India imports approximately 13 to 14 million metric tonnes of edible oils every year, accounting for about 60-63 per cent of its edible oil consumption. To reduce dependence on imports, the Narendra Modi government has rightly implemented policies to boost domestic production of oilseeds such as rapeseed, mustard, groundnut, soybean, and palm, among others. However, it is a pity that the mustard farmers who heeded this call are now facing distress due to plummeting prices, which have fallen below the minimum support price of Rs 5,450 per quintal.

Why should farmers bear the burden of growing more? We highlight the cyclical nature of India’s agri-markets and the role of government policies that led to the fall in mustard prices.

India’s Mission Mustard

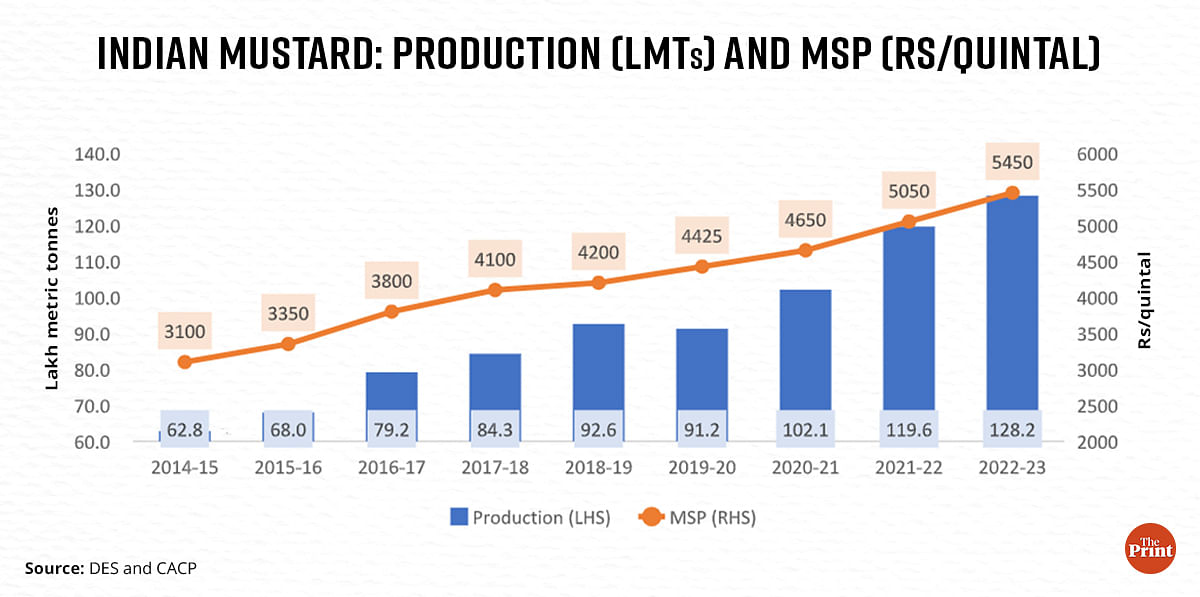

Under the National Food Security Mission-Oilseeds (NFSM-OS) programme launched by the UPA II government in 2007 but implemented only in 2018-19, the Union government has taken multiple initiatives to promote domestic oilseed production. For instance, in the case of mustard, the government significantly increased the MSP from Rs 4,200 per quintal in 2018-19 to Rs 5,450 in 2022-23. Additionally, it promoted the establishment of seed hubs, distribution of certified seeds, timely access to crop advisories, and access to training and demonstrations. Private sector organisations such as Solvent Extractors Association (SEA) and Corteva started their own initiatives. The SEA started its own mustard project 2020-21 with 400 model farms in Rajasthan, which later spread to Punjab and other north Indian states. Corteva has also been working with mustard farmers to improve productivity.

Figure 1: Indian Mustard: Production (MMTs) and MSP (Rs/quintal)

As a result, from an average of 6.3 million hectares of sown area over the last five years, mustard acreage increased by 49 per cent in December 2022 — to 9.4 million hectares. As per the Government of India’s (GoI) second advance estimate, mustard crop production is estimated to be about 8.6 lakh metric tonnes (LMTs) higher than last year (128.2 LMTs in 2022-23, against 2021-22’s 119.6 LMTs).

