On 16 July 2020, my article predicted the recent tactical agreement on disengagement, as well as the yet-to-be-negotiated de-escalation and de-induction almost to a T.

I wrote: “The compromise acceptable to both the countries appears to be to revert to status quo ante April 2020 with ‘buffer zones’. China gets the 1959 Claim Line and we get status quo ante April 2020 albeit with ‘buffer zones’. Both sides save face.”

The contours of the four agreements reached between July 2020 and September 2022, as well as the 21 October disengagement agreement, follow this predictable pattern. The exception is that in the Depsang Plains and Charding La, coordinated patrolling can be carried out; however, like in all other buffer zones, no deployment or infrastructure development can take place.

I have no doubt that the Special Representatives, diplomats, and military commanders will take the agreement forward to achieve de-escalation/de-induction, probably culminating in a broader agreement to manage the entire border. Already, though, one fallout of the crisis has been the de facto delineation of the 1959 Claim Line—the Chinese version of the Line of Actual Control (LAC)—at least in the most contentious areas of the dispute.

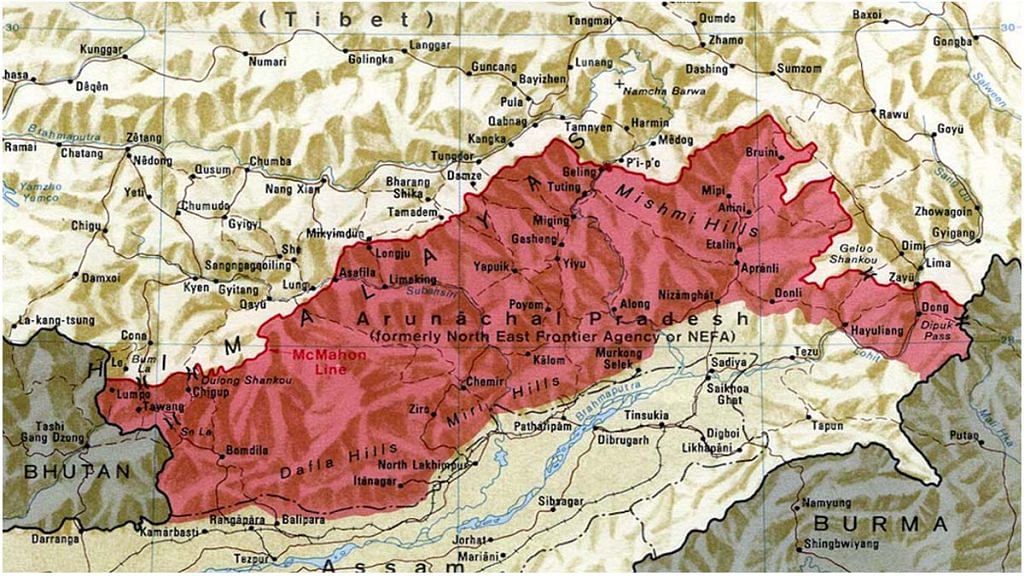

The moot question, then, is why this delineation cannot be extended to the rest of the LAC and the McMahon Line, where the thickness of the pen on a small-scale map creates areas of “differing perceptions”. I dwell on the hypothesis that the India-China border cannot be substantially changed and should be formalised along the 1959 Claim Line and the McMahon Line in the Eastern Sector through an interim strategic agreement, if not a final settlement of the boundary dispute.

Also Read: India-China disengagement is tactical. Won’t impact border dispute or power tussle

India–China border cannot be changed

Ever since the treaty of Westphalia, territory has been central to the idea of a state. In civilisational states, this idea is even more ideologically entrenched, leading to disputes caused by emotional links to the historical spheres of influence. This was the root cause of the clash of civilisations in the overlapping spheres of influence in the Himalayan frontier, apart from the hegemonistic competitive conflict among nations.

The consolidation of the Himalayan frontier region by both sides led to the 1962 War. Since then, the borders have not substantially changed despite a violent skirmish at Nathu La in 1967 and a series of confrontations along the LAC at Sumdorong Chu in 1986-87, Depsang in 2013, Chumar in 2014, Doklam in 2017, and during the crisis in Eastern Ladakh since 2020, which included a gory fight without firearms in Galwan.

Nations armed with nuclear weapons and maintaining large professional armies do not—and, I dare say, cannot—fight decisive wars that result in major loss of territory. Even the probability of a limited war is very low. Despite civilisational claims, ideological drum-beating, and nationalistic emotions over “lost territories”, little has changed along our western and northern borders—and little is likely to change in the future. The crisis in Eastern Ladakh proves this point.

