Vichardhara kya hai tumhari…(What is your ideology?)’ I had asked to a group of 18-year-old boys that I met at Jaunpur during my recent election travel. They replied, ‘woh kaun dekhta hai…hum toh vote Modi-Yogi ko denge’. It’s not like they didn’t know what the word ‘ideology’ meant, they did muddle about Hindutva and Hindu Rashtra; it’s just that they don’t need to apply any ideology to shape their political musings. Rather for them, their attachment to politics is moulded by their personal instincts and liking to the leader, Modi ji, and their way of politicking.

Something similar had happened at a family function in my mother’s village in Rajasthan. Election talks of Uttar Pradesh and Punjab had stirred the conversation to Rajasthan assembly elections of 2023. Politics of Rajasthan has always been dominated by either the Congress or the BJP. So, it was a little shocking when some of the cousins mentioned AAP as their preference. When I inquired why, they had no definite answer. One said ‘bahut ho gaya Vasundhra aur Gehlot, Rajasthan needs change’ while for the other, it was the pull of Arvind Kejriwal and his ‘clean image’.

‘Par haan desh ke liye, hamesha Modi ji’, I was reminded as a matter of fact, by my cousins, in case I took them as ‘anti-Modi’ supporters.

Also read: Delhi can finally breathe clean air in winter—if Punjab’s new AAP govt can convince farmers

Instant politics and populism

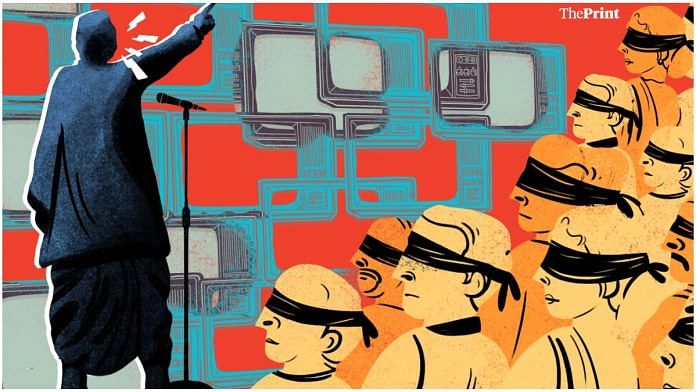

The public discourse has become devoid of the nuances that once used to fascinate and grip the ideological narrative. The public of today, particularly the young and the restless, have lost patience and their desire is for instant politics, like instant noodles. As such the political behavior of the voter has undergone a change. Gone are the days when over cups of tea and charcha, election manifestos would be discussed. Gone are the days when loyalty to a party would be based on ideology, policies and performance. In the time of WhatsApp and social media, nobody wants to read those boring manifestos with big ideas anymore. Their demand is for instant benefits, for freebies. They want snappy videos of castigation, of politicians of other parties being presented in poor demeaning light.

People want a nayak to relate to, a mahanayak who adds zing to the narrative, and a khalnayak for entertainment and sneering.

Have India’s traditional ideological clashes faded out in these newer times? Have we entered the ‘post-ideological times’? Or is the new -ism of New India — ‘populism’?

Populism has barely ever been considered or used as an alternative to ideology to understand the phenomena of Narendra Modi and his politics. When Aatish Taseer wrote an article in the Time Magazine in 2019 — “Of the great democracies to fall to populism, India was the first”— he had faced the wrath of the Modi Sarkar.

In 2004, a young Dutch political scientist named Cas Mudde published The Populist Zeitgeist, a paper that proposed a new and concise definition of populism. He defines populism first as the idea where society is separated into two groups, at odds with one another — “the pure people”, understood to be fundamentally good and “the corrupt elite”, understood to be fundamentally corrupt and out of touch with everyday life. As per the second definition, populists believe that politics should be an expression of the “general will” – a set of desires presumed to be shared as common sense by all “ordinary people”.

If we apply this theory to understand the newer political discourse that has been shaping India, a picture emerges.