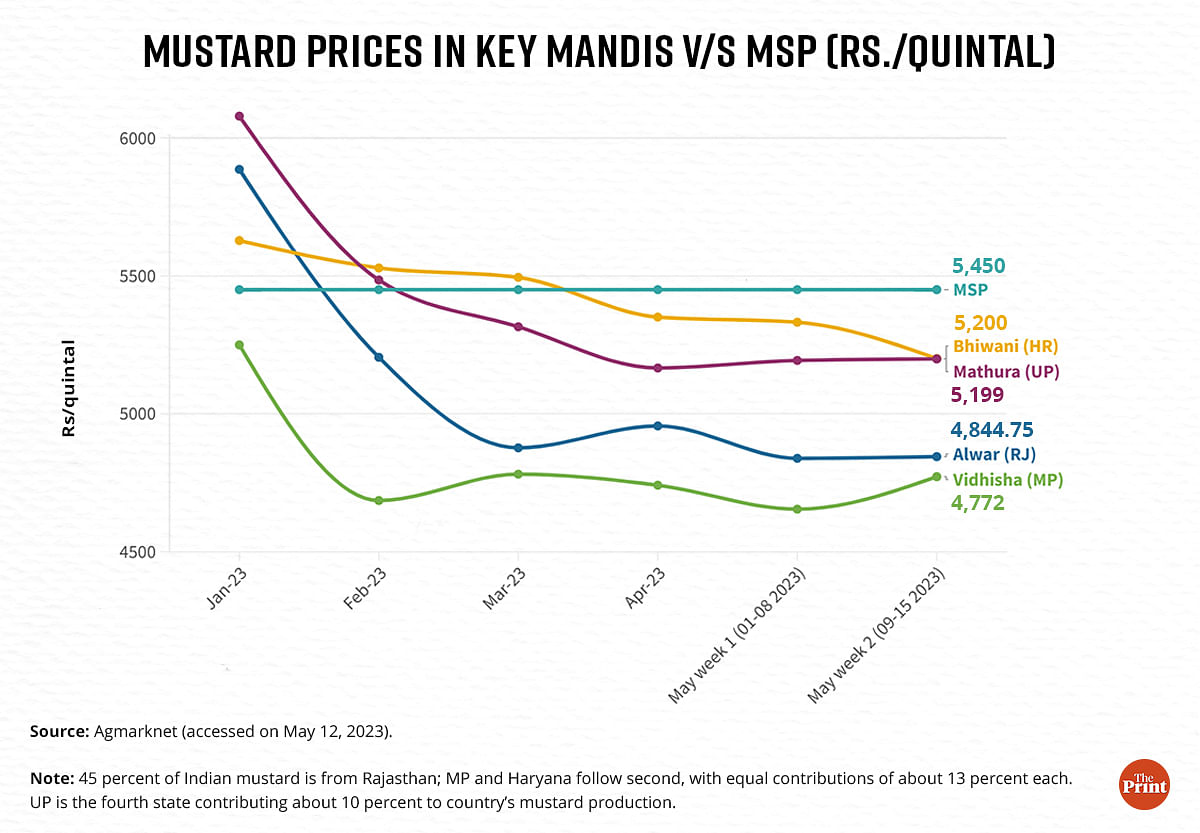

Since February 2023 when arrivals of the new mustard crop began, up until last week, prices in all key mustard mandis ruled below the MSP (Rs.5450 per quintal). Prices in Rajasthan (largest mustard producer in country) trailed MSP by Rs.605 per quintal in the second week of May 2023.

Figure 2: Mustard Prices in Key Mandis v/s MSP (Rs/quintal)

Also read: Food inflation below 6% but average Indian still hurting. What explains the disconnect

The policy effect

An interesting mix of GOI policies can be traced to the current price situation of mustard crop. One is a set of policies that the GoI undertook to support mustard farmer yields and incomes, and the other, almost parallel to these measures, are initiatives that ensured that domestic prices of edible oils and oilseeds stayed low. From Figure 2, it appears that the latter set of policies is dominating the scene. We elaborate on these policies below.

The Union government is supporting mustard farmers by increasing MSP, providing quality inputs, and, most significantly, approving the environmental release of GM mustard — all with a promise to improve mustard yields in the longer run. On the farmer income front, the government responded to falling mustard prices this year by directing the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (NAFED) to procure mustard at MSP. As of 15 May 2023, NAFED had procured about 5.4 LMT of mustard (about 4.2 per cent of the 128 LMT of crop). It is another thing that despite procurement, mandi prices continue to trail MSP.

Mustard is one of the most important oilseed crops in India, and government policies for other oils and seeds have a direct bearing on the crop.

