From Delhi to Davos, India’s ‘growth story’ has been described as a bright spot in an otherwise troubled global economy. While world economic output grew by 3.1 per cent in 2023, India’s economic growth rate, according to IMF estimates, is at 6.7 per cent. This is higher than that of any other major country or world region. India’s growth rate is so much higher than the average for emerging countries, that its exceptional status would even withstand some reduction, if the methodological concerns of critics are entertained.

India’s superior performance is projected by the IMF to continue in 2024 and 2025 (for whatever projections are worth). But should this outperformance be credited to India’s strength or to the world’s (and especially China’s) weakness?

In 2023, China was estimated to have had a real growth rate of 5.2 per cent, considerably above the emerging country average (4.1 per cent). China has maintained a growth rate of 9 to 10 per cent in every decade between 1980 and 2010 and almost 8 per cent in the decade until 2020. This was transformational growth, which, through the relentless mathematics of compounding, led China’s national income to grow around 30 times in real terms since 1980.

Even if China has not yet reached high-income status, the country’s ability to sustain an extraordinary growth rate over almost four decades has enabled it to rocket to a central position in the world economy, fundamentally transform the living conditions of its people, become a leading creditor nation, and catapult itself into the first league of geopolitical salience.

Why has China’s growth slowed recently? There is a fundamental economic reason, which has been compounded by policy failures.

Also Read: Whose economic performance was better, UPA or NDA? Growth rates don’t tell the whole story

Stagnation of Chinese economy

China has exhausted the fuel that underpinned its high growth over four decades. Several factors are responsible for this exhaustion: the end of China’s labour surplus due to industrialisation, urbanisation, and ageing; the exhaustion of its opportunities to use exports for growth; the accumulation of large investment and debt overhangs resulting from excessive reliance on investment over consumption, damaging profitability and instilling a warranted fear of bursting bubbles; and the failure to robustly shift into new technological and higher value-added areas.

The policy failures have been interrelated. First, China has failed to recognise the changed global environment. A growing unwillingness among China’s trading partners to bear sustained trade deficits as well as geopolitical tensions, especially with the United States, have diminished other countries’ willingness to rely on Beijing as a supplier and have decreased foreign investment into the country. Second, there was an exceedingly slow exit from Covid-19 lockdowns, which harmed business activity and confidence. Third, internal political repression has led to a crackdown on independently-minded officials and outspoken entrepreneurs, scaring foreign capital and causing domestic capital to avoid taking risks that could elicit government disapproval. Fourth, the government has failed to address the investment and debt overhang in any substantial way, even as crises have mounted, especially in the property sector. Fifth, it has failed to address the crisis through any significant stimulus. Due to these reasons, all linked to the missteps of the powerful Chinese state, the animal spirits of domestic and foreign investors have been severely affected, leading to decreased consumer demand, weak business investment, and the near collapse of China’s stock market.

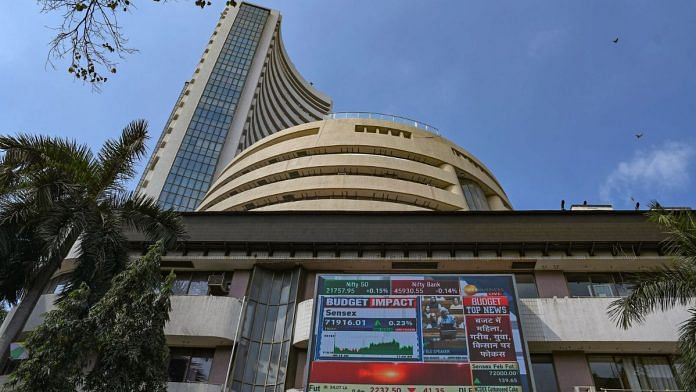

While China’s foreign direct investment inflows stagnated and then precipitously declined in the years since 2012, India’s have, in the same period, markedly increased, and are on track to exceed China’s this year. The growing international investor attention to India reflects the cumulative impact of its success in sustaining a growth rate of around 6 per cent since 1991. Despite major policy errors in the last decade—notably demonetisation—India’s performance has recently looked good in comparison to China’s.

Investors’ growing interest in India has surely reflected the comparative attractiveness of its longstanding institutional framework, for example, its legal system. In comparison, the greater arbitrariness of China’s legal, regulatory and political system creates not only uncertainties but also the possibility of serious policy errors that fail to be corrected for long periods. But this very realisation also suggests reasons for concern.

The sources of India’s attractiveness to foreign investors, and domestic business confidence, cannot be taken for granted. Although India’s youthful population positions it well, its people remain inadequately equipped to be brought into a modern labour force. Whereas the 1949 revolution raised the educational credentials of the entire Chinese population, the Indian labour force remains deeply under-educated. And this is one of the factors that has caused Indian growth to be limited to islands of prosperity.

There are other rate limiting factors too, such as poor infrastructure and weak domestic demand caused by the unequal pattern of development. But institutions are crucial. The confidence of business in India will depend in the long term not only on the rule of law—and therefore on the independence and effectiveness of courts—but also on that of regulatory and enforcement agencies. Unfortunately, it seems that this independence can no longer be taken for granted. And India’s top leadership, like China’s, seems increasingly prone to make decisions in a centralised manner that is neither consultative nor attentive to feedback. A further movement in the direction of capricious and autocratic control of the organs of state threatens to turn India into China without some of the latter’s advantages. Those who celebrate India’s ‘growth story‘ must be alert to this precipice.

The author is an economist at the New School for Social Research, New York. Follow him on X @sanjaygreddy. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

But I also think there is inherent hunger and aspiration in our young nation, which is so resilient that no one or two govt can so easily shake down.

Adanisation is the biggest threat. Non action (even of passive nature) of Sebi, RBI wrt Adani is seemingly visible. Adani being the default govt contractor with Modi being a personal deal broker is an open secret. India is reaping some benefits of Institutions and rule of law solely because of previous govts including Atal ji govt. Some good Ministers like Vaishnaw and Jaishankar is all we have got. Otherwise it’s all GundaRaj. Congress govt, barring Indira, was dynastic but not dyspotic, unlike Modi’s.

The only good thing is Modi is too old to become a lasting dictator. But there is genuine vaccum of good leaders anywhere else. RaGa looks Pappu to me, atleast politically.

India’s growth story is a sign of world’s weakness. The autocratic nature of BJP govt. which promotes a few business houses, leading to dangerous levels of inequality, presence of large number of uneducated people with a leaning towards mild religious fanaticism, etc. are not good for India’s economic growth.