In 2014, Narendra Modi made the Prime Ministerial appeal as a humble candidate with no strings attached, having an ordinary background with roots in a poor family. Proclaiming himself as chaiwala, kaamdaar, and a chowkidaar (in 2019), Modi tapped into the sentiments of the people. He launched attacks on the Congress, saying they are a party of naamdaars who were born with a silver spoon in their mouth. Dynastic politics thus became a depraved term. So high was the rhetoric that a narrative was set which was emotional in its political tone and exciting in the rhetoric, thereby giving Modi his first thumping win in 2014. A narrative that has been repeatedly put to use in multiple assembly elections since then. And five years later, in 2019, it became only larger, encompassing the expression of the ‘general will’.

Today, the mood is at its zenith, incessantly being cultivated, of Hindus being persecuted in their own land, and becoming more righteous post The Kashmir Files. Narendra Modi (along with Yogi Adityanath) has imbued into the conscience of the people that if there is anybody who can keep India safe from invaders (Pakistan) it is them. Adding to it the belief of the parent organisation of making India a Hindu Rashtra, Narendra Modi has invincibly become the common sense of the people.

Also read: BJP is no longer just a Brahmin-Bania-Zamindar party. UP’s ‘labarthis’ show why

AAP and the post-ideological times

But it’s not just Modi, Arvind Kejriwal too is fast becoming a formidable contender in national politics. Today, Kejriwal has a following in Rajasthan where his party has no visibility, where the local journalists claim that it will take another election (maybe by 2028) to establish ground in the mind and heart of Rajasthan. But the mood is already brewing for him.

Kejriwal’s AAP is a classic political example of the post-ideological times. A party which is devoid of ideology or political leanings, minus any caste, creed or identity politics, yet has managed to fill the vacuum of the other alternative. To establish himself in politics, Kejriwal clung to the ideas and ideals of Mahatma Gandhi, donning the topi of aam aadmi. But when the mood changed, Gandhi was replaced by Bhagat Singh and with topi came the recitation of Hanuman Chalisa. Swaying with the time, Kejriwal filled the dots of not becoming an -ism of any traditional ideology artfully. He offers ‘free electricity and employment’ to counter Modi’s ‘free ration’, he takes upon corruption to counter Modi’s ‘parivarvaad’ attack and to counter the ‘Gujarat Model’, Kejriwal has developed a ‘Delhi Model’ thus sweeping the state of Punjab.

AAP, akin to BJP of Modi, has become a political party of newer times, built for a crowd that jiggles and thrives on boisterous cult personalities.

Along with job, money, security, janta also craves for flamboyance and sloganeering like Bulldozer Baba, Modi hai to mumkin hai, double-engine sarkar. It is about Yogi ‘bulldozer’ baba vs Akhilesh ‘bhaiya’ Yadav, Narendra ‘hope’ Modi vs Rahul ‘Pappu’ Gandhi.

Narendra Modi and Arvind Kejriwal, both, in some ways have become the icons in this post-ideological populism movement, one that consistently promises to channel the unified will of the people, and by doing so undercuts the self-serving schemes of the elite establishment. Maude, however, clears to say that populism is not a fully formed political ideology like socialism or liberalism rather it is a “thin” ideology.

The sheer defeat of Congress and the smaller regional parties in the recently concluded assembly elections have made them irrelevant to the politics of newer times. Congress leader Shashi Tharoor wrote in a national magazine, claiming ‘Congress is essential for India and how it can be revived’. He explains the ideology of the party, reminding of the past, secularism, and the economic prosperity India achieved under the party. But he forgets that the newer generation does not care. For them, the traditional ideologies have been sidelined with a simplistic narrative of ‘Left is bad, Right is good’, one that has become the pragmatic reasoning.

In New India, the concept of development, a commitment towards nation building upon ideology, is not finding space in the ‘instant’ mood and political behavior of the new generation. Narendra Modi and Arvind Kejriwal, followed by Mamata Banerjee, KCR, Jagan Reddy, all are speaking a language directed to an audience that wants no attachment to inclinations or beliefs.

Populism is here to stay, cementing robustly and perhaps becoming the ‘ideology’ of New India.

Shruti Vyas is a journalist based in New Delhi. She writes on politics, international relations and current affairs. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)