In the 7th and 8th centuries CE, medieval adherents of the Hindu god Vishnu intervened in the geopolitical entanglements of Kashmir with the mighty Chinese, Tibetans, and Arabs. They did so through the composition of a sprawling text, the Vishnudharmottara Purana, whose ideas came to be expressed through conquest—both within and outside India—by the famous Kashmiri king Lalitaditya Muktapida.

The word “Purana” might conjure up the image of an eternal, unchanging Hinduism. To us in the 21st century, they seem to be distant, timeless collections of religious stories. But as we’ll see, at the time of their composition, Puranas were profoundly political texts.

Kashmir’s ‘Naga’ kings

In the 6th century, the ancient culture of Gandhara—once the beating heart of an Indo-Iranic world that stretched from Mathura deep into Central Asia—was laid low for the last time. A tremendous earthquake shattered the networks once built by the Indo-Scythians, Kushans, and Huns, and the region’s centres of political gravity shifted to Afghanistan under the Kabul Shahs. The Gangetic Plains came under the successors of the Gupta Empire.

But also rising was Kashmir, hitherto the frontier of the Indo-Iranic world. Its landscape, once dominated by Buddhists and Pashupata Shaivas, was on the verge of a significant change. Within a century after the collapse of Gandhara—around 650 CE—a new dynasty had consolidated power there. This family, the Karkota Nagas, would lay the foundations for nearly a half-millennium of Kashmiri eminence.

According to the inscriptions of the Karkotas, they were descendants of a Naga ancestor—a magical, half-serpent person of the waters. This was a significant claim, since according to myth, the valley of Kashmir had once been an enormous lake, a Naga kingdom. Its draining had left behind many pools and streams, which Nagas were still believed to inhabit. Historian Ronald Inden writes in Imperial Purānas: Kashmir as Vaishnava Center of the World, part of the edited volume Querying the Medieval (2000), that around this time, a Purana was composed in Kashmir, the Nilamata. It exalted a serpentine Naga king called Nila, both as a great devotee of Vishnu and ruler of the valley. It also presented Kashmir’s earlier Shaiva kings as morally corrupt. As such, claiming Naga descent suggested that the human Karkota Naga kings, who also presented themselves as devotees of Vishnu, were set to restore divine order to Kashmir.

Also read: India’s Hindu preachers — How Shaiva monks converted Cambodia

Vaishnavism old and new

We can already see hints above of how Puranas dovetailed with political change, but that was just the beginning. In the early 8th century, the Karkota’s ambitions grew and expanded down to the plains. Here they tussled with the aforementioned Kabul Shahs—Buddhist (and sometimes Hindu) Turks. Soon after, a truly magnificent text makes its appearance: The Vishnudharmottara Purana. Composed by adherents of Pancharatra (Five Nights) Vaishnavism, the Vishnudharmottara focused on the worship of Vaikuntha Vishnu, embodied in images and propitiated with verses and ablutions.

The Pancharatras were originally forest-dwelling ascetics. Their worship of images was on the fringe of mainstream Vedic religious practices, which revolved around fire sacrifice. With the Vishnudharmottara, they sought to incorporate and even subsume Vedic ideas into the worship of Vishnu as the Supreme Being. Central to their faith was the annual five-night celebration of the sleep and awakening of Vishnu before and after the monsoon—the Pancharatra after which they were named. In their view, this had to be performed both by a kingdom’s householders and its ruler in order for it to be blessed by Vishnu. To convince their audience, they wove their ideas into a grand narrative where the sage Markandeya teaches a king, Vajra, in the aftermath of the Mahabharata War.

Strikingly, the Vishnudharmottara used constructions of history, and parallels to its contemporary reality, to legitimise itself. This is similar to how modern politico-religious narratives are justified. At the end of its first book, Markandeya presents a slightly modified version of the Ramayana to king Vajra. He is told that after the coronation of the god-king Rama, the unruly Gandharvas—immortal heavenly beings who ruled in Gandhara—raided the western bank of the Jhelum, where Rama’s co-mother Kaikeyi hailed from. Rama dispatched his brother Bharata, who defeated the Gandharvas and celebrated the sleep and awakening of Vishnu in Gandhara. He then founded the cities of Puskaravati and Takshashila for his sons Pushkara and Taksha and returned home. The Vishnudharmottara is also at pains to explain that Bharata, like his brother Rama, was an emanation of Vishnu.

