In the centuries before European colonies in India, how did the West imagine the East? The answer lies in a dynasty of Mongols who ruled Iran in the 1200s—The Ilkhans, rivals and contemporaries of the Delhi Sultanate.

The Turk rulers of Delhi imported Iranian Muslims to help them rule. The Ilkhans imported Kashmiri and Uyghur Buddhists. And so, as Islam spread East, Buddhism went West. In this last great flowering, India’s once-dominant religion spread as far as Azerbaijan, exciting the imaginations of Iranians, Italians, Germans, and even the English.

Mongols and Kashmir

It’s impossible to overstate how deep, how lasting, North India’s relationship with Central Asia has been—and how much we imagine as purely “Indian” stems from vigorous exchanges with the great grasslands. Central Asian conquerors could certainly be violent, but they were not barbarians: they brought new ideas, engaged with existing traditions, and attracted and drove immigrants in all directions.

By the late 1200s, the Mongol Empire had spread through much of Eurasia. After an initial wave of terror and brutality, Mongols settled down to rule Iran, China, and the lands in between with great creativity. They made repeated attempts to seize the Gangetic Plains, but these were fended off by the Turkic Sultans of Delhi. In Kashmir, they had much more success. The region was devastated by Mongol raiders, who enslaved locals, looted cities, and set up puppet rulers. In the process, they created a political vacuum that allowed for the rise of a new Kashmir Sultanate.

Like all Central Asian conquerors, the Mongols did not let religion get in the way of their conquests. Hulegu Khan (c. 1217–1265), the founder of Iran’s Ilkhan dynasty, was a devout Buddhist, educated in China. Yet in Kashmir, his generals plundered with no regard for the region’s deep Buddhist and Hindu roots. And with no trace of irony, Hulegu later built a Buddhist temple in Malot, in the present-day Punjab province of Pakistan. In 1258, the Buddhist Hulegu brutally sacked the great metropolis of Baghdad, thecapital of the Abbasid Caliphate, slaughtering thousands and destroying perhaps the greatest libraries of the medieval world.

Hulegu eventually set up his kingdom in Iran, where he struggled with an ethnically diverse Muslim aristocracy. Of course, his sacking of Baghdad had not endeared him to them, so he encouraged immigrant scholars and experts to flock to his court. Within a few years, he had representatives of all major Asian religions working for him: Nestorian Christians, Jews, Muslims, and, most importantly for our story, Buddhists from Kashmir and present-day Xinjiang.

Also Read: Brahmins in sultans’ courts, snake-worshipping Muslims— The real story of medieval Kashmir

Rise of Kashmiri Buddhists

By Hulegu’s time, Buddhist leaders across Asia had been buttering up Mongol rulers for the better part of a century. In China, Hulegu’s cousin, Kublai Khan, promoted Tibetan Lamas to high offices and lavished them with gold and silk. Hulegu’s Uyghur Buddhist nobles, as historian Roxann Prazniak writes in Ilkhanid Buddhism: Traces of a Passage in Eurasian History, advised him on medicine, agriculture, and governance. Some Uyghur monks even took breaks from their vows to join him in sacking Baghdad.

Kashmiri Buddhist masters also worked for the Ilkhans. They were a more intellectual and savvy lot.

In the 1270s–1280s, conflicts between the Ilkhans and their cousins in Central Asia reduced Uyghur immigration into Iran. Kashmiris then made their move, encouraging the Ilkhans to construct major Buddhist temples, including rock-cut structures near major Iranian cities like Tabriz. For the first 30 years of Ilkhanid rule, according to The Cambridge History of Iran, nearly half of the treasury was dedicated to setting up Buddhist images. Much of this wealth came from Iran’s position as a trading intermediary between India and Europe.

Kashmiri Buddhists and Iranian Jews formed a tacit alliance at the Ilkhan court, aligning against Iranian Muslims. A later Muslim historian, according to Prozniak (Ilkhanid Buddhism), even claimed that a Jewish doctor of the Ilkhan suggested the Kaaba in Mecca be replaced with a pagoda. Though 13th-century Iranian Buddhism was a conqueror’s religion, it had a receptive audience. As we’ve seen in earlier editions of Thinking Medieval, as late as the 8th and 9th centuries, Iranian nobles still followed Buddhism. Even after converting to Islam, the Buddha was a recognisable figure in Iran. Central Asian Muslims had long written about Buddhism in Arabic texts, describing him as a prophet.

