Congress will say it got about as many votes as the BJP in Karnataka but still lost on seats big time. Fact: In the ‘First Past The Post’ system, more important than how many votes you get is where you get those votes. That is electoral science, and Amit Shah is its new master. Fifty years after Kamaraj, he’s the first truly powerful chief of a ruling party.

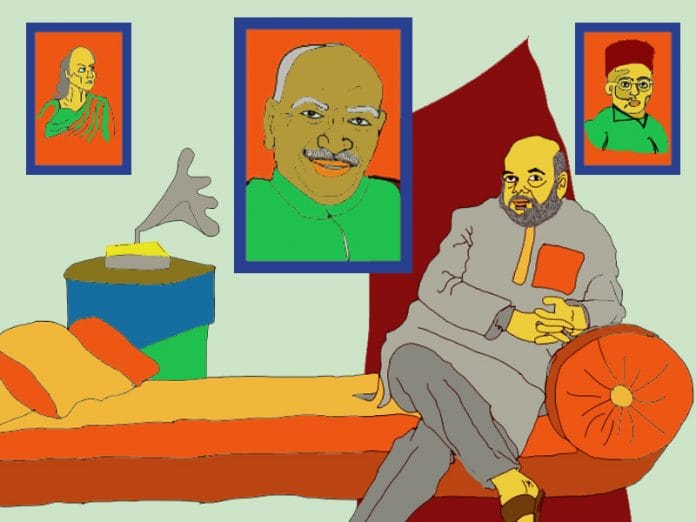

The living room in BJP president Amit Shah’s residence has minimalist furnishings, like the homes of old-generation politicians. He speaks to visitors from his favourite spot on the middle sofa, his back to the wall. A visitor notes the two framed portraits on that wall: Chanakya or Kautilya to the left of your eye, and Savarkar to the right. Those two deities determine his politics — Kautilya for political craft, and Savarkar for his ideology of Hindutva-nationalism. Both would feel vindicated by the Karnataka verdict.

Shah could, however, add a third portrait to that wall, ideally in the space between Kautilya and Savarkar. It would have to be a pucca Congressman. Because while his political and state power, and philosophical impulse, comes from the two already there, his political style and authority over his own party harks right back to the heyday of late Congress president (1964-67) K. Kamaraj. Not since Kamaraj had cabinet ministers trooped into the ruling party president’s office, to read their own report cards, or offering to resign to devote time to party work. Or report to him the morning after their promotion, as Piyush Goyal did Tuesday after he was handed temporary charge of the finance ministry during Arun Jaitley’s recovery period.

Not since Kamaraj in his first reign has a full-time ruling party president wielded such power. I am not quite sure even Kamaraj campaigned in elections as much as Shah does, but perhaps he didn’t have to. Elections in his heyday were a single-horse race. For clarity, we are only talking of full-time party presidents, as different from Congress Prime Ministers who were also party presidents or a party president who had an “appointed” Prime Minister with limited powers.

Other full-time ruling party presidents like Dev Kant Barooah, Chandra Shekhar (Janata), and those who held the same position in the BJP during the Vajpayee years had limited powers and therefore, do not make the cut. Of course, many would rightly point to differences between Kamaraj and Shah. The former had been a chief minister and a grassroots leader who left his imprint on many social programmes that still endure. But no two persons are alike, and our comparison is sharply focussed on pre-eminence within the party.

Shah’s power is more unique because Narendra Modi doesn’t owe his rise to him. It is the other way around. Shah was Modi’s personal choice as party chief after he became Prime Minister in 2014. You can search hard, with the highest degree of suspicion as medical pathologists like to say, but it isn’t possible to see an issue where he may have worked at cross-purposes with the Prime Minister. Nor is there evidence yet of his having been overruled or a decision thrust on him.

Just what were they smoking, drinking, eating, thinking, when they did so?” I had asked in a National Interest in July 2013 when the BJP made him in charge of their UP campaign for the general election. For sure, I was proven wrong, as he delivered 73 seats (including two with allies) out of UP’s 80. The reason, in retrospect, was an assumption I made erroneously: that the BJP once again wanted to build an NDA government in the image of Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s. That the party’s approach would be inclusive, soft Hindutva, without upsetting the centrist status quo. The conclusion about Shah being a bad choice for UP was only going to be correct if that belief was true.

