W

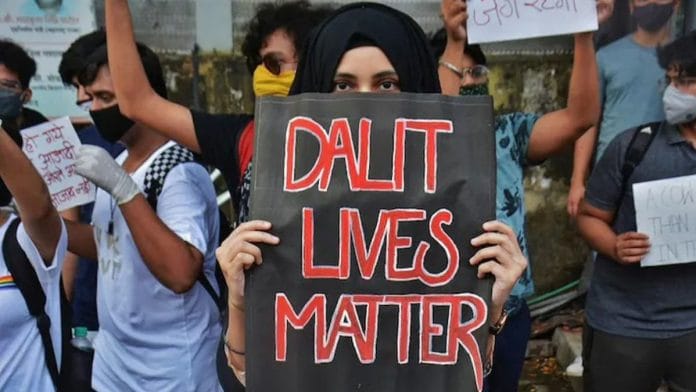

hen India introduced a law to address atrocities against the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in 1989, it came as a beacon of hope, promising protection and justice to these battered communities. But today, even the judiciary seems to be undermining this crucial law.

Relentless violations of human rights and dignity still plague the lives of the most vulnerable. Take for instance, data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), which showed a 45 per cent increase in reported rapes of Dalit women between 2015 and 2020. This is not merely a law-and-order issue— it’s a chronic wound in the soul of a nation advancing in economic growth and global stature, yet failing to heal the deep scars of caste discrimination.

Now, add insult to injury. A few months ago, the Supreme Court observed that the use of “foul language” against a member of the SC/ST community— unless explicitly casteist— was not enough for charges to be imposed under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. In 2018, the court controversially diluted provisions to the law (although amending this the following year) to prevent its “misuse”.

Yet, the distressingly low conviction rates under this Act paint a grim picture of justice delayed and, too often, denied. Under the current government, even the judiciary, a pillar of democracy and justice, seems to be undermining the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. Its remarks on “foul language” can be perceived as attacks on the law designed to protect the oppressed, reflecting the current political climate.

We need to remember that derogatory language against these communities isn’t a minor transgression. It perpetuates age-old stigmas and violates dignity.

Also Read: BJP invokes Ambedkar for poll campaigns but Indian embassies don’t even display his portrait

What a cannibalism verdict shares with SC/ST Act

The use of ‘foul language’ against SC/ST communities is a matter of deep-rooted discrimination. The Indian judicial system, largely a legacy of British colonial rule, still follows laws established during oppressive times, like the 1871 Criminal Tribes Act (CTA), which labelled entire communities as criminal in nature.

This context is crucial for understanding the contemporary interpretation of laws like the SC/ST Act.

When someone uses derogatory terms like ‘thief’ for SC/ST individuals, they indirectly invoke the stigma of the CTA, perpetuating social prejudices.

The SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act in India and the 19th-century Regina v. Dudley and Stephens verdict in England share a foundational connection— their emphasis on certain unwavering legal and moral principles, regardless of extenuating