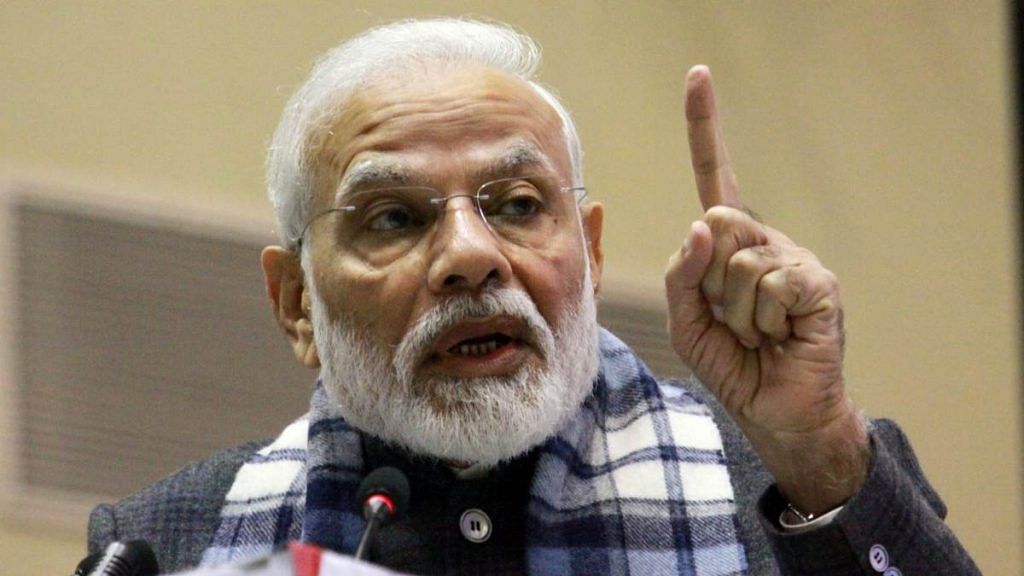

The dramatic changes that the Narendra Modi government has made to India’s citizenship laws is roiling the country. While the domestic-political implications of these policies are clear, the international implications are less so. There are good reasons to expect that negative fallouts will be limited. But there is also the very real danger of hubris and overconfidence in India’s power to handle these challenges.

As others have pointed out, the immediate difficulties are likely to be in India’s relations with Bangladesh and Afghanistan, both of which are named in the recently passed Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Both have been good friends and look to India for support. This has gotten the governments of Ashraf Ghani and Sheikh Hasina in trouble domestically, with their political opponents castigating them as Indian stooges. Both countries are also critical to Indian security, and Indian governments have assiduously wooed them. The task becomes harder now, especially with China waiting in the wings.

Also read: Modi govt’s adamant stand on citizenship will push India’s neighbours into China’s arms

Muted international reaction

In the broader setting, though, the implications are less clear. Domestic behaviour, even egregiously bad ones, often have little impact on how countries behave towards each other. Nations may not like the way another nation treats its people and they may even criticise it – like they did when India scrapped the special status of Jammu and Kashmir – but they often do little beyond that, unless there are other strong political or security reasons for them to take action. This is why the muted international reaction, especially from the Muslim world, to China’s atrocities on Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang province is not much of a surprise.

But also note that this varies according to both a country’s power and its importance to others. Stronger countries can generally expect to get away with behaviour that would have graver consequences for weaker ones: don’t expect leaders of any major powers to see the insides of the Hague Tribunal for war crimes. Equally, some countries are valuable to others as allies – sometimes just because of their location. Pakistan is a good example of the latter.

It is possible that both of these reasons will limit any negative international response to the Modi government’s recent actions. India is now a relatively powerful player in Asian and global politics and this by itself could persuade others to ignore India’s domestic troubles. Additionally, India is now sought after as a balancer to China both by smaller Asian powers and the US, which should also dissuade others.

Also read: Ahead of 2+2 talks, 3 major US dailies put India’s anti-CAA protests on front page

India’s hubris

India, however, also faces the very real danger of over-confidence. Indian leaders have often exaggerated the nation’s power and influence – from the 1950s to unfortunately even now. There can be little doubt that India has grown stronger, but unlike China, it is not a major trading power that has the capacity to punish its trading partners for political reasons.

India’s refusal to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), even if with good reasons, actually reduces its clout by potentially limiting its trading power. And despite the size of its military and its nuclear weapons, it has little capacity to reach much beyond its borders. Closer to home, India in the last two decades has become relatively weaker vis-à-vis China, something that is unlikely to change in the near future.

India may also not be as important or indispensable to others as much as it thinks it is. Sure, the US has invested heavily in India, despite Indian coyness about partnering with the US. American proponents of US-India partnership have suggested that the US should help strengthen India because a stronger India will represent a natural balance to China and thus indirectly benefit the US. But there are growing doubts about the partnership in the US, and even its strongest proponents are no longer as sanguine.

Moreover, these doubts are rising at a time when the foreign policy consensus in the US is increasingly questioning US’ global commitments. President Donald Trump may express his distaste for most US alliances somewhat crudely, but an increasingly popular US foreign policy view is that the US should let allies do their own balancing and America should only step in if allies are unable to do so. Such offshore balancing approach is what an adviser to former President Barack Obama characterised as ‘leading from behind’, a lineage that suggests that the idea has more bipartisan legs and intellectual heft than is usually recognised in India. If American strategy moves in this direction, it could easily flip the earlier logic: the US need not go out of its way to support New Delhi because India has little choice but to balance China anyway. This has obvious implications for how much leeway India has on other issues, including domestic politics.

Also read: Modi govt is obsessed with exercising power instead of focusing on what matters — economy

Dependability

India’s confidence in its attractiveness to smaller Pacific powers should also not be taken for granted. They are unlikely to be thrilled about India’s waffling on both trade and balancing China.

New Delhi often complains about others’ undependability, but it needs to worry about whether this applies to India itself. Even if none of this matters in this particular instance, it will not be a bad idea to become a bit more realistic about India’s power and indispensability.

The author is professor in International Politics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Views are personal.