If the Indian economy was a car, its last stable wheel is now starting to wobble. The private investment wheel has been wobbly for a while now, contributing less and less to the economy’s forward momentum. The export and import wheels have both slowed significantly, thanks to the global economy. Now, the final wheel—household consumption—is starting to show distressing signs of impending failure.

What this means is that the engine propelling the economy forward—government spending—is at a growing risk of overheating. Not only will the government have to continue shouldering the investment burden, but it will also have to increase its subsidy spending.

Steps towards this have already started. The central government and various state governments have already announced freebies to help people reduce their spending. The problem is, these are populist politicians’ fixes to a problem that needs expert policymakers.

While governments and parties view the issue through the political lens of gaining votes, they are missing the policy imperative of averting an economic crisis. Incidentally, this kind of crisis of poor private investment and low consumer spending will bring us full circle to what kicked off the Indian government’s socialist push in the 1950s.

Also read: Why Indians are racking up huge credit card bills — stagnant or shrinking incomes, higher spending

Spike in spendings

The emerging problem with household consumption has to do with how it is being financed, which reveals a lot about what’s happening with India’s consumers. Credit card debt is increasing sharply, largely because people seem to be spending well beyond their means.

Reserve Bank of India (RBI) data shows that outstanding credit card dues rose to Rs 2.13 lakh crore as of July 2023, 31.2 per cent higher than July last year. This in itself wouldn’t be a problem. Spending money on your credit card is not a bad thing, and a lot of people do it for credit points and rewards.

