Etched in the peace dividend of the post-World War II order, Germany has manoeuvred its national interest in the terrain of neoliberal economics for a long time. Whatever the Germans called their foreign policy, it was essentially an economic policy.

Every time a frozen conflict raised its head, the France-Germany leadership — especially Berlin’s — of the European Union (EU) invoked a neoliberal remedy. When Europe’s security misgivings seethed in Georgia in 2008 and Crimea in 2014, Berlin thought Nord Stream was the answer. For a country built upon war guilt, unlearning military consciousness had become an emancipatory project that treaded only those pathways that were determined by market forces. Even the country’s thriving defence industry had actualised itself along simplistic profiteering, not strategic partnerships.

But Europe again fell under the shadows of war in 2022 with Russia’s war in Ukraine. Not only did the conflict destroy the very foundations of Europe’s post-war order but it also led to an existential crisis for Germany. The German formula for co-opting Russia had not worked. The Nord Stream lay in as many ruins as the disenchanted European dream of lasting peace.

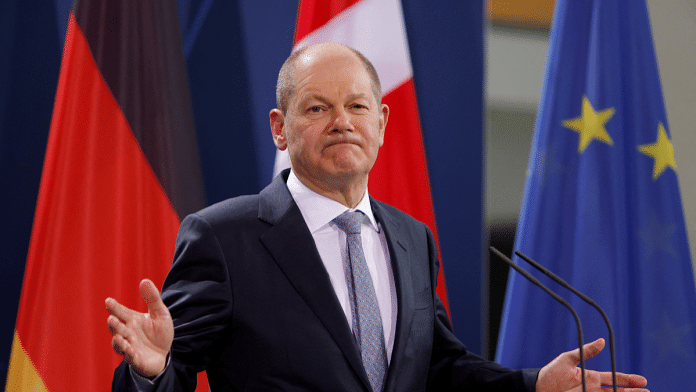

Berlin, at the time, had a new coalition government led by Chancellor Scholz with a promise to embark the country on a path of post-pandemic prosperity. Inherent was a refurbished supply of cheap Russian gas and oil running through the old and new veins of the European economic heartland — just the way it was during the decades of the peace dividend.

But the war and its fallouts highlighted Europe’s structural vulnerabilities in three critical dependencies — for energy on Russia, for the market on China, and for security on the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Also read: NATO knocking on Indo-Pacific door. How India can make the best of this opportunity

Germany’s end of an era

Being the economic powerhouse of Europe and the architect of two of the three dependencies (on Russia and China), German leaders raked their brains for a structural response when the Ukraine war broke out.

First came the awakening that an epochal change — a zeitenwende — is underway and then emerged a series of decisions to complement that shift. But myriad challenges came in the way of devising long-term strategies of securitisation and strategic transformation. Between the awakening and the policy shifts, Germany lay nonplussed in inertia for months, at times appearing reluctant to implement its own decisions for a strategic makeover.

Policymakers in Bundestag, though, had long been aware of how the world was changing. In 2020, Germany felt the first winds of geopolitical and geoeconomic change with the Munich Security Conference giving its special report the title of ‘Zeitenwende | Wendezeiten’. When Russia invaded Ukraine, Chancellor Olaf Scholz reaffirmed his country’s position amid the ensuing global disorder and asserted that a grand strategic transformation was underway. But the announcements followed a period of lull and reluctance as Berlin, despite criticism from its allies, kept delaying the decision on sending Leopard tanks to Ukraine.

Also read: Era of peace for Europe has ended. Future depends on how it deepens its ties with NATO

Mainstreaming security discourse

Although Germany started mainstreaming its security discourse by pledging €100 billion to modernise the Bundeswehr and promising to spend 2 per cent of the country’s GDP on defence in line with NATO demands, a lack of concrete steps made little difference on the ground.

It was only toward the end of 2022 that corresponding policies started to show up. These policies were designed in accordance with three objectives. First, deploying Germany’s defence industrial capacity to bolster strategic partnerships. Second, shrugging off earlier passivity in supporting Ukraine. And third, publishing its first-ever National Security Strategy (NSS) as a masterplan to navigate German strategic transformation.

Boosting ties

The Scholz government has steered its defence industries with a focus on strengthening strategic partnerships with reliable partners across two main security theatres. First, in Europe by strengthening NATO’s capabilities through spearheading the European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI) and with Ukraine. And second, in the Indo-Pacific by enhancing ties with India and Indonesia.