Indeed, below the nuclear threshold, China has time and again exploited the border dispute to trigger crises to impose its hegemony and shape India’s conduct in the international arena. Its initial success in Eastern Ladakh in 2020 was primarily due to India being strategically and tactically surprised at both the political and military levels. Also, India committed the cardinal sin of aggressively developing border infrastructure in sensitive areas without deploying troops or establishing ITBP posts in un-held areas along the LAC. Despite numerous medieval-style “fist and club” confrontations since Nathu La in 1967, no Indian post has ever been physically attacked and overrun by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

The recent events have brought lessons for both sides. For China, the most important lesson from the Eastern Ladakh crisis is that using border disputes to assert hegemony offers diminishing returns. And for India, it is that it must physically man the border to prevent being caught off guard.

The above analysis raises two fundamental issues. First, how best can India prevent embarrassment on the border from a militarily superior and untrustworthy China? Second, if both sides have learned their lessons, what might be the contours of an interim strategic agreement to maintain peace and tranquillity along the borders?

Strategy of denial

India needs to implement an aggressive operational strategy of denial to manage the border. This strategy is based on the assumption that China is untrustworthy and will continue to trigger incidents on/across the LAC to assert its hegemony. The cost of manning the northern front and the rigours of the environmental factors are often overplayed by the media and the public. If a large standing army cannot defend the borders, then what is it being maintained for?

After the de facto delineation of the LAC/1959 Claim Line under various agreements since April-May 2020, India should unilaterally and formally make a public declaration of the alignment of the LAC. This would establish the LAC as the redline, a violation of which would be considered an act of war. Marked maps should be handed over to the PLA during border meetings. The LAC should be continuously manned by the ITBP, with posts established as close to the line as terrain permits. According to media reports, a total of 195 ITBP posts are deployed along the 3,488 km-long northern border. In my view, this number should be tripled.

The quantum of troops deployed for defence, and their reaction time, must match the PLA’s offensive capability. Defensive formations should be located within striking distance of their permanent defences, with adequate infrastructure created, if not already done.

In Ladakh, to cover the long distances between the LAC and the main defences due to terrain configuration, a strong mechanised covering force should be deployed. The same force can be utilised to preempt or prevent any incursions by the PLA. Further, defensive formations must have a tactical offensive capability for an immediate quid pro quo. Mobilisation of strategic and operational reserves with a focus on offensive operations must be streamlined. A similar pattern must be followed in the northeast, adjusted for terrain variations.

Finally, fail-safe surveillance and reconnaissance with satellites, drones and electronic devices must be ensured at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels to prevent being surprised.

Also Read: Indian Army’s first brush with the PLA was in 1951. The windfall was Chushul airfield

Contours of an interim strategic agreement

The concept of the LAC was first proposed by Zhou Enlai in his famous letter of 7 November 1959. In Eastern Ladakh, the PLA considers the areas it secured up to that point as the LAC, also known as the 1959 Claim Line, with coordinates outlined during the India-China Official’s Negotiations in 1960. India never recognised the 1959 Claim Line, but the term ‘LAC’ began to be informally used since then. After the 1962 war, when the PLA unilaterally withdrew 20 km from this line, India gradually secured some areas across it. Thus, the areas of differing perceptions emerged due to the rival versions of the LAC.

In the northeast, the McMahon Line—that emerged out of the tripartite Simla Convention of 1914, which China disowns—serves as the de facto border. Since 1959, China has refused to recognise the McMahon Line, and since 1985, it has claimed the entirety of the North-East Frontier Agency (now Arunachal Pradesh). Thus, this line also came to be loosely referred to as the LAC. The differing perceptions of the McMahon Line stem from the ‘thick pen’ used to mark it on a small-scale map at Simla, and from variations in interpreting the watershed principle to define mountainous borders. This ambiguity is the cause of confrontations in the northeast.

During the 1993 Border Peace and Tranquility Agreement (BPTA), the concept of the LAC was formalised. However, no maps were ever exchanged and each side had its own version. This led to a number of areas of differing perceptions in Eastern Ladakh and the northeast. Most of these areas were patrolled but not physically secured. And these were the areas in Eastern Ladakh which were preemptively secured by the PLA in 2020 with a hegemonistic intent.

As mentioned earlier, this crisis has led to a de facto delineation of the rival versions of the LAC in Ladakh. The McMahon Line has long been delineated, albeit with differing perceptions. According to reports, as part of the current agreement, two such differently perceived areas in the northeast—Yangtse Ridge, 25 km northeast of Tawang, and Asaphila in Subansiri Valley—have also been formalised and opened for “guided patrols” (a loose term for joint patrols) by China.

In my view, after the current agreement is taken to its logical conclusion, the stage will be set for negotiations toward a broader strategic agreement to formally delineate the LAC along the 1959 Claim Line in Ladakh and the McMahon Line in the northeast, with joint patrolling in areas of differing perceptions. Emotions may run high over such a proposal, but it would simply convert the existing de facto alignment of the LAC into a quasi de jure status. Ironically, the basis of such an agreement would be the proposal Zhou Enlai made in 1959.

Lt Gen H S Panag PVSM, AVSM (R) served in the Indian Army for 40 years. He was GOC in C Northern Command and Central Command. Post retirement, he was Member of Armed Forces Tribunal. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)