The opponents of Hindutva — the non-BJP parties and a section of public intellectuals — have failed to evolve an effective mode to accommodate Muslims in their political projects. There is an elusive search for a counter narrative to Hindutva, which is not fully comfortable with Muslim identity.

Muslims are seen as a victim community to reject Hindutva-driven majoritarianism and anti-Muslim violence. At the same time, there is a conspicuous silence on a few critical issues such as desecration of Hindu temples by Muslim rulers, class and caste divide among Muslims and the nature of Muslim patriarchy.

This intellectual evasiveness produces a weak, unconvincing, superficial and highly essentialist imagination of Muslim presence. It seems that Hindutva’s critique also envisages Muslims as a problem category.

In my view, an alternative imagination of Muslim presence in today’s India is possible that might help us reconstruct an engaging narrative. Two possible avenues may be identified that provide us a few clues for such an intellectual exploration: (a) liberating Muslims from the burden of ruler-centric elite Muslim history, and (b) evolving a moral-political justification for Muslim citizenship.

Also read: Non-BJP Hindu writers are correcting Nehruvian history. With little space for modern Muslims

A Muslim past without ‘Muslim history’

The success of the Ram temple movement has convinced the political class that Hindutva-driven history of medieval India should be accepted uncritically. In fact, there is an effort to refute secular historians completely.

There are two important facts that must be highlighted. First, Muslim communities were not the beneficiaries of Muslim rule. Except the ruling classes, Muslims have always been poor and marginalised. This historical realisation explains why there has always been a power-structure among Muslim communities based on the factors such as class, caste, gender, status and prestige.

Second, Muslims did not follow only one kind of Islam. There were various Islam(s) that evolved through a slow and gradual process in accordance with local customs and beliefs. These slow changes do not usually attract historians because they are trained to rely only on conflicts to understand social change.

The subaltern status of common Muslims during medieval times, and the slow, gradual, peaceful and non-interfering presence of a highly localised Islam give us an opportunity to think of a de-historicised Muslim past.

An argument can be made that the common Muslims, who practice a variety of Islam, are not at all responsible for the acts of Muslim rulers. It is certainly possible that Muslim rulers demolished Hindu temples in medieval period. This very act symbolises a history of conflict, political zeal of Muslim kings, and an apparent misuse of Islam that has nothing to do with the everyday life of Muslims of that time.

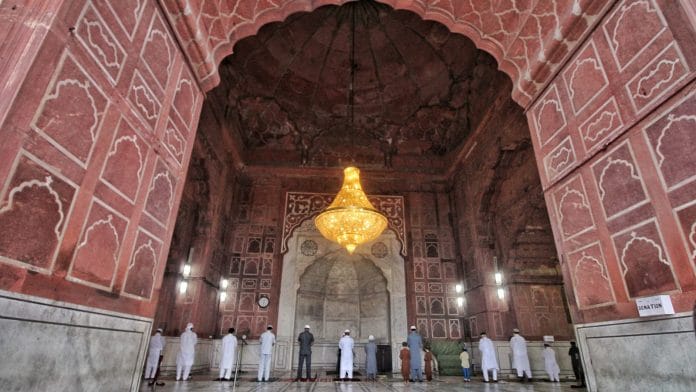

A highly diversified Islamic faith system practised by Muslims in today’s India actually represents a living Muslim heritage — a heritage that does not need any legitimacy from the history of a royal Muslim past. The Hindu women with young children, who gather outside mosques for dua, especially after the evening namaz (Maghrib), symbolise the significance of this shared Islamic legacy.

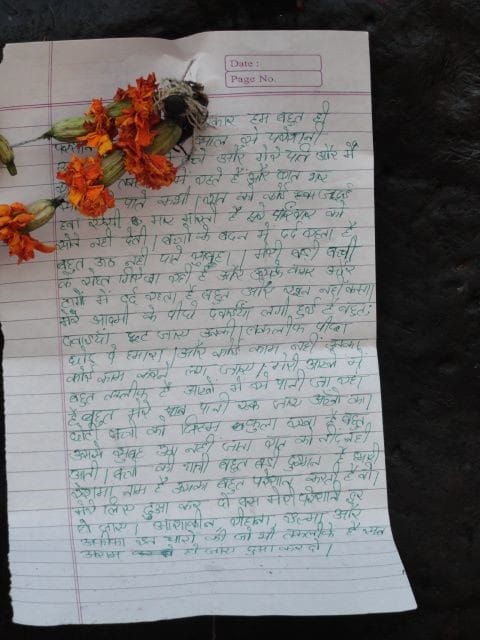

Similarly, the letters written by individual Muslims and Hindus addressing peer baba to solve personal problems at Delhi’s Feroz Shah Kotla also confirm that Hindutva politics does not have the capacity to dismantle the faith of the people, especially Hindus, in the everyday existence of Islam.

Also read: Dear Muslims, don’t take refuge in liberal vs Hindutva binary. These templates are tricky

Muslim citizenship beyond constitutionalism

This brings us to the second possible avenue: the idea of Muslim citizenship. The advent of Hindutva politics in the late 1980s forced the secular elite to recognise the legal-constitutional framework as a viable mode to protect Muslims as a constitutional minority.

This ultimate submission to a particular understanding of constitutionalism somehow has created the impression that the Constitution of India has a capacity to defend itself. Since Muslim citizenship is protected by this legal document, it is assumed that there is no need for any additional political explanation.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA), 2019 has actually proved that the Constitution is subject to multiple interpretations, including a Hindutva reading of it (what I call, the Hindutva Constitutionalism). Interestingly, the opponent of Hindutva as well as Muslim intellectual-political elite are still suffering from a kind of intellectual laziness. They tend to view Muslim citizenship in purely legal terms.

This imagination of Muslim citizenship is pernicious in two ways. First, it has helped the Hindutva politics to silently reduce the CAA-NRC (National Register of Citizens) issue to its desired conventional framework — Hindu victimhood versus Muslim appeasement.

Second, the problems inherent in the CAA are relegated to the margins. No one talks about the fact that the CAA is actually an anti-Hindu law, which makes a migrant Hindu stateless for a period of five years without any promise that he/she would eventually get Indian citizenship!

Muslim citizenship is not entirely a legal phenomenon. Of course, the protection of law is necessary for all minorities and deprived sections so as to assert the membership of the State. Yet, there is a possibility to rethink this question from the prism of actual politics.

The CSDS-Lokniti National Election Study 2019 as well as Pew study on Religion in India 2021 show that the overwhelming majority of Indians believe that India belongs to all communities. This is a very valuable finding that takes us beyond the rigid meanings of Muslim citizenship.

It reminds us that unlike our political class, common Hindus do not see Muslims as a problem category. In fact, the co-existence of different religious communities is recognised as a precondition for being a good Hindu or Muslim. In other words, Muslim identity is primarily seen as an inseparable constituent of Indian identity.

Politics, we must remember, constructs its own versions of past and future. Popular belief and everyday interactions of communities are such political sources that could be utilised for refashioning a constructive imagination of Muslim presence and its placing in India’s past, present and future.

There is an immense possibility to use this living archive. However, it depends on political will and intellectual honesty.

Hilal Ahmed is a scholar of political Islam and associate professor at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), New Delhi. He tweets @Ahmed1Hilal. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)