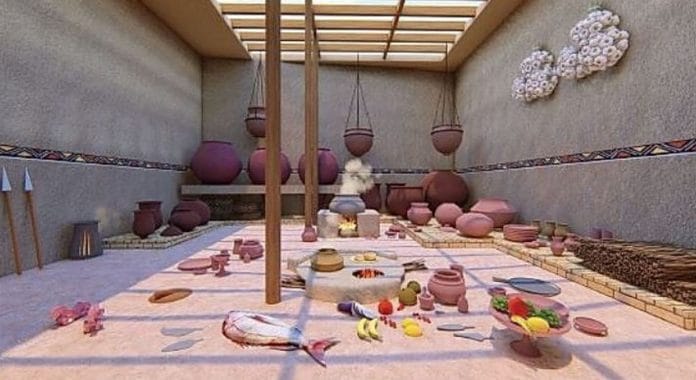

The National Museum in Delhi has been trying to shake off its sloth by doing some blockbuster, headline-grabbing exhibitions in recent years and bringing in external curators. One such attempt was to begin this week with a food exhibition on Harappan kitchens and a tasting menu to give visitors a taste of the Indus Valley Civilisation. It was called Historical Gastronomica.

But in a dramatic reversal, the National Museum barred non-vegetarian dishes from being served last-minute quoting unwritten ‘museum traditions’, the presence of religious idols and relics in the galleries and complaints by two MPs.

In the era of much history rewriting, it must be veg-washed too, apparently. Historical accuracy must take a backseat when you have gods in the galleries.

Gods in the galleries

This isn’t the first time when the 71-year-old National Museum has bumped into the non-vegetarian and alcohol question.

Back in 2002, the museum’s canteen decided to start serving meat dishes on its menu. At that time, the Hindu fundamentalist group Vishwa Hindu Parishad burnt the museum director’s effigy in protest.

The brouhaha was, once again, about the presence of gods in the galleries at the museum. In fact, in 1990 – yes, way before the ascendance of the BJP, the VHP and Narendra Modi – a very dynamic director of the museum, L.P. Sihare, even lost his job because he served alcohol at an event to a visiting Western delegation.

Cultural historian and former National Crafts Museum chief Jyotindra Jain had written: “Of late, the museum in India is increasingly becoming a layered space with resurgent political, social and religious interventions.”

How can alcohol and meat be served in the vicinity of the paintings and statues of gods? Ironically, there are many Hindu temples across India where meat is part of the prayer offering and prasad. But why let facts get in the way of how a museum is run. Especially when people who follow brahminical ideologies shape public debate and public outrage in India. Museums should be, but are never, part of the public debate. A sarkari institution run by babus, they just don’t have an authentic voice.

When I was teaching a course briefly in the National Museum (they offer post-graduate degree courses), I would see staff members enter through the main corridor every morning and head first to the tall Vishnu sculpture to touch its feet. Someone would even place three flowers at Vishnu’s feet. This is why in many smaller history museums, rural visitors actually take off their shoes, like they would at temples.

This museum practice was in contradiction to what I understood from the concept of ‘khandit’, Hindi for broken. Traditionally, Hindu devotees and temple priests would not allow broken statues because they weren’t considered good enough for worship.

Not just Hindu objects, the National Museum displays Buddha’s relics and bone fragments too. Many Buddhists, including the royal families of Bhutan and Thailand, and monks from all over the world visit these relics to pay respect. In fact, many start praying and bowing much before they reach the actual exhibit.

Minister of State for Sports and Minority Affairs, Kiren Rijiju had requested in 2015 that the relics be taken out of the museum and kept in a sacred place so that devotees could offer their prayers comfortably. The museum declined.

Also read: Not just Modi’s museum for PMs, Indian MPs need archives and oral histories too

Whose artefact is it anyway?

Museums around the world have grappled with the question of religious artefacts. Native American communities in the United States had a raging debate on this subject for decades. They said when their objects of worship were displayed in cold, aestheticised vitrines in museums, they lost their sacredness.

This is why native American communities resisted museum takeovers of their culture. Their long struggle resulted in the US Congress enacting the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) to return or treat these objects with dignity and respect.

The communities also protested the curatorial interpretations given to them. Some objects, they argued, had to remain in the dark (in museums, a shaft of light would be shined at them), some were never meant to be viewed by human eyes (in museum’s they would be viewed by millions), and some had to stay buried.

American museums began to address this in different ways. They consulted community elders on how to display and interpret. So, the academic curator lost some of her control. In the Cahokia Mound museum in Missouri, each Native American object had two text labels – one ‘according to elders’, and another ‘according to the curator’. It was an important intervention in the gods-versus-museums debate.

Some such as the Smithsonian National Museum of American Indian, where I worked, even invited elders to come and perform rituals in front of objects in the gallery. There were also some days when an object would be taken out of display and loaned to the community for religious festivities.

One of the biggest attractions and revenue-getter at the museum was the café. Why? Because they served native American cuisine – much like what chef Sabyasachi Gorai or ‘Saby’ was trying to do with the Harappan kitchen exhibit at the National Museum here.

Also read: Not even Rama and Laxman could resist the succulent meat preparations of ancient India

What’s in a museum

I would like to end on a personal note. I used to be a staunch Murugan devotee, before I became an atheist and rejected religion (as a personal and political protest against Mohammed Akhlaq’s lynching in the name of Hinduism in 2015).

In 2013, when I visited the History Museum in Jakarta, a group of Muslim school children and I stood in front of a beautiful, ancient Murugan sculpture. I do remember saying a quick prayer under my breath.

Basically, you don’t like Hindus. Could have saved us the dead brain cells and used 4 words instead of 1400.

Why do bone-headed bigots like you bother to read articles like this? You know everything already, don’t you.

The act of barring meat at this museum is so wrong. Human beings have been eating meat for thousands of years and only in this last century was vegetarian thought to be closer to god than eating meat. People need to let others eat what they want and stop trying to make others eat what they want!

Great and enlightening article. Human nature remains the same all over the world.

Nom-vedic gods are all non-vegetarians..They are stolen into vedic hinduism… Historical mistake is to classify vedic and non-vedic traditions into Hinduism…

Historical mistake is your mom giving birth to you.