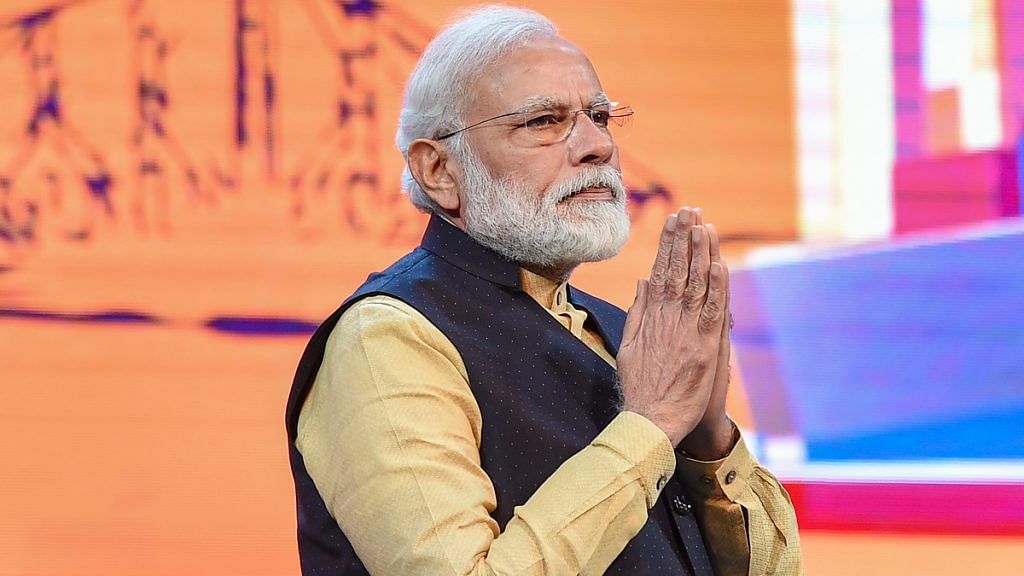

The wave of youth euphoria that Narendra Modi rode since 2014 appears to be ebbing. Six years into the Modi government, India’s youth appears disappointed and frustrated, according to the latest survey data accessed by us.

Without economic growth and jobs, how potent is Modi’s appeal to the youth? Will they be satisfied just with the politics of Hindutva and endless cultural wars?

Modi’s national appeal to the youth began in 2013 with his speech at Shri Ram College of Commerce, University of Delhi. He won them over with the promise of a new era of economic development that he said will fulfil their teeming aspirations. But now, there has been a breach in the wall.

Also read: Modi faces no political costs for suffering he causes. He’s just like Iran’s Ali Khamenei

Why is the youth disenchanted?

A majority of young people believe the economy is going in the wrong direction, according to Mint YouGov CPR survey. As many as 46 per cent of Gen Z and 44 per cent of millennials are worried about the direction of the economy, compared to just 31 per cent of Gen Z and 36 per cent of millennials, who are satisfied with the direction of the economy. This is in contrast to older people, who display net satisfaction with the economy, albeit very marginally.

Anecdotally too, quite a few educated youngsters who backed Modi earlier, now openly express their frustration at the mismanagement of the economy and the constant emphasis on polarising issues. It is then not surprising that the youngest cohort (18-25) in Delhi elections was the age segment most likely to vote for the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) over the nakedly communal politics of the BJP.

This youth disaffection with the prevailing state of the country has been building up for some time now. There are two reasons for this.

Also read: Modi got all the credit for lockdown. Now, he wants states to share risk of unlocking India

It’s the economy, stupid

First, the state of the economy. A government survey released last year suggested that 33 per cent of India’s skilled youth is jobless. This was also reflected in a March 2019 Lokniti poll that found unemployment to be the single-biggest political issue for voters. Then, Balakot happened, which swayed the youth back to the Bharatiya Janata Party’s camp.

The economic catastrophe brought on by Covid-19 and lockdown has further battered the youth, who are majorly employed in the less secure informal sector. As many as 27 million people between the age of 20 and 30 lost their jobs in the month of April alone, according to data from CMIE. Much of young India today is mired in uncertainty, having seen their colleges close, new opportunities vanish, and even existing ones in increasing peril.

Also read: The surveys can’t be true: Modi’s popularity has taken a beating with migrant crisis

And an ideology that divides

Second are the ideological issues that the BJP has focused on, particularly in the past one year, which have not found much resonance in the young. On questions related to the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), the National Register of Citizens (NRC), Article 370, and the protests at Jamia Millia Islamia University and Jawaharlal Nehru University, we find that the youngest cohort, the GenZ voters, are most likely to disagree with the Modi government’s stands, according to data from Mint Yougov CPR survey suggest. While both millennial and Gen Z voters narrowly backed the Modi government on most of these issues, the margin with which they did so was substantially less compared to older voters. In other words, the young are more evenly divided on these ideological issues than the old.

A majority of young voters also believe that Hindu-Muslim relations are going in the wrong direction. Gen Z supports this view even more strongly than the millennials, according to the survey data.

This relative ambiguity of Gen Z voters to hot button ideological issues could be influenced by the fact that a majority of those belonging to this group are either college goers or are about to finish secondary school. Most Gen Z voters (42 per cent to 33 per cent) disagreed with the police action at Jamia and JNU.

However, this trend must not be interpreted in terms of older conservatives and younger liberals, like in the West. For one, the evidence available on younger voters and their ideological moorings is ambiguous at best. While some surveys reveal, that on social issues, the young BJP voter is as liberal or conservative as a young non-BJP voter, there are others that suggest that young voters hold a jumble of liberal and conservative positions across various issues. Therefore, while previous surveys show that the Indian youth is becoming less conservative on social norms (marriage, dating, drinking), this is not likely to become an axis of political competition.

The current survey suggests that the younger voters show no distinct variation in self-identification with these terms across age groups. In fact, if anything, youngest respondents are least likely to readily identify with heavily politicised terms such as ‘liberal’, ‘secular’, or ‘feminist’.

Also read: Why the Modi government gets away with lies, and how the opposition could change that

But dissatisfaction doesn’t always convert into votes

These trends are merely an inkling of dissatisfaction, and do not imply that the Congress or any other opposition party can swoop in and reclaim their former vote share. Nor does this represent a serious political threat to Modi in an immediate sense. For dissatisfaction to translate into an electoral shift, voters need to see credible alternatives. There is no evidence that the young see the Congress yet as a credible alternative, including in the data accessed by us.

However, given that the BJP benefits immensely from the political majoritarian vote, the signs of an incipient age-based cleavage that appears to temper the party’s ethnic majoritarian-based cleavage seems to be a legitimate cause for concern.

Also, since much of Gen Z has come into adulthood in the Modi era, it has no strong memories of the 2011-14 period when Congress got delegitimised by a string of corruption scandals. This is a bloc that can potentially shift away from the BJP if targeted well. But unless the opposition parties actively and consciously try to address this disenchantment and aspirations of the young with careful messaging and an attractive alternative platform, they stand to gain little.

When the youth had got disaffected with the Congress at the fag end of UPA 2, a charming new suitor—Modi–pounced and swept them away. That suitor has now lost both his novelty and sheen, and the young appear disaffected again, but there are no new suitors on the stage.

Asim Ali and Ankita Barthwal are research associates at the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi. Views are personal.