The brutal killing of Lakhbir Singh, a Dalit who was lynched by a few Nihang Sikhs in Delhi for allegedly desecrating the Sikh holy book, is a firm reminder that we do not have any principled position on religious fanaticism.

Although this event was overwhelmingly criticised, the manner in which the ‘sacredness’ of religious scriptures is invoked by our political class is highly problematic.

A strong impression is created that religious symbols — cow, holy books, places of worship — are as important as human life. Hence, they should be protected by the State as rights-bearing citizens. The calculated response of major political parties, especially in Punjab, in the Lakhbir Singh episode, underlines this emerging political consensus.

Three key questions associated with this case are important. Is it possible to compare the life and liberty of an individual citizen with any religious book? Do holy books and religious relics, which are supposed to be guarded by the ‘Almighty God’ (or Gods), really need human protection? If yes, what is to be done with irrational and outdated religious practices propagated by holy books?

Also Read: Communal violence in the time of Modi has a distinct shade. Here’s why

Holy books vs unholy citizens

I do not want to invoke the typical ‘freedom of expression’ argument. Instead, we must trace the processes that contribute to pro-religion politics.

In 2018, the Punjab Legislative Assembly passed the Indian Penal Code (Punjab Amendment) Bill. The law amends Section 295A of the Indian Penal Code by introducing a new sub-section 295AA, that is applicable only in the state of Punjab.

According to this new sub-section, “whoever causes injury, damage or sacrilege to Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Srimad Bhagavad Gita, the Holy Quran and the Holy Bible with the intention to hurt the religious feelings of the people shall be punished with imprisonment for life.”

There are two crucial aspects of this new law: the act of ‘sacrilege’ and the ‘intention’ of a person. These are highly subjective matters, which are subject to official/judicial interpretations. There cannot be a universally applicable parameter to determine the exact meaning of these terms.

In any case, this legal fluidity gives immense powers to the police as well as the religious elite. Any deviation from the standard religious practices/customs defined by the dominant religious establishment as reverential or sacred could become ‘desecration’ or ‘disrespect’.

This legal framework, however, seems to offer a privileged status to religious scriptures. The provision of life imprisonment in such cases clearly indicates that the protection of a holy religious book is comparable with the right to life given to a citizen.

The statement made by Akal Takht jathedar Giani Harpreet Singh seems to reiterate this point. He does not make any comment on the brutality of this event. Instead, a narrative of Sikh victimhood is presented as an argument to justify the legally protected status of the Sikh holy book.

He says, “there is a background to what happened at Singhu as more than 400 incidents of sacrilege have been reported in the last five to six years…there is nothing above the Guru Granth Sahib for Sikhs. But how sacrilege incidents are being reported and accused are often termed mentally ill to avoid the unfolding of conspiracy have hurt the confidence of Sikhs in the law and justice system.”

Also Read: Stop looking for scientific discoveries in holy books, be it the Vedas or the Quran

Spiritual vs religious

Giani Harpreet Singh’s emphasis on Sikh sentiments reminds us of the late 1980s controversy on Salman Rushdie’s novel Satanic Verses when Muslim clergy also used the same set of arguments to justify their status as the protectors of faith.

Such politically motivated religious assertions, we must note, highlight the fragility of religious scriptures, symbols and personalities. The religious icons are presented in the image of humans as if their survival depends entirely on the mercy of the concerned religious group and its recognised clerics.

All-India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB), for instance, gives an interesting description of ulema class. It strongly argues that ‘…Allah entrusted the responsibility of explanation of divine laws to fuqha (learned).’ (Maulana Syed Shah Minnatul Rehmani, Qanoon-e-Shariat ke Masadir aur naye masael ka hal, (Urdu) Delhi, AIMPLB, 2012, p. 12). Does it mean that a layperson cannot draw their own meanings of the Quran?

This instrumentalist description of the religious scriptures as complex, rigid and stagnant texts, actually goes against the spiritual/philosophical foundations of religious doctrines. Religious scriptures are called ‘holy books’ precisely because of their ability to produce complex philosophical arguments in a simple, straightforward and commonsensical manner.

These sacred books make universal claims and recognise the entire humanity as their intended/interested readers. The religious elite, on the other hand, always undermines this universalism to claim ownership of religious texts and relics. That is why the Bhagavad Gita becomes Hindu and the Quran becomes Muslim.

Also Read: Nihang tradition is rich. Don’t just view them through Singhu killing lens

Holy books and inhuman practices

In any case, it would be wrong to believe that religious scriptures contain the ‘final truth’. These texts are product of a particular historical moment and they are full of inconsistencies and contradictions. Therefore, imagining religious texts as ‘context-free’ is a critical mistake.

Many organised religious establishments in India (such as Vishva Hindu Parishad-supported Dharam Sansad, Akal Takht, AIMPLB, and various Christian organisations) use religious texts to justify inegalitarian practices and customs. The debates on cow vigilantism, ‘triple talaq’ and alleged desecration of the Granth Sahib are good examples of this trajectory.

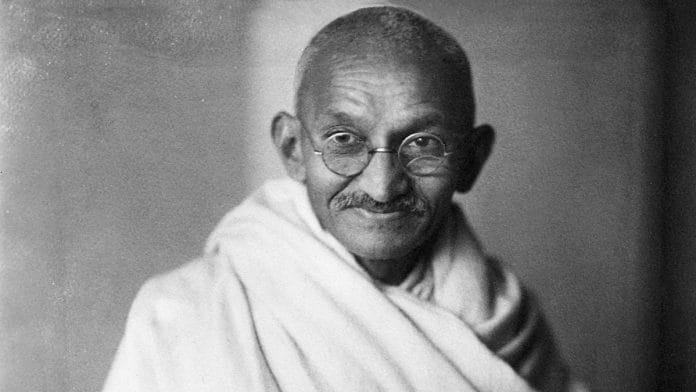

Gandhi, perhaps, is the only public figure in India, who offers us a religious critique of this irrational religiosity. In 1925, when two Ahmadiyya Muslims were lynched and stoned to death by a section of Muslims in Afghanistan, Gandhi wrote, “I understand that the stoning method is enjoined in the Koran…But as a human being living in the fear of God, I should question the morality of the method under any circumstance whatsoever…this particular form of penalty cannot be defended on the mere ground of its mention in the Koran. Every formula of every religion has in this age of reason, to submit to the acid test of reason and universal justice if it is to ask for universal assent. Error can claim no exemption even if it can be supported by the scriptures of the world.”

Gandhi’s courage and conviction underline a principled critique of irrational and unspiritual religiosity that we experience today. He does not give up what he calls the ‘fear of God’ and makes it difficult for the religious elite to appropriate religion.

Bapu, you are right. We must feel sorry for Lakhbir Singh’s death in the name of God!

Hilal Ahmed is a scholar of political Islam and associate professor at Centre for the Study of Developing Societies. Views are personal.

(Edited by Srinjoy Dey)