Chief Justice of India N.V. Ramana recently remarked that appointments in higher judiciary should reflect social diversity and called upon the Chief Justices of high courts to ensure it while forwarding recommendations for appointment of judges. While the issue of imbalanced representation in terms of gender, caste, religion, etc. has often attracted attention, the issue of professional diversity in higher judiciary, which has become a monopoly of lawyer-judges, has escaped serious scrutiny.

A professionally homogenous judiciary can be hazardous for the ends of justice. A homogenous judiciary cannot cater to different perceptions and sensitivities, and creates a workforce with a lot of redundant skills. This type of judicial system will likely harbour latent prejudices, which may get ingrained in the judicial process. A clear example of this can be seen in the United States where the pre-eminence of lawyer-judges (judges who are appointed from the Bar instead of rising through a cadre-based service in the judiciary) has resulted in a pattern of biased decisions in favour of the lawyers’ community.

Benjamin Barton has ably demonstrated that the courts in the US have invariably favoured the interest of lawyers or that of the legal profession, often in an unfair manner, through dubious legal reasoning. For example, the case of Sahyers v Prugh, Holidays & Karainos, P.L. The US Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit created a legal obligation on the plaintiff’s lawyer to notify the defendant (a law firm) before instituting a suit under the Fair Labour Standard Act. This was in complete contradiction to the statutory requirement and this exception was created solely on the basis that the defendant was a law firm and the court held that such a notice would have helped the defendant avoid the lawsuit by exploring a settlement. This requirement was not created for any other category of defendants. Moreover, the plaintiff’s lawyer was denied his attorney’s fees for failing to serve a notice, which was not even necessary prior to this judgment.

Also read: India’s Supreme Court has a class bias and it takes whatever the govt says at face value

Collegium has amplified a historical legacy

Higher judiciary in India has always lacked adequate professional diversity. Out of the first 25 judges appointed to the Supreme Court of India, only three had any experience in subordinate judiciary. In the first four decades after Independence, of all the Chief Justices in the Supreme Court, only one was from the subordinate judiciary. As of today, there have been only two. However, after the inception of the collegium system in the 1990s, the professional homogeneity in higher judiciary has deepened further. The collegium has engineered a complete hegemony of lawyers. Earlier, even if not in the upper echelons of judicial leadership, judges from other professional backgrounds at least had a visible presence in the higher judiciary. Under the collegium, that presence has become effectively nominal.

Professional diversity in the Supreme Court

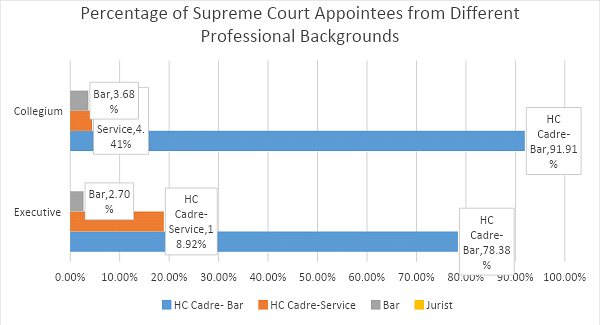

As per the constitutional framework, individuals from three professional backgrounds are eligible to be appointed as a Supreme Court Judge — judges of high courts (HC Cadre), practising advocates (Bar) and distinguished jurists. In reality, the majority of the judges in the Supreme Court are appointed from the HC cadre (96.76 per cent). Rest of the appointees (3.24 per cent) are appointed directly from the Bar. To date, no jurist has been appointed as a judge. A person is appointed as an HC judge from two backgrounds — judicial officers in the lower judiciary (HC Cadre-Service) and practising advocates (HC Cadre-Bar). Only 10.93 per cent of the judges in the Supreme Court have been from HC Cadre-Service.

However, these overall numbers flatter the collegium’s track record in this context. Before the inception of the collegium system, judges from HC Cadre-Service constituted 18.92 per cent of all the appointees. Under the collegium, the corresponding figure is 4.41 per cent. Also, pre-collegium, there were only three lawyers appointed directly to the Supreme Court without any prior experience of judgeship. The collegium has made five such appointments in less than 30 years.