As politics unfolded, I was proven unwise to make that assumption. Subsequent politics has further underlined how wrong it was of me. Far from building one more government in Vajpayee’s image, the Modi-Shah view was to build a “genuine” and unapologetic BJP-RSS government. There was also an understanding that Vajpayee’s government was hardly the BJP’s as a large number of key ministries were with non-RSS people. It doesn’t just apply to ministries given to allies like George Fernandes (defence), but also to Jaswant Singh, Yashwant Sinha, Rangarajan Kumaramangalam, Arun Shourie and others, who were not ideological natives of the RSS and the BJP.

That government is now seen to have been true neither to ideology nor the party. The current dispensation belongs to the other end. Where the party doesn’t have talent for a job with requisite ideological purity, it is no longer willing to explore outside to find it. The party would give power only to the absolutely pure, or those who have paid their dues through the decades. This has been driven unforgivingly by Shah.

This BJP/NDA government, in that sense, is completely different from the earlier one. That the BJP now has a majority of its own and rules most of our states makes it easier, but you can be sure if L.K. Advani, or other older BJP leaders Delhi is familiar with, had been given this majority, they would not have built a government with such uncluttered ideological commitment.

Modi underlined this with his choice of RSS pracharaks and a young faithful as chief ministers of Haryana, Jharkhand and Maharashtra, though they were political lightweights. Shah then moved in with his preferred choices — Vijay Rupani in Gujarat, Yogi Adityanath in Uttar Pradesh, and Ram Nath Kovind as President of India. These were not in defiance of the Prime Minister; just that the initial choice was made by Shah who kept each secret from the party.

On Gandhi Jayanti in 1963, Kamaraj caused a political upheaval by resigning as Tamil Nadu chief minister, to rededicate himself to party work. In his wake, six cabinet ministers and five other chief ministers resigned too. It saw heads like Morarji Desai and Jagjivan Ram roll. His was a brutal internal clean-up, and was called Kamaraj Plan, though he wasn’t even the party chief yet. It has faded from memory now, but it was for long a storied purge of Stalinist dimensions, though bloodless and “voluntary”. It kept political cartoonists and satirists busy for a long time. Nehru, then in decline, was so impressed (and possibly insecure) that he asked that Kamaraj be made party president. He came to his elements after Nehru’s death, ensuring the swearing-in of Lal Bahadur Shastri first and Indira Gandhi next, destroying the ambitions of well-entrenched Morarji Desai. During these years, 1964-67, the most powerful Congressmen chased him for favour and his fabled reply “paarkalam” (let’s see) in Tamil joined India’s political dictionary.

We don’t yet know if Shah has such a favourite line, but the rest of the Kamaraj playbook is all there. Ministers line up before him, not the Prime Minister, who has given him this power. And he would persuade them to “volunteer” resignations to rededicate themselves to party work. They will all come out smiling, claiming to be loyal party workers with no other expectations, even as their hearts bleed. They work on presumption now that the Modi-Shah leadership will continue until 2024 and grow more clout as time passes. They would keep hoping that Shah notices their contribution to party work and brings them back at some point.

Shah has also brought a talent for numbers, alliances and unabashed commitment to the concept of “winnability” as the final and unassailable element of his electoral politics. As the BJP’s success in the Hyderabad-Karnataka and Ballari region shows, it works. BJP’s critics blame all of its victorious runs on communal polarisation and “ideology of hate”. Remember, that winnability is now the new ideology of electoral politics. Shah is its pioneer and most successful living example.

For half a century, Delhi had not seen a truly powerful ruling party president. It is taking its time making adjustments. Shah has made other significant changes. The BJP’s parliamentary party meeting now takes place in the party office, and the Prime Minister comes there to attend. This changes the long-established practice of holding these meetings in the Prime Minister’s house for his convenience. The cabinet, chief ministers, even the heads of the most powerful government departments and agencies now acknowledge where power lies, besides the Prime Minister’s Office. They are shifting postures accordingly. This Karnataka verdict will make Shah’s domination even stronger, and affirm him further as a leader within his own right, if as a commissar more than a mass leader.