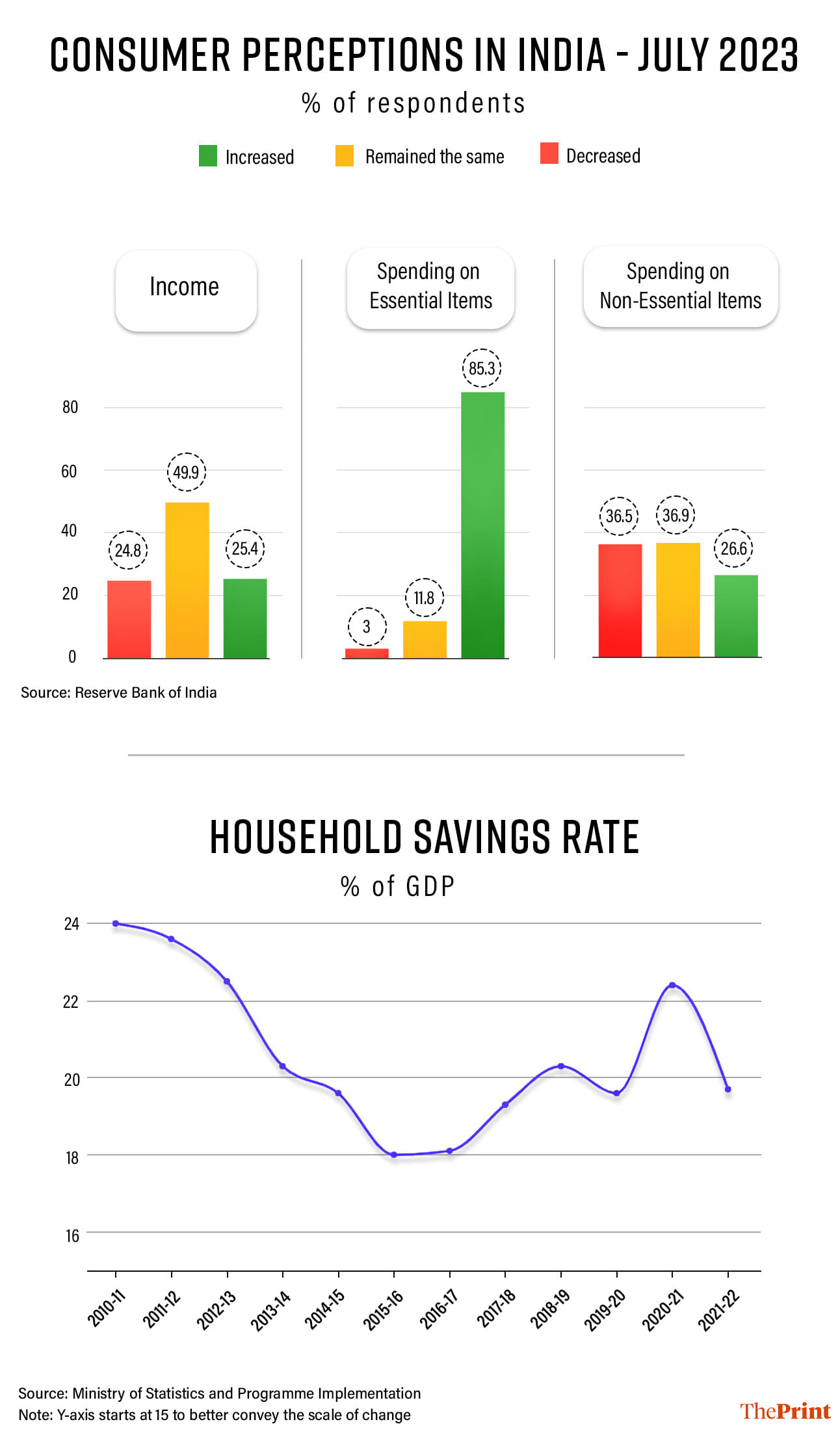

However, if you combine this increase in credit card spending with another dataset from the RBI, the scope of the problem emerges. The central bank’s Consumer Confidence Survey for July 2023 shows that 85 per cent of the respondents said their spending on essential items has grown over the last year.

Now, one can argue that prices tend to increase over time. Indeed, they should rise in a growing economy—growth and inflation go hand-in-hand. But, when it comes to a survey, people report changes only if they are out of the ordinary. So, if 85 per cent of the people are saying their spending on essentials has increased, it’s because the spike has been significant enough to pinch.

Another 12 per cent of the respondents said their spending on essentials remained the same as last year. Since inflation has been at a pretty brisk pace over the last year, it’s likely these people have been buying lower quantities of essentials—a sure sign of economic distress.

On non-essentials, a little more than a quarter of the respondents said their spending had increased, while about 37 per cent said it had remained the same.

To put it simply, most people saw their essential spending increase, many saw their non-essential spending increase, and yet others saw the latter remain the same.

Now, contrast this with the fact that only a quarter of the respondents said their incomes rose over the last year—about 50 per cent reported no change and a quarter said their incomes actually decreased.

So, you have most people spending more, especially on essentials, but earning either the same or less. No wonder they are increasingly turning to credit cards and ‘Buy Now, Pay Later’ schemes.

Also read: Stable economy, unstable deals—How Modi govt’s well-intended sudden bans hurt India globally

Doles for policy crisis

If results of the RBI survey aren’t convincing enough, then perhaps the household savings rate might help. After all, if households are doing well, they would be saving more money, right? The household savings rate, however, has been pretty low—except for a lockdown-induced surge in 2020-21—and the broad trend over the last decade has been of decline.

Still not convinced? How about expenditure on items that people don’t usually use credit cards for, such as cars and two-wheelers? If households are doing okay, then sales for these items should be robust. But that’s not the case.

After two years of contraction in 2020-21 and 2021-22, two-wheeler sales finally shot up by about 17 per cent in 2022-23. But this has dramatically slowed down once again, with Care Ratings saying 2023-24 will end with just 6-8 per cent growth in this category. Passenger vehicles have done better, but all evidence points to the fact that sales are being driven by premium variants and SUVs—decidedly not the vehicle of choice for the aam aadmi.

Governments and political parties understand the problem at hand—the consumer is barely hanging on. But the problem is they are viewing it as a political issue rather than a policy one.

So, you have LPG subsidies from the Centre being given to all families and not just the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana ones as was the case earlier. Free food schemes continue long after they should have ended. The Congress is making good on its pre-election promises in Karnataka, all of which are doles of one kind or the other. Sonia Gandhi has promised more of the same in Telangana.

Unfortunately, what’s missing is an acknowledgement of the problem—at the Centre or even state levels—and a plan to solve it. This is what happens when politics so comprehensively overshadows policy.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)