Figure 1

Also read: Appointment of judges to higher courts governed by instrument lacking democratic scrutiny

Shortened tenure

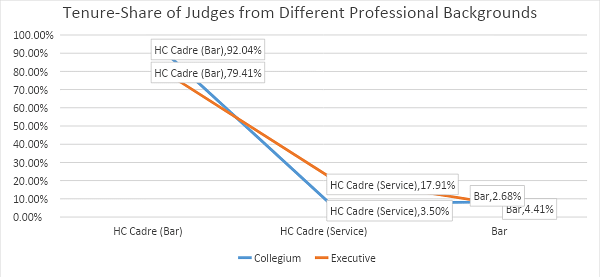

The extremity of this professional homogeneity is reflected not simply in the number of judges who are appointed from different professional backgrounds, but also in the tenure of such judges.

Under the executive, judges from HC Cadre-Service had an average tenure of 2,044 days and judges from HC Cadre-Bar 2,187 days. Under the collegium, it’s been 1,464 days and 1,849 days, respectively. Thus, while the tenure of judges from HC Cadre-Service was 6.54 per cent shorter than that of judges from HC Cadre-Bar under the executive, it is shorter by 20.82 per cent under the collegium.

Even this figure is heavily skewed due to the above-average tenure of Justice K.T. Thomas (2,132 days) and Justice R. Banumathi (2,167 days). The average tenure of other judges from the HC Cadre-Service appointed by the collegium is 1,121 days. To put this in perspective, 66 per cent of the judges from the HC Cadre-Service appointed by the collegium have a tenure that is around 40 per cent shorter than the average tenure of a collegium appointee.

On the other hand, only 4.8 per cent of the judges appointed by the collegium from the HC Cadre-Bar have such a short tenure. Under both the executive and the collegium, judges appointed directly from the Bar have inordinately longer tenure (2,141 days and 2,244 days) compared to judges from other professional backgrounds.

The extent of disparity in the tenure-share of the judges from different professional backgrounds is broadly similar to their proportion of appointments. Tenure-share is the share of judges from a specific professional background in the combined tenure of all appointees. However, judges from HC Cadre-Service have less than a proportionate tenure-share both under the executive (difference of 1.01 per cent) and collegium (difference of 0.91 per cent).

Figure 2

Also read: Under Bobde, pending cases rose in Supreme Court. Now they lie at the next CJI’s door

Professional diversity in the high courts

This lack of professional diversity in the Supreme Court can quite logically be traced to the skewed balance in the high courts. An analysis of the background of high court judges appointed between 1999 and 2015 shows that only 31 per cent of such judges were from the subordinate judiciary. This is in sync with the convention that judges from subordinate judiciary have an upper ceiling of one-third of the posts available in the high courts.

Additionally, while the median age of judges appointed from the Bar was 49 years, it was 56 years for judges appointed from Service. Such a policy blocks the prospects of judges from the Service cadre to assume any position of leadership. To illustrate, as on 1 June 2021, every single Chief Justice of a high court in India is from the Bar.

Homogeneity is rarely a good thing

It is overwhelmingly clear that lawyers have monopolised the higher judiciary not simply in relation to positions of power and influence but in terms of sheer presence as well. Currently, it is extremely rare for a judicial officer in the subordinate judiciary to be appointed as a judge in the Supreme Court or even become the Chief Justice of any high court. As mentioned earlier, existing research indicates that professional homogeneity on the bench is very likely to lead to biased and prejudiced decision-making and compromise the integrity of the judicial process. Even discounting its effects on the quality and pattern of judicial decisions, in a fundamentally pluralistic society like India, homogeneity of any kind is an undesirable aspect.

Rangin Pallav Tripathy is faculty at the National Law University, Odisha, and has recently completed his Fulbright Post-Doctoral Fellowship from Harvard Law School. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)