There is an ongoing trend in archaeology to focus on the earliest dates and cultures of prehistoric sites. But what matters is the nature of those sites and what it adds to the understanding of the past. Burzahom, which is mentioned in the tentative UNESCO World Heritage List, is a classic example of this prejudice. The site might not be as early as the index Neolithic site of Mehrgarh in Pakistan, which is dated to 8th millennium BCE, but it has the power to change the narrative of linear evolution of cultures in the subcontinent to that of coexistence between early farmers, agro-pastoralists and traders during prehistoric times.

The archaeological site, located in the Srinagar district of Kashmir valley, it brings to light the transition of human habitation from Neolithic period to Megalithic period and to the Early Historical period. The site showcases fusion between the pastoralists and the agriculturists as a result of change in climate during the Neolithic period. The exceptional findings, especially from the neolithic levels, involve splendid craftsmanship into stone and bone tools, unique architectural features that evolved with time and environmental changes, and array of burials displaying unique burial practices of both humans and animals, together help in reconstruction of Burzahom’s story. It breaks the popular notion of isolated evolution of cultures and most importantly of linear progression of history.

From pit dwellings to mud-brick structures

Surrounded by the Pir Panjal Range in the valley of Kashmir, 16 km north-east of Srinagar, Burzahom was discovered in 1939 by H De Terra and TT Patterson of Yale-Cambridge expedition. Then followed the excavations in 1960 by TN Khazanchi of Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). The site was excavated for over ten years till 1971 and a fourfold cultural sequence was noted.

These four periods span from 3rd millennium BCE to 1st millennium BCE and to 3rd/4th century CE. Period I is labelled as Aceramic Neolithic because ceramics, or ‘pottery’ as archaeologists like to refer to them, was absent in the material culture in 96 per cent of the dwelling pits. These underground pits, mostly circular or rectangular, are frequently surrounded by postholes. Steps and arched corridors are also found in the circular pits due to superimposition of pits. These pit chambers might have been used for different functions. Polished bones, stone artefacts, and tools made of antlers and other animal bones were yielded. It was also noted that food gathering was a part of the subsistence pattern with the introduction of cereal farming.

Then came Period II—Ceramic Neolithic phase. As the name suggests, it had ceramics as part of its material culture milieu. As interesting as the findings of this phase were, the archaeologists divided it into two parts, Period IIA and Period IIB. The former, apart from the presence of handmade pottery, yielded a large number of circular pits suggestive of growth in human population. The evidence of domestication of wild animals such as wild dogs, sheep and goats showed the growing sedentary life in the valley, defining the changing dynamics in human-animal relationship.

Period IIB is noted as an interesting one in the life of the people of Burzahom. A distinct change in technology is noted with new tool types—double-edged picks, spindle whorls, spear-head, copper arrowheads, harvesters, celts among other things. Items such as pendants, beads and terracotta bangles suggested cultural and commercial contacts with neighbouring regions of Pakistan, Tibetan Plateau and other sub-Himalayan areas. Dwelling pits too began to be raised above the ground, owing to favourable climatic conditions with an additional use of timber.

One of the most important findings from Period II was the wheel-made vase with a wild goat, which had long horns and hanging ears. The shape of the vase and its design resemble those found in Kot Diji, a pre-Harappan site location in today’s Pakistan. Interestingly, this pot contained 950 carnelian and agate beads, which also point to a close contact with the Harappans.

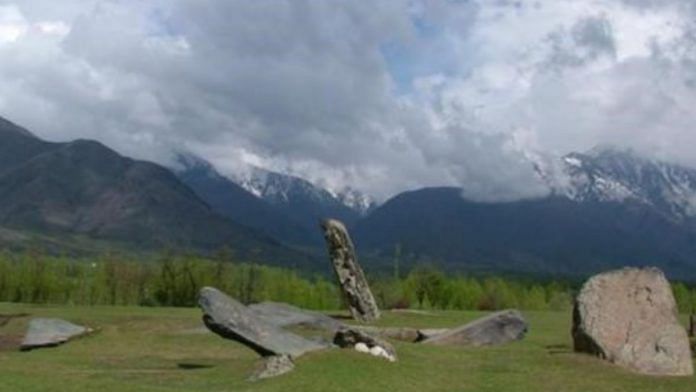

Period III is marked by the Megalithic menhirs. Mega meaning big and lithics are stones, therefore in simple terms they are the big stone structure akin to Stonehenge of England. Megaliths are found in the length and breadth of India except few areas. In general understanding, megaliths are largely associated with southern India. But here in the Kashmir valley, their presence is significant, which goes to show the changing dynamics between humans and their environment, and the growing complexity in the society. The pattern of living in Period III was the same as the Period IIA and Period IIB but with a small exception of rubble masonry, showcasing a gradual transition between the Neolithic and Megalithic periods.

Period IV, which is marked by the beginning of the Early Historical period, had mud brick structures erected directly above the structures of the Megalithic period. Thus indicating continuation of habitation at the site.

Also read: Does ASI protected monuments list need pruning? Historians debate what’s nationally important

Burials of pets and humans

Burial practices at Burzahom are significant due to their stratigraphical and chronological context. During the Neolithic and Megalithic period, circular shaped pits were dug for the disposal of the dead. These pits were narrow at top and wide at the bottom. The burials in the habitational area are mostly below the floor of dwellings, which were later plastered with ‘chunam’. All burials with human and animal remains were oriented in a north-south direction with the skull towards the north. What is interesting is that the bones are found to be treated with red-ochre, which is only possible after the decomposition of the flesh, suggesting re-opening of the burials at some point.

A peculiar practice of burying pet animals with human bones and separate systematic animal burials is noted at the site. Dogs, sheep, goats etc have been buried with the dead. However, mostly pet animals, especially dogs are buried with humans at Burzahom. Known as the companions of humans, dogs were treated with love and care in the society during the neolithic and megalithic period. In the finding of Period II, a dog was buried with the owner under the floor of the house. This interdependent relationship shared between dogs and the people of Burzahom is artistically depicted in the engraving on a stone slab at the site.

Burzahom’s importance has been largely ignored, much like its conservation. Until recently, it was a reputed cricket ground that hosted T20 tournaments. The conservation efforts at the site have finally begun thus it seems the best time to inform the masses about its potentiality. And to urge people to think of a site, beyond early dates, which was largely a farming community co-existing with the mighty Harappans.

Disha Ahluwalia is an archaeologist and junior research fellow at the Indian Council Of Historical Research. She tweets @ahluwaliadisha. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)