While New Delhi sees the sense of promoting regional connectivity, it has serious strategic concerns about working with China on its eastern border.

Beijing’s growing collaboration with India’s neighbours has created a sense of unease in New Delhi.

China’s emergence as a regional strategic and economic actor has reshaped the prospects for connectivity in Asia. Beijing has demonstrated a newfound sense of political will to undertake regional connectivity initiatives, supported by the country’s surplus capital, a shift that has changed the security environment in India’s neighbourhood.

Naturally, as China’s influence in South Asia grows, India is faced with the challenge of managing its relationship with its biggest neighbour and competing to maintain its prominence in the region.

India has begun to view China’s commercial initiatives as a means to advance its strategic ambitions in ways that often are not conducive to India’s interests. The view that connectivity offers a set of tools to influence other countries’ foreign policy choices has become commonplace in analysis about the China-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The BRI has garnered much attention, positive and negative, since its inception in 2013. It is one of the world’s biggest initiatives for promoting connectivity and providing funds to finance infrastructure development. In South Asia, the BRI underscores the growing Sino-Indian competition in the subcontinent and the Indian Ocean region.

Also read: Modi govt beats China in high-stakes battle over dam in Nepal

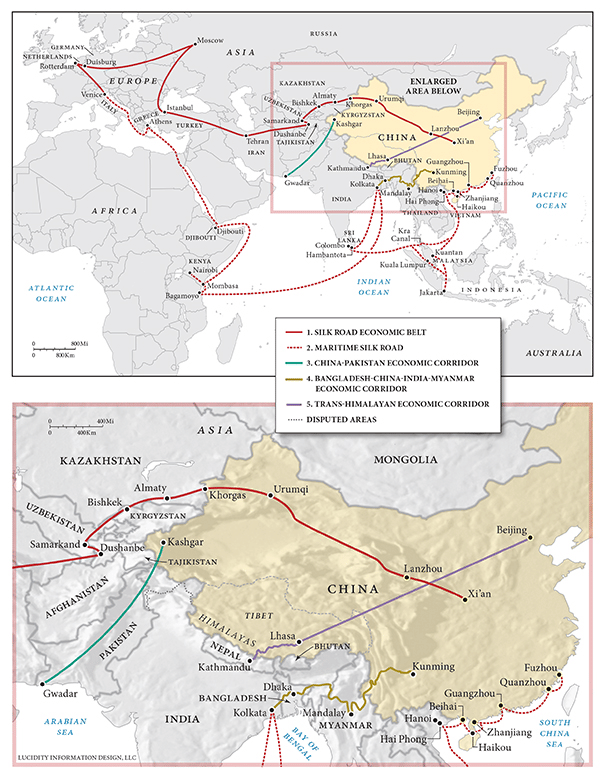

India has started to craft a policy response. In its strongest stance on the BRI to date, India marked its protest by not attending the Belt and Road Forum that China hosted in May 2017. In official statements, India questioned the initiative’s transparency and processes, and New Delhi opposed the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) due to concerns about territorial sovereignty. As India calibrates its policy response, instead of perceiving the BRI as one project, it would be wise to look at the initiative as a culmination of various bilateral initiatives, many of them involving projects that were actually initiated before the BRI itself was formally launched. The Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM) Economic Corridor, for instance, was launched in the early 1990s. Similarly, China’s Twenty-First Century Maritime Silk Road (MSR) is a combination of bilateral infrastructure projects in the Indian Ocean region that China has sought to present as a multilateral initiative.

To best understand India’s concerns, it is helpful to examine four specific corridors that constitute major components of the BRI and run through India’s South Asian neighbourhood: the CPEC, the BCIM Economic Corridor, the Trans-Himalayan Economic Corridor, and the MSR.

These four corridors and the infrastructure projects associated with them have a direct bearing on India’s strategic interests. They run close to India’s continental and maritime borders and are affecting its security interests and strategic environment. China’s engagement with India’s immediate neighbours through these corridors threatens to alter existing power dynamics in the region. India is not opposed to infrastructure development in the region, but it is concerned about the strategic implications of certain Chinese-led initiatives. A primary concern for New Delhi is that Beijing will use its economic presence in the region to advance its strategic interests. One notable example is the strategically located port of Hambantota, which the Sri Lankan government was forced to lease to China for ninety-nine years in 2017. The port was built using Chinese loans but, due to the high interest rates, Sri Lanka was unable to repay and incurred a burgeoning debt burden.

India will have to work with its partners in the region to offer alternative connectivity arrangements to its neighbours. To date, New Delhi has been slow in identifying, initiating, and implementing a coherent approach to connectivity in the region.

The way forward

Connectivity is increasingly seen as a tool for exerting foreign policy influence.

Given the geopolitical stakes and India’s reservations about how China’s BRI connectivity projects are currently being pursued and the strategic advantages they may confer, there is likely little scope for the two countries to collaborate on the BRI.

India perceives efforts to enhance interconnectedness as a new theatre for geopolitical competition with China in South Asia and the Indian Ocean. At the same time, connectivity also presents India with an opportunity to reestablish its regional primacy.