This might seem purely inconsequential myth, but it is not. Just a few decades prior to the composition of the Vishnudharmottara, the Kashmiris had conquered the western bank of the Jhelum, as well as Takshashila in real-world Gandhara, from the Kabul Shahs. And then-reigning king of Kashmir, to whom the Vishnudharmottara was presented, was named “Vajraditya” Chandrapida. As Inden argues, what the Vishnudharmottara seems to be saying is: The Pancharatra rituals were instituted by an emanation of Vishnu after a conquest of Gandhara in distant antiquity, and taught by a sage to a king Vajra. Should not king Vajraditya follow in their footsteps?

Imperial Vaishnavism

It is very much possible, argues Inden, that Vajraditya had already incorporated Pancharatra ideas into the organisation of his court. In fact, his preceptor Mihiradatta, a Pancharatra master, may have been responsible for much of the Vishnudharmottara’s composition, but not solely. Puranas such as this were composed and expanded across generations. The Gandhara story above suggests that they were made by “complex agents” — Royal courts also played a huge role, directly or indirectly, to shape them. Vajraditya’s ministers, courtiers, and landed elite may have already been Pancharatra initiates; their discussions with their teachers, and the order’s internal discussions and politics, all played a role in how the Vishnudharmottara evolved.

The second and third books of the Puranas hint at this strongly. The second, after narrating stories of legendary Kashmiri heroes granted powers by Vishnu, concludes with a discussion of military tactics to be used to conquer the four quarters of the world. The third book describes how the resulting king-of-kings is to place Pancharatra Vaishnavism at the heart of state ritual by constructing a colossal temple to Vaikuntha Vishnu, with four gateways, for his four faces to look out into the four quarters of the subdued world. As it happens, Vajraditya Chandrapida’s brother and successor, Lalitaditya Muktapida, had a career that corresponds closely to this sequence of events.

Also read: This is how Jains came to dominate Gujarat – grand temples, ascetic monks, spectacular rituals

Final subordination of Kashmir’s ancient Buddhism

Lalitaditya’s ambitions were helped by the geopolitical chaos of his time. Rampaging through the Kathmandu and Kumaon Valleys into the Gangetic Plains, the newly-emerged Tibetan Empire had sacked the older Vaishnava religious centres of Badrinath and Prayaga. Allying with the Chinese and the king of Kannauj, Lalitaditya forced them into submission, comprising a “conquest” of the western quarter of his world. He then turned on his ally and took control of Kannauj, comprising a conquest of his south. According to the Rajataringini of Kalhana, composed in Kashmir a few centuries later, Lalitaditya also forced the “Kambojas” to his east, probably the Turk Shahs, into submission, and routed the Tuhkharas (Tocharians) to his north [Book IV, verses 165–168]. Very much in line with the Vishnudharmottara, then, this Pancharatra king-of-kings had conquered the four directions.

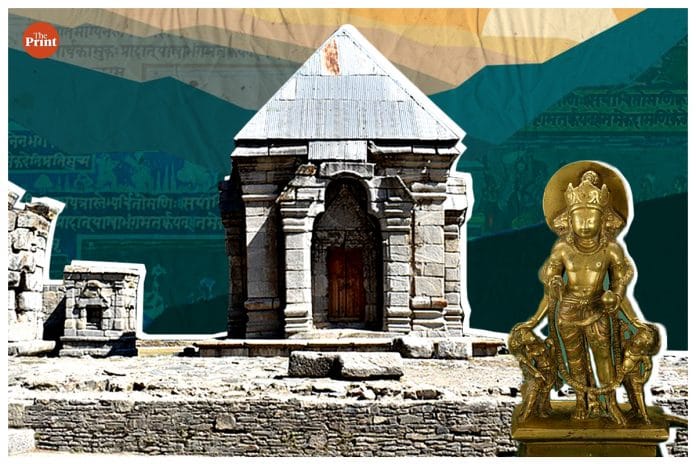

Next, Lalitaditya built a great new imperial city at the confluence of the Jhelum and the Indus rivers: Parihasapura, probably intended as a new Prayaga, since the older one had been sacked. Here he built no less than three colossal temples to Pancharatra forms of Vishnu and a towering victory-pillar surmounted by an eagle. “At least two of these temples,” notes Inden, “appear to have been larger than the other large temple of Lalitaditya that remains standing in Kashmir, the temple of the Sun at Martand.” (Inden 2000, 86). On a lower plateau of Parihasapura were Buddhist stupas, one of them commissioned by Lalitaditya’s Buddhist Turk minister, signifying the final subordination of Kashmir’s ancient Buddhism to a triumphant imperial Vaishnavism. Briefly and brilliantly, the Pancharatrins and the Karkotas of Kashmir thus seized the subcontinent’s centre stage, religion supporting the State, State supporting religion.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval’ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)