September or October when the stored crop is at its lowest (Figure 1).

- Like many other crops, onion farmers too have been observed to be responsive to prices. Better prices encourage onion acreage, and lower prices shift it to other more remunerative crops. The swing area is studied to be anywhere between 10 to 15 per cent. This makes the pattern of onion glut and deficits almost predictable and inevitable.

Figure 1: Onion wholesale prices in Lasalgaon Mandi (Rs./kg)| Source: Agmarknet. Accessed on March 2, 2023

Figure 1: Onion wholesale prices in Lasalgaon Mandi (Rs./kg)| Source: Agmarknet. Accessed on March 2, 2023

Big Rabi glut

What happened to onions this year? The analysis for this may begin from the last year’s rabi onion crop (sown in December 2021/January 2022 and harvested around March/April 2022). Compared to a normal average of about 10 lakh hectares, the area stood at about 11.7 lakh hectares. Buoyed by good yields, Rabi onion production reached about 23 million metric tonnes by April 2022 compared to a normal of about 19 million metric tonnes. This beefed-up onion stocks, resisting any upward price pressures in the year. With good subsequent crops of Kharif and late Kharif, which are now arriving, onion prices have been falling, particularly since November 2022. (Figure 1). They reached their all-time low in February 2023 with the arrival of late Kharif. Therefore, the situation of glut in onions can be traced to last year’s Rabi season. Thankfully, Indian onions today are globally price competitive, and the trade has access to remunerative markets abroad. This has somewhat restricted the free fall that this year’s onion crop would have met with otherwise.

The problem is not just about this year. It is about the intrinsic structural character of crops like onion, which have a lower shelf life and the demand for its processed products is limited.

Additionally, onion’s cropping, as said before, is cyclical. If prices are high, the farmers expand the acreages. Unless there are damages caused by pests or weather vagaries, higher acreages yield good crops, pulling down market prices upon harvest. And lower prices discourage the next cycle’s acreages pushing down the crop size and increasing prices. And this cycle continues over years.

Also read: Onion export ban is not the answer — it hurts farmers & India’s image as a reliable exporter

Cure for onion tears—access to information

Farmers need access to credible market and price intelligence. Timely access to information about market prices in the neighbouring districts, mandis, or neighbouring states empowers farmers about their decision to sell. Audio or typed messages in local languages, received over his normal or smartphone, could be free or on subscription mode, can provide him with vital price information enabling them to decide the location and quantity of sale.

In case a farmer chooses to defer his sale, access to storage becomes critical. He would need affordable storage and credit to continue meeting his expenditures. Despite the exceptional success of the government’s initiative to expand Kanda chawls (on-field onion storage structures) and the large flow of venture capital funds to start-ups, there has not been any success in developing storage technology for Kharif and late Kharif onion crops. Ultimately, the solution will emerge from a technological breakthrough.

Another low-hanging intervention is rationalisation of the intermediary costs and connecting farmers directly to consumers wherever possible. The start-ups in the field have certainly not achieved as much success in doing so. The retail onion prices in Mumbai and Delhi continue to be Rs 27 and Rs 23 per kg while the farmers in Lasalgaon get only about Rs 7 per kg.

Can Indian consumers be nudged or guided towards increased use of dehydrated onions? By encouraging demand for processed onion products, both farmers and consumers are likely to benefit from production and price stability.

The government created a Price Stabilisation Fund (PSF) in 2015-16 to address problems like the current one. The fund can be used to purchase agricultural produce even if it is not covered under the Minimum Support Prices (MSP). Not only that, the PSF enables the government to purchase a commodity at the market price, which could be higher than the MSP. In this case, the market price is already so low that such interventions become unremunerative.

Like NAFED, Small Farmers’ Agri-Business Consortium (SFAC) has also been nominated by the government in the past to purchase onions. The state governments have been enabled to set up their own PSF. But the officers are reluctant to purchase a commodity if it is not covered by MSP. The procuring agency has suffered losses in the past and due to fear of objections by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) and the threat of enquiry, there is a reluctance to buy from the open market.

The government has a distribution mechanism only in a few metropolitan cities. In Delhi, for example, onions have been sold in the past through Mother Dairy booths. Similar institutions do not exist in most other states.

Unless more medium- to long-term measures are deployed, onion tears would haunt everyone- from farmers to consumers, almost with a predictable certainty every few years.

Shweta Saini is an Agriculture Economist and Co-founder of Arcus Policy Research and Siraj Hussain is a former Secretary to GOI.Views are personal.