As the analyses of the recent Lok Sabha elections slow down, we should ask how India embraced a liberal model of representation at its founding.

How did we arrive at an understanding that the many identities that one shared in one’s social life did not have to be interpreted and fixed, and then mapped onto one’s political identity?

The remarkable feature of India’s founding moment was the arrival at this understanding. It formed the core basis of India’s Constitution, and of the kind of liberal individualism that Jawaharlal Nehru sought to further. Nehru’s worry with communal identities, sharply revealed for example in his fortnightly letters to India’s chief ministers, rested precisely on how no fair solution to the problem of identity could be found within the paradigm of group identity politics.

One of the notable features of India’s Constitution is that it put in place a schema of representation that was, for the most part, centered around individual freedom. It focused on the freedom of the individual from the tyranny of group identities.

Also read: Remembering Nehru, the ‘favourite target of disinformation’ in Indian politics now

Why was this so? Why, for example, did the constitutional framework not recognise caste groups in a more thorough-going fashion? How did Nehru and others manage to resist attempts to award Muslims special treatment as well as succeed in creating a model that would treat Muslims as equal citizens in the aftermath of extreme religious polarisation and violence?

In answering such questions, one has often focused on the ideological orientations of India’s founding figures. But the ideology of the time emerged out of a specific historical context, namely civil war and the Partition of British India. The several decades before the Partition experienced complex power-sharing mechanisms between different groups in India. For a period of four decades prior to the division of territory, India’s constitutional politics was an attempt to arrive at some kind of arrangement between different groups through policies as diverse as weightage (granting groups representation greater than a proportion of their population); reservations (the use of fixed quotas); and separate electorates (the bifurcation of the electoral map).

The Partition of British India in 1947 marked a complete breakdown in such kinds of arrangements. The moment captured the instability and eventual unsustainability of a group-sharing paradigm. A number of India’s major founding figures did have normative reasons for opposing such a paradigm – it was at odds with self-rule because it treated citizens as part of a compulsory group rather than as individual agents. But this understanding came into being because of the harsh reality of Partition. The division of territory revealed that any power-sharing mechanism that constructed a polity around the majority-minority framework was bound to fail.

Also read: Three things Indian liberals held dear were tested this Lok Sabha election

In the decades prior to India’s independence, there was an astonishing crisis of representation. Across the political spectrum, there were few efforts to conceive of citizenship as something that was unmediated by communal identities. There was either an attempt to construct a vision of Indian politics where one’s identity was tethered to an existing community rather than to oneself as an individual – the vision, for example, held by the Muslim League and the Hindu nationalists. Or, there was a kind of denial of the problem posed by representation in India, a denial that leaders of the Indian National Congress were sometimes accused of when they saw the communal problem as being merely a cover for underlying economic tensions.

With Partition, the reality of the problem posed by representation in a diverse society could not be denied, and the failure of existing frameworks was highlighted. Any framework that saw India as a constellation of groups would ultimately provide no solution at all. Majority groups would draw strength from numbers and from a procedural and thin understanding of the democratic principle. Minority groups would question why might in numbers should determine rights and would seek a model that diluted the significance of their numerical reality.

What Partition captured was how, under this dynamic of fixed group identities, there was no lasting solution to the problem of representation. Different groups would rise and fall in time, but every single group would suffer some sense of injustice no matter how the pie was sliced. The only solution lay in a model of citizenship that could be decentered from identity. A model would have to be constructed where every person was a free individual, acting as agent, and could be part of a democratic polity where one’s political identity was constantly fluid and changing.

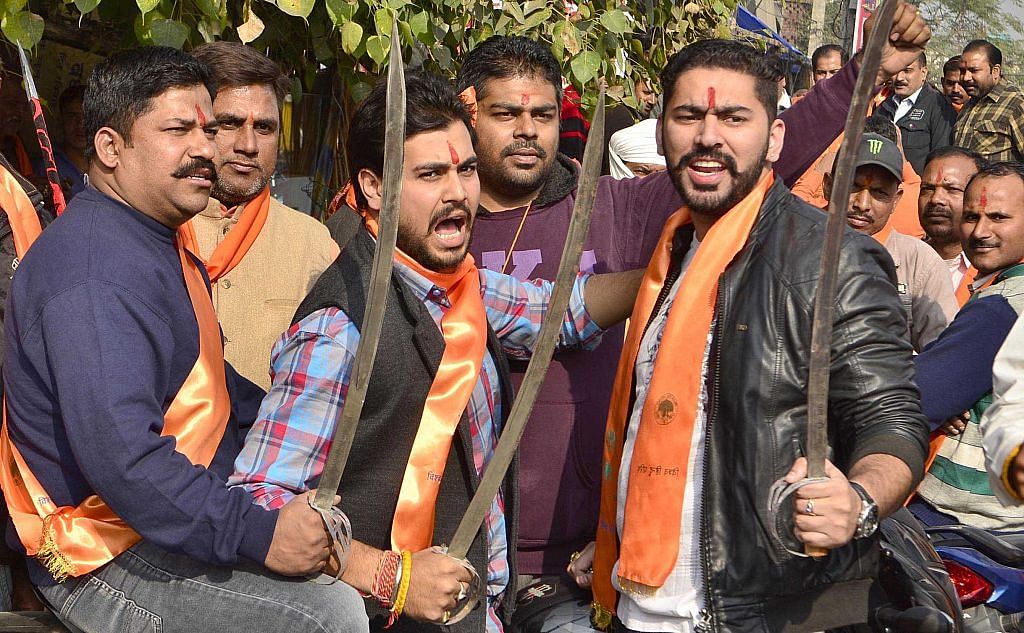

The tragedy of Indian politics for some decades now has been a complete rejection of the nation’s founding insight. Whether one sees the truth of India’s reservation scheme, which has displaced the goal of annihilating caste and instead created a system where power is shared between different caste groups, or confronts the Hindu-Muslim question, where leading parties have often either focused on Hindu nationalism or run Hindu nationalism and Muslim nationalism alongside one another. There have been few attempts to construct a politics on an entirely different basis. (Prior to its implosion, this is partly what made the AAP such an interesting experiment.)

Also read: What Sardar Patel said on Ayodhya is relevant to mediation today

Many expressions of fear about our current politics are correct but, if the lessons of Indian history hold, the solution to moving beyond Hindu nationalism will lie in moving beyond identity.

Madhav Khosla, co-editor of the Oxford Handbook of the Indian Constitution, is a junior fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows. His book, India’s Founding Moment: The Constitution of a Most Surprising Democracy, is forthcoming from Harvard University Press. He tweets @MadKhosla. Views are personal.