Also Read: ‘Kingdom Come: Deliverance’ to ‘Total War’, how video games make medieval history memorable

How Buddhism influenced Iran

Ultimately, though, Iran’s 13th-century fascination with Buddhism did not last. The Ilkhans converted to Islam, and the court’s Buddhist experts gradually migrated. But Buddhism left deep, surprising traces.

From 1307–16, the Ilkhanid vizier Rashid al-din, an erudite scholar, wrote a new history of the Islamic world, in which Buddhism played a central part. As a loyal courtier, Rashid al-din had to explain how the Mongol Ilkhans had been able to wreak such havoc but were now good Muslim kings. He also had to explain Iran’s long Buddhist history, and the recent—if brief—revival of that ancient religion. To do this, he worked closely with Kamalashri, a Kashmiri Buddhist who had migrated to Iran.

Kamalashri had an interesting job: he had to explain Buddhism’s over 1,500-year history and summarise its many intellectual strands while also remaining employed in a Muslim-dominated Mongol court. His solution was to claim that the Mongols were descended from Indian kings, including the Kashmiri ruler Harsha (r. 1089–1101). He explained Indian religions as having been founded by many “prophets”: Shiva, Vishnu, Brahma, and, most importantly, the Buddha, who was superior to the rest due to his humility and nonviolence.

Rashid al-din took this idea and ran with it. Arabs, he said, were originally Buddhists before receiving the revelation of Islam, which rendered Buddhism obsolete. And because the Mongols were descended from Indians, who had received the prophet Buddha, they had a semi-divine right to rule—at least, more than the Mamluk (slave) dynasties of Egypt, their rivals.

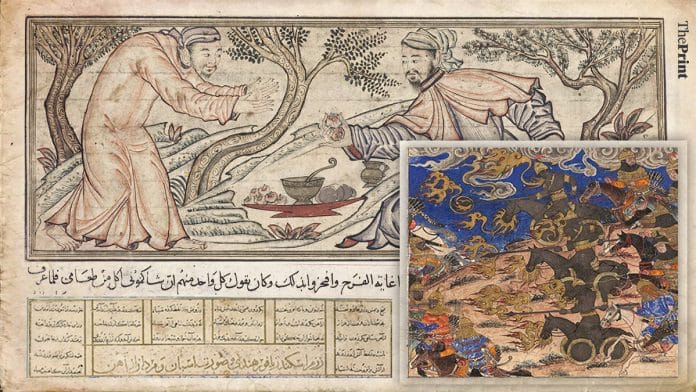

Rashid al-Din also paired his history with illustrated scenes from the Buddha’s life, depicting him as a bearded, robed Sufi mystic. He argued that thisBuddhist precedent also explained the Ilkhan’s eclectic approach to religion, even after converting to Islam. Though they converted their former Buddhist temples to mosques, the Ilkhans otherwise insisted on treating all religions in their territory equally. But unlike Rashid al-din, medieval Muslim fundamentalists—only recently traumatised by the Ilkhans’ destruction of Baghdad—saw all this with suspicion, a sign of lingering Buddhist “heresy”.

That’s not all. The Ilkhans had close diplomatic and commercial ties to Europe, and Europeans viewed them with fascination. Through Persian and Arabic translations, as well as European travellers encouraged by Mongol peace, Buddhist stories spread far, far West. Marco Polo, for example, wrote with admiration of “Sakyamuni Burkhan”, and his 84 reincarnations as animals and finally a god—a garbled version of the Jatakas. Stories of the Christian Saint Eustace reflect some Buddhist values: nonviolence toward animals, and vegetarianism. Indeed, as Prozniak writes (Ilkhanid Buddhism), charity toward animals became increasingly admired in the Muslim world after the 13th century, possibly a result of that last brilliant flowering of Buddhism in the West.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)