The objective of the ESSI is to boost Europe’s short, medium and long-range air defence capabilities interoperable with NATO and to strengthen Berlin’s air defence capabilities as well. Germany currently only has about 12 medium-range upgraded Patriot batteries but no other short or long-range capabilities. By listing the IRIS-T SLM short-range air defence system (manufactured by Diehl Defence) as one of the three components of the ESSI, the Scholz government is aiming to promote the German arms industry among all participants of the project.

The German defence industry has also entered into unprecedented long-term strategic cooperation with Ukraine. Germany’s arms manufacturing company Rheinmetall has taken concrete steps to engage Ukraine’s State-owned weapons manufacturer Ukroboronprom in a joint armoured vehicle venture with a 51 per cent stake and comprehensive Transfer of Technology (ToT). Rheinmetall has similar plans for establishing joint ventures in Ukraine’s air defence and ammunition as well.

The cooperation between defence industries would have come sooner than later in the course of Europe’s mission to rebuild Ukraine. What is surprising here is the timing (onset of the counteroffensive) and Germany’s open and robust support to Ukraine’s defence industries.

Also read: Russian military showing cracks within. Rise of two private army leaders proves that

Eye on Indo-Pacific

Berlin’s aspirations in securing a free and open Indo-Pacific were apparent in its recent courting of New Delhi and Jakarta. German defence minister Boris Pistorius’s trip to Asia in early June pitched for strengthening partners’ capabilities in the Indo-Pacific.

Germany’s original equipment manufacturer (OEM) Thyssenkrupp Marine Systems (TKMS) also signed an MoU with public sector defence shipyard Mazagon Dock Shipbuilders Limited (MDL) to provide India with sea proven fuel cell air-independent propulsion (AIP) for its P75 I conventional submarine project.

While the project has been delayed for several other reasons too, what is noteworthy is the German minister’s emphatic willingness to strengthen India’s maritime capabilities and help it wean off Russian weapons. There is a corresponding shift in the TKMS’s earlier approach of not showing any interest in joint production and ToT to now when its CEO, Oliver Burkhard, accompanied Pistorius to discuss all possible solutions to take the strategic partnership forward in line with India’s Defence Acquisition Procedure reforms.

Among key initiatives, India’s Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme with an outlay of over $26 billion has made the manufacturing sector more attractive to foreign equity investors.

Pistorius’ visit to Indonesia, too, was all about signalling Germany’s defence industrial support to its partners.

In isolation, it may mean little, but when connected with simultaneous responses by Berlin across the board, it appears to complement the paradigm shift the European power has embarked upon.

And amid such changes is the backdrop of a significant increase in weapons deliveries to Ukraine. Shrugging off its earlier passivity, Germany emerged as an active supplier of weapons to Ukraine just before the start of the latter’s counter-offensive. Criticised earlier for not sharing the military burden of the war, Berlin recently pledged a massive military aid package of $3 billion to Kyiv. Berlin’s active support has been seen as crucial in maintaining European unity and German leadership of Europe.

Also read: Germany’s first-ever National Security Strategy to focus on defence, national security

A half-baked NSS

The Scholz government unveiled its flagship NSS on 14 June. It mentions several steps to be taken along three overarching objectives — robustness, resilience, and sustainability. The document has called Russia “the most significant threat” to European peace and China a “systemic rival”.

While the NSS discusses how to revitalise Germany’s traditional security capabilities, it will be some time till Berlin’s strategic thought matures.

Analysts have been quick to pontificate on the half-baked German strategic approach to the very European security it wishes to bolster. How does Germany plan to address the European management of Russia’s threat without acknowledging the role of actors like the United Kingdom, Poland, or even Italy? Clarity on defence and military deterrence is praiseworthy, but one doesn’t know what the semantics of ‘going together with partners and allies’ would entail if their role and contribution to the European security order are not finding a mention in the 40-page document.

Therefore, hidden under the incipient securitisation ambition are the dysfunctions of the German State.

There is still no blueprint on how a country marred by recession and industrial slowdown will spend the staggering €100 billion committed to its security modernisation. Will it borrow in the short term or raise taxes in the longer term? How will that impact the already bleak German economic performance alongside a sluggish European economy? The German bureaucracy and the decentralised nature of German decision-making are anything but helpful in this regard either.

Perhaps the most important question in the German quest for securitisation will remain unanswered until Berlin’s strategy on critical dependencies on China sees the light of day. The Scholz government’s approach and implementation of its upcoming China strategy will shape the EU’s larger de-risking from Beijing, if at all, and shape the bloc’s economic vicissitudes.

Until then, the German zeitenwende will remain incommensurate with the forces of the zeitgeist.

The writer is an Associate Fellow, Europe and Eurasia Center, at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. She tweets @swasrao. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)