Last year, a friend of mine who teaches journalism at St. Teresa’s College, Ernakulam asked me if I knew somebody who might be interested in enrolling for the course. That sounded like a far cry from the glory days of the prestigious all-girls college, when one had to be influential or get top grades to secure admission.

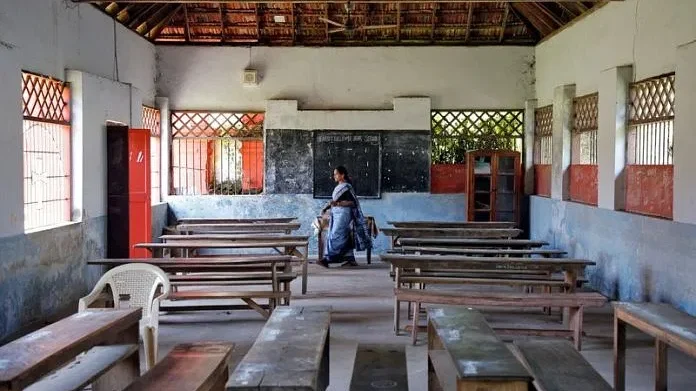

It is not uncommon these days to see prominent institutions putting out advertisements in leading dailies, hard-selling the various programmes they offer. The predicament is not limited to one college or stream. In fact, this is emblematic of the crisis gripping the higher education sector in Kerala.

Student migration has doubled from the state in five years post-Covid-19, the quinquennial Kerala Migration Survey shows. It is not that students from Kerala weren’t pursuing courses abroad in the past, but unlike then, the primary motivation isn’t securing a degree anymore. In fact, most of them are leaving for good—an ominous sign for a state with one of the lowest fertility rates in India.

While migration from Kerala to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries is coming down, there is a huge spike in emigration to the West. A supplement dedicated to the tom-tommed Invest Kerala Global Summit in The Hindu’s Kochi edition had to share space with a half-page ‘Study Abroad’ advertisement—a fair depiction of the predicament the state finds itself in.

Kerala’s predicament

For a state that prided itself on being the trailblazer on many counts, Kerala failed to open itself up in the liberalisation era. In the Marxist scheme of things, private capital and wealth creation were looked down upon. If the first wave of student migration was to neighbouring South Indian states, it was followed by the flight of youth and capital abroad.

It took the Left over three decades to finally wake up and smell the coffee. Only in 2024 did the Budget announcement welcome private universities. But the horse has already bolted.

The mushrooming of ‘Study Abroad’ consultants including fly-by-night operators even in the small towns of Kerala is a testament to the sheer number of students seeking education overseas. If the previous generation left after graduation to do specialist courses and returned to the country, the current lot leaves soon after school to virtually any country offering permanent residency (PR).

This is not only an indictment of the plummeting standards of education in the state, but also a reflection of the dearth of job opportunities and poor resource allocation by successive governments. Once again, the dubious role of Marxists in propagating a model solely reliant on the public sector looms large.

Perhaps people would find it hard to believe that the Left in Kerala opposed computers and tractors once upon a time. The Left’s resistance even to the Public-Private Model (PPP) envisaged by K Karunakaran, as well as their contribution to scuttling the Express Highway project conceived at the turn of the millennium in Kerala needs no retelling.

By the time the Marxists made amends and embraced these changes, the state paid a heavy price for it.

Also read: Kerala has a ghost houses problem, but the state just doesn’t want to get into it

Sociological impact

Beyond the obvious ramifications of brain drain, there are demographic and sociological consequences. The Gulf migration in the past brought handy remittances to the state until the expats eventually returned—as GCC countries don’t offer PR. On the contrary, the emigration of youth is concentrated in the central Kerala districts of Pathanamthitta, Idukki and Kottayam. They’re leaving their elderly parents behind in Kerala to start life afresh in greener pastures.

This becomes more concerning when one takes into account the fact that Pathanamthitta (-3 per cent) and Idukki (-1.8 per cent) have registered negative growth rates in the 2011 census. Kerala is very much in the process of turning into a geriatric society. In some cases, the parents eventually tag along as babysitters, leaving properties behind as dead assets or selling them for a pittance. This has led to falling land prices in central Kerala.

In fact, many central Travancore settlements are at risk of turning into ghost towns with empty houses. As per the 2011 census, 11 per cent of the over 10 million houses in Kerala were vacant. This has gone up to 14 per cent—twice the national average—according to a financial survey published in 2019, and would have gone further up in the post-Covid scenario.