On initiatives like the BCIM Economic Corridor that include both China and India, New Delhi probably will continue to drag its feet and slow down discussions. There may be limited opportunities for collaboration through institutions that count both India and China as members, but the increasing mistrust in the relationship will hamper any positive momentum. When it comes to outstanding invitations to participate in other Chinese-led initiatives like the MSR, New Delhi will remain hesitant, knowing that joining such projects is not in its strategic interests. will likely maintain bilateral collaboration with countries like Japan while also remaining engaged with entities like BIMSTEC and the Bay of Bengal community, of which China is not a part. Most of all, India must stop underestimating Chinese goals and ambitions in the region.

Ultimately, India must be more proactive. While China is successfully implementing development projects hundreds of miles from its borders, India is still struggling to craft domestic development plans for its own border regions. New Delhi intends to prioritise development in its international engagement, but India will have to weave together its ad-hoc initiatives into one coherent road map to regional connectivity and infrastructure construction. Even as India must address infrastructure and development needs at home, it also needs to provide an alternative to China’s overtures to the region. To this end, India must not only respond to the changes Chinese engagement is prompting in its neighbourhood but also collaborate with partners to further its vision of regional connectivity, while accounting for its own capacity and resource limitations.

Also read: Malaysia doesn’t have the appetite for China’s One Belt One Road initiative anymore

Until the advent of the BRI, New Delhi did not feel its bilateral relationships with its neighbours were threatened as there was no such competition between India and leading donors in South Asia, like Japan. China’s rise not only introduces a new actor in South Asian dynamics but also highlights the underlying fact that Beijing’s influence in the region comes at a cost to India’s role and profile as a regional leader. China’s engagements in South Asia are a result of its global ambitions to be a great power.

India currently lacks the resources to compete with China in terms of global power ambitions, and this shift undoubtedly affects New Delhi’s strategic and national interests.

In some cases, India can take steps on its own to sharpen its response. To begin with, India will have to clearly account for its resources and capabilities related to connectivity and infrastructure development. The current government understands the urgency of acting boldly to address the changes in its neighbourhood, efforts that will require fresh thinking and new approaches, such as the concept of burden sharing. New Delhi must invest in and develop its strategic assets—like the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, for instance—to project power across the Indian Ocean.

These unilateral steps notwithstanding, India’s ongoing response might not be enough to provide neighbours with a feasible alternative to Beijing’s continental and maritime projects, in light of New Delhi’s significant resource limitations. Given India’s massive mandate to develop much-needed infrastructure domestically, the country’s ability to act alone in South Asia and the larger Indian Ocean is further limited. New Delhi cannot and need not act alone.

Fortuitously, convergence between the strategic interests of India and other regional actors (especially Japan) have provided both incentives and opportunities for collaboration.

New Delhi must seek help from partners like Japan when necessary to build and upgrade its infrastructure and create an alternative to Chinese-led connectivity corridors and infrastructure projects. India must have a blueprint to identify specific projects, mechanisms, and goals for its connectivity initiatives. Other countries like Australia, France, Germany, the UK, and the United States are keen to see India play a leading role in the region. These nations have technical expertise and are already present in the region to some degree. New Delhi must identify the advantages each of these states offer and leverage them to collaborate in areas of common interest and pursue its strategic connectivity goals.

While India seems to have identified partnerships as a way to address its connectivity challenges, it must now be deliberate about the nature and scope of relevant projects in the region. So far, New Delhi’s response has been reactive and inadequate. If India continues to pursue a reactive policy, it will exhaust its limited resources chasing China as Beijing strives to become a regional and global power.

As the BRI and other connectivity projects transcend and reimagine boundaries and connect Asia with far-flung locations around the world, policymakers have to grapple with new ideas and challenges. Competition and other diplomatic interactions between China and India bilaterally, in their neighbourhood, and on a global scale will shape Asia’s new security architecture and determine the region’s economic and strategic terrain for many years to come.

This article is an edited extract of the article titled “India’s Answer to the Belt and Road: A Road Map for South Asia” that appeared on the Carnegie India website.

It has been republished here with permission. You can read the full article here.

Some of the Chinese apologists in the commentariat (Jha, Bhadrakumar et al) seem to be advocating the position that India “fall in line” and queue up for this.

However, if anyone has ANY doubts, he should read the book “The New Confessions of an Economic Hit Man” by John Perkins. The similarities are uncanny, only that it’s the Chinese Empire this time around, and maybe, unlike the US, hit men have so far not been employed to assassinate leaders and those asking inconvenient questions (who knows, however) . But make no mistake: This Belt and Road initiative is nothing but an exercise in advancing the interests of the Chinese military industrial complex. Any benefits that emerge may be incidental and unintentional. It’s much more likely that the weaker countries that fall for this stratagem will find themselves in a debt trap, ravaged environment and economic enslavement of millions.

India should be strong and do exactly what is required for its own interests. Which is, the greatest good of the greatest number.

Very good article. India should not compete with China because they have much ahead of India. They have global leadership role rather than engaging in neibouring countries.

India had first mover advantage for development of hydel power in Nepal, even more so in Bhutan. Could not deliver. Bhutan faces its own version of a debt trap. More than competing with someone else, it makes more sense to develop our economic potential more fully. As for China, its ( including Hong Kong ) annual foreign trade is close to $ 5 trillion. The connectivity projects it is undertaking are organically linked to its being the world’s largest trading nation. Legitimate concerns have been raised about the economic viability of some BRI projects, the cost of finance, exclusivity for Chinese firms in getting construction contracts. It would be in the interests of both China and its partners to ensure that all of this remains in the win win zone.