In her 2021 book River Kings: A New History of the Vikings from Scandinavia to the Silk Road, archaeologist Cat Jarman talks about finding a small orange bead, nestled with other artefacts, from the excavations in Repton village in England that was conducted between 1970s and 1980s. This rediscovery led her to uncover new facets of Vikings’ history and their connection to the rest of the world.

Jarman’s description of the bead in the prologue instantaneously rang a bell. By the end of the book, she found herself trailing back to a quaint little port town in Gujarat, called Khambhat where the orange carnelian bead was manufactured. This tradition of manufacturing beads was not limited to the Viking Age; it has 5,000 years of documented history that traces back to the Harappan Civilisation.

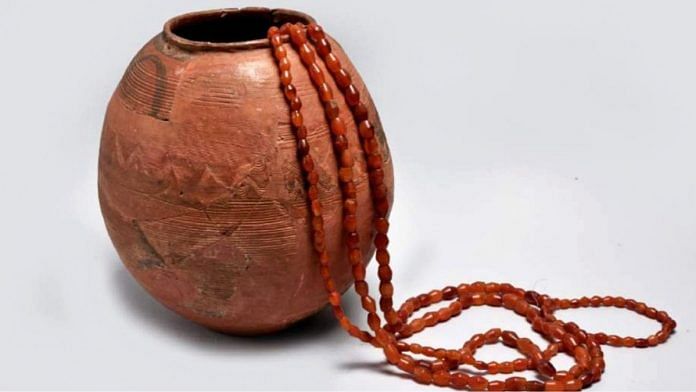

Long barrel-shaped and conical multi-faceted carnelian beads and banded agate beads that went on to become the markers of the Harappan identity were manufactured in Khambhat. It was then traded with the rest of the ancient world. What is fascinating is that craftsmanship of the town’s habitants and finesse of the bead continued to attract traders even after the city lost its identity as a port town in the 17th century. The bead manufacturers got an occupational boost and Khambhat became one of the largest centres of stone bead producers in the world.

Also read: Buzahom can change story of evolution. Until recently it was a Kashmiri T20 cricket ground

Harappan connection

As one of the oldest specialised crafts dating back to prehistory, stone and bead manufacturing has been a significant activity from 10,000 BCE. It played an important role in human culture. From prehistoric beads to polished carnelian or agate beads of 3rd millennium BCE, bead-making as a craft demonstrates the cultural dynamic of the past. Even today, beads show social, economic status and one’s cultural identity apart from being used for ornamentation.

Beads played an important role in the world of Harappans too. They formed a large part of the antiquities in the craft-specialised culture. Carnelian, agate, jasper, lapis lazuli, steatite, etc are few stones that were used in making the Harappan beads that have been recovered from hundreds of sites explored and excavated so far.

It was Indian archaeologist Shikaripura Ranganatha Rao, the excavator of a Harappan port named Lothal, who first spoke about the link between Harappan beads and those from Khambhat. Since Lothal is located about 62 km north of Khambhat, Rao spoke of the similarities found in the bead workshop at both the places. His excavation report suggested that the present-day bead makers of Khambhat are descendants of Harappan craftsmen who continued the 5,000-year-old tradition.

The craftsmanship involved a tedious process that started with procuring raw material and ended with finished polished stone beads. Gujarat sites such as Nageshwar, Shikarpur, Bagasra, and Nagwada focused on the processing of raw materials. Whereas at larger centres like Surkotada, Rangpur, Dholavira, and Haryana’s Rakhigarhi evidence specialised workshops produced beads using new techniques and a new type of cylindrical drill made of Ernestite, a metamorphic rock.

Archaeologists in over nine decades of Harappan studies have recorded stages of bead manufacturing at many sites—from finished, unfinished beads, raw materials, flakes to kilns and hearths. With the rise of Harappan civilisation, the craft became highly specialised in order to meet the rising needs of the urban elite and traders. Along with the production of finer polished beads of hard agate, the larger centres were controllers of trade activities by both land and sea which, as per archaeological records, was spread as far as the Persian Gulf or the Arabian Sea. And more recently, into the history of Vikings.

Also read: Fantastical beasts, sacred motifs—unique Harappan seals that drove Indus valley economy

Lapidary in 21st century

Anwar Husain Shaikh, a resident of Khambhat, is a fifth-generation bead-maker who crafts Harappan-style beads using ancient methods and hand drilling. It is a sacred craft that is passed on from one generation to another. Archaeologically speaking, the craft that Anwar and his predecessors perfected, gives us a rare glimpse of the past intertwined with the present.

Raw materials such as agate nodules, popularly known as Akik, carnelian, jasper, bloodstone among others are procured from rich geological deposits of Gujarat, particularly around Baba Ghor hills in Bharuch district’s Ratanpur. Baba Ghor is considered to be the patron saint of the bead-makers. As the legend goes, he travelled from Africa to the Gulf of Khambhat and settled in the region. It is his descendants, the Siddhis, who supply raw materials to the workshops in Khambhat. Once they reach the workshops, the nodules undergo a series of steps involving drying, heating, chipping, and polishing. The nodules are heated thrice, in between finishing and polishing, in earthen pots filled with sand on monitored heat.

Drilling of beads is yet another interesting aspect of Khambhat bead-making as it replicates the past in its full glory. Beads were drilled with hand-held vises or ‘bethi’. And after drilling half way through it, the bead was turned over and drilled from the opposite side. Today, the hand-held drilling has been replaced with electric equipment.

At present, only a couple of craftsmen master the ancient art of making beads. Therefore, Khambhat, which was once a busy port for traders and travellers such as Marco Polo and Ibn Batuta is now one of the rarest examples of traditions that have survived through thousands of years.

It is pertinent to develop such civilisational practices and raise awareness about the importance of continuing with such traditions in the cultural as well as archaeological records.

Disha Ahluwalia is an archaeologist and junior research fellow at the Indian Council Of Historical Research. She tweets @ahluwaliadisha. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)