A survey by the Kerala Academy of Sciences revealed that seven out of ten students who flew out of Kerala for higher studies either do not wish to come back at all or are undecided about returning.

Also read: Campus violence eroding Kerala colleges’ standards. Fix this before opening foreign campuses

Creation of jobs

There are no easy solutions to brain drain. However, the first thing Kerala needs to address is the creation of jobs. The state has a large segment of highly aspirational middle class, who often mortgage their property to send their children abroad.

The disruption of Kerala’s agricultural economy through land reforms was a watershed moment when it came to wealth redistribution, but subsisting on agriculture has become unviable on account of small land holdings and the high cost of labour in the intervening years. Especially without a commensurate increase in the prices of agricultural produce.

There is a limit to the number of jobs generated in the government sector. As such, Kerala has a bloated bureaucracy with many redundant posts. The state government fails to redeploy these personnel simply owing to the pressures exerted by the trade unions. And with Kerala on a borrowing spree in the last few years, the state finances are in precarious shape, with capital expenditure taking a hit.

There are sectors like tourism, which can change the game altogether if the government could merely play the role of a facilitator and spend on basic infrastructure such as highways and upgradation of civic facilities. The state of the Fort Kochi beach and the plight of Alappuzha are examples of Kerala’s shoddy approach to the revenue-generating sector, which creates jobs and boosts economic activity even during a downturn.

It is generally argued that Kerala’s ecologically fragile and densely populated terrain with 44 rivers isn’t ideal for heavy and polluting industries and so, even if the state missed the bus on industrialisation, it may not matter much. Be that as it may, Kerala still couldn’t leverage the service sector boom in the last three decades with its abundant human resources.

Despite establishing a pioneering Information Technology (IT) facility like Technopark at the cusp of liberalisation, Kerala failed to leverage it and ceded space to Bengaluru. Kerala may not have a huge metropolis like Chennai, Hyderabad or Bengaluru, but with the IT industry staying clear of malignant trade unions, it is one sector that could assimilate a chunk of the state’s graduating workforce.

For a state that is among the biggest consumers of automobiles, Kerala cannot boast of a major vehicle manufacturer setting shop in the state. It may be pertinent to recall that the day German automaker BMW came to Kerala to initiate talks with then CM Oommen Chandy in 2004, there was a strike leading to its cancellation. And when the second appointment too was cancelled on account of another shutdown, the company opted for Tamil Nadu.

Also read: How the Malayali Gulf migrant became the ‘suffering rich’

Fixing Kerala’s education

Before fixing the business environment, however, Kerala needs to proactively solve the huge crisis in its education sector, starting with schools. It was only recently that the director of general education was heard lambasting the practice of promoting all students regardless of academic ability and lamenting that many of them cannot read or write.

The state of Kerala’s private engineering colleges should have a special mention here. There were 167 professional colleges in the state during the boom in 2001, that number has now come down to 90, with many of them on the brink of shutdown. This is happening when students from Kerala still make a beeline to other states for medicine and nursing admissions, due to a paucity of seats.

The practice of the Kerala state board liberally granting marks to secondary school students possibly even led to Delhi University (DU) changing its admission criterion, in the interest of fairness. It came as no surprise that there was a huge drop in the enrolment of students from Kerala in DU following that. The bane of student politics and ragging in Kerala, which made national headlines recently, must only make more students flee the state.

A majority of female students (78 per cent) choose to migrate seeking a society that promotes inclusivity, and offers a better lifestyle, free from social stigmas and stereotypes – according to a study conducted by the Centre for Public Policy Research. It is only when the youth began to opt for foreign shores that the policy-makers belatedly reacted to the crisis.

There is a vested interest for the Left in propagating campus politics: the Marxist assembly line is sustained today by those signing up for the party in colleges. If universities are meant to be liberal spaces to broaden your horizons, Kerala’s campuses have become notorious for being ‘Marxist fortresses’ where critical thinking becomes a casualty.

Kerala needs to overhaul its educational curriculum and get the industry involved so that more graduates can be absorbed into the workforce. Violent student politics and unionisation of academics—rendering them stooges of political parties—need to be reined in. Only then does Kerala have some hope of turning the tide. The million-dollar question is who can bell the cat? Else, emigration is set to continue—unabated.

Anand Kochukudy is a Kerala-based journalist and columnist. He tweets @AnandKochukudy. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)