M. Karunanidhi always acknowledged his followers in his speeches, and said, “My siblings are more dear to me than life”.

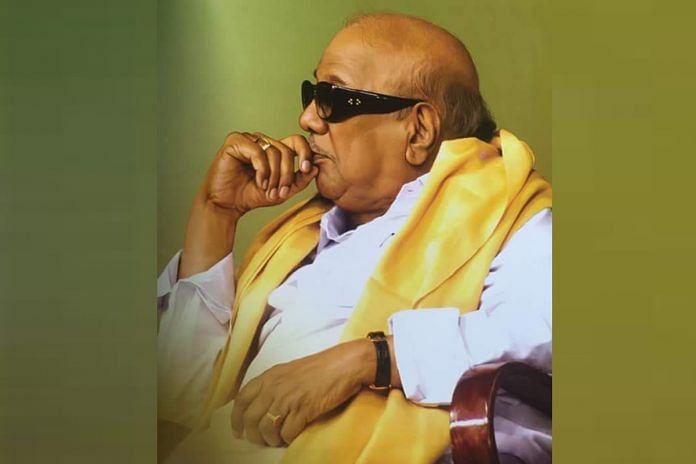

When asked in an interview what he would like inscribed on his tombstone, M. Karunanidhi is said to have quipped: “The tireless worker rests here (ஓய்வரியா உழைப்பாளி இங்குஓய்வெடுக்கிறான்)”. By all accounts, the iconic Tamil leader was a workaholic. He scaled heights in politics, literature, and cinema. His oratory was unmatched; his writing will be unrivalled. However, it is his political feat of winning all 13 legislative assembly elections that will probably never be eclipsed.

Kalaignar, as he was known to his loyalists and rivals, lived and breathed politics. His party, its ideology and the cadres – whom he addressed as siblings – meant everything to him. He would often say that the DMK cadres were only born to different mothers for it would have been impossible for one womb to bear so many children. He thus began each letter with his trademark “anbulla udanpirappey (dear sibling)”.

During every public meeting, there would be pin-drop silence when it was his turn to speak. In Tamil Nadu, it is customary to acknowledge the leaders and speakers on the dais at the beginning of one’s speech. Kalaignar always followed this stage protocol, but his opening sequence would conclude with his trademark phrase acknowledging his followers as “my siblings who are more dear to me than life (என் உயிரினும் மேலான அன்பு உடன்பிறப்புகளே)”. The crowd would always reach a rapturous crescendo by the time he uttered these words, and this set the tempo for all his speeches.

Also read: The eternal flame of Dravidian politics is extinguished. Farewell, ‘Kalaignar’ Karunanidhi

Although rhetoric was prolific in his written and spoken word, Kalaignar was a pragmatic and effective politician. Under him, Tamil Nadu perfected the Dravidian economic model of consumer socialism. He gave impetus to industry by setting up the first industrial mega-estate in Ranipet spread over 730 acres, birthing 107 new industrial plants, in 1973.

His fourth and fifth terms as chief minister, in 1996-2001 and 2006-2011, saw the development of Tamil Nadu into an information technology hub and an automobile manufacturing powerhouse. The number of check-dams and universities built under the DMK regimes far surpasses that of other parties, which have governed the state. The state has performed better than the national average in all economic and social indices over the last four decades.

It was the cause of social justice that was closest to his heart. During his first term as an MLA, he raised issues pertaining to land rights of agricultural labourers in Nangavaram. When he became the chief minister, he legislated the removal of hereditary priesthood in Hindu temples. He championed sub-divisions within reservation quotas and promoted a casteless society through multi-caste government housing (the Samathuvapuram scheme).

During his final term as the chief minister, he oversaw the setting up of a welfare board for transgenders six years before the landmark Supreme Court judgment in the NALSA vs Union of India case. Similarly, the state government’s insurance scheme for life-saving treatments predated Modicare by eight years. Tamil Nadu was, thus, always ahead of the social policy curve.

Also read: M. Karunanidhi had declined to be prime minister saying, ‘I know my height’

It was, however, his love for Tamil that has been his constant companion throughout his life. When the first wave of Hindi imposition under the newly elected Congress government hit erstwhile Madras Presidency in 1938, 14-year-old Kalaignar had led mini-protest marches, screaming “Let’s go to war if needed, to chase away this Hindi ghost; Let’s remind this Hindi witch, this is not a land of cowards (வாருங்கள் எல்லோரும் போருக்கு சென்றிடுவோம் வந்திருக்கும்இந்திப் பேயை விரட்டி திருப்பிடுவோம், ஓடி வந்த இந்தி பெண்ணே கேள், நீதேடி வந்த கோழை உள்ள நாடு இது அல்லவே)”.

In June 1953, the four-year-old Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) party organised protests against the use of Hindi names for towns and villages in the state. Kalaignar would lead the protest to change the name of Dalmiapuram train station to its original Tamil name – Kallakudi – by laying his head down on the railway platform. In later years, he played a major role in persuading the Government of India to recognise Tamil as a classical language and set up the Central Institute of Classical Tamil in Chennai.

The love between Kalaignar and Tamil was mutual in some ways. The rich language and its flowery prose helped Kalaignar rise as the state’s unparalleled political giant; in return, he repaid his debt to the language in full. When asked what his regret as a politician was, he was able to admit that his efforts to make Tamil an official language of the Union of India and the lingua franca of the Madras high court had not yet borne fruit. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that he lived his life true to the famous Tamil proverb:

உடல் மன்னுக்கு.

உயிர் தமிழுக்கு.

The body is buried in the sand.

But the soul is dedicated to Tamil.

Manuraj Shunmugasundaram is an advocate and DMK spokesperson.