During 2021 and 2022, there was a worldwide crisis in edible oils’ production and trade. Indonesia imposed restrictions on exports, the Ukraine war impacted global value chains, and palm oil was increasingly being diverted for producing biodiesel. Due to India’s heavy dependence on imports, fallouts of these events were felt in the country — edible oil inflation rates shot up to double-digits. The government immediately responded by lowering the import duties of most oils and allowing duty-free import of 2 MMTs of sunflower and safflower oil each under tariff rate quota.

All this resulted in large imports of these oils.

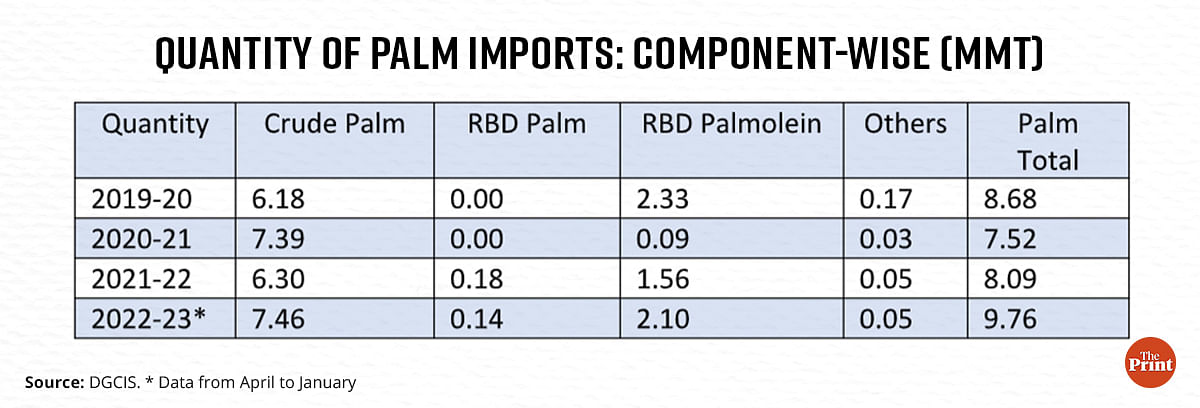

Palm oil, particularly, is an interesting case. At the peak of global palm oil prices, import duties, including cess, on crude palm oil and RBD palm olein were reduced to 5.5 and 13.75 per cent, respectively, in May 2022. In 2018-19, these figures stood at 44 and 54 per cent. But as global palm oil prices eased over time and duties stayed low, cheaper global palm oil imports flooded the country (Table 1).

Table 1: Quantity of Palm Imports: Component-wise (MMT)

On 10 May 2023, the government provided another round of tax exemptions to facilitate cheaper imported crude soybean and sunflower oils.

Even though there is no direct substitution between oils, excessive availability of one variant, say the cheaper palm, encourages its adulteration across other oils, pulling down their prices, and demand for oils like mustard oil.

Also read: Ethanol blending crucial to cut oil imports but doubling it will hurt India’s food…

Four problems

Among other things, there emerge four immediate problems in this case.

First is the agility in policy decisions. Import duties on edible oils, mainly palm, were lowered in May 2022 when global prices were high. Now, those prices have nosedived, but the import duties continue to stay low. While the government is trying to protect the interest of consumers, it must look after the needs of farmers too.

This brings us to the second problem — consumer bias in governmental policies. To ensure lower prices for consumers, policies on storage and trading of key agri-commodities are many times nudged against a farmer. In this case, the low landed price of imported oils has pulled domestic oilseed prices below MSP.

Open import of edible oils prevents any credible assessment of the expected scenario of market prices, and this is the third problem. Due to the ban on the future trading of mustard and soybean, farmers and traders in India are unable to predict the prices for upcoming kharif crops. Market predictability and policy stability are key to the growth of any market.

The fourth problem is the often-cited cyclical nature of agri-markets. There has to be a way to store, process, and trade the surpluses so that farmers make remunerative returns for their good crop performance. Mustard is one such crop this year. Onions and potatoes are other key crops that suffer from such cyclicality every 2-3 years.

What now?

Indian crop production basket needs to be diversified not just to ensure an efficient use of its scarce resources of water, soil, and land, but also to feed the country’s average consumer. If the GOI on the one hand encourages diversification of crops, but on the other hand is unable to protect the incomes of the very farmer who heeds its advice to grow more, then it is not just doing injustice to the farmer but also to its own future plans and vision. Only if the farmer is able to earn remunerative incomes can one expect to trigger a sustainable change in country’s production basket. Otherwise, it is as if we move one step forward and then come back a step, with the next result of not moving at all.

Saini is an Agricultural Economist and Hussain is Former Secretary, GOI. Saini and Suri are with Arcus Policy Research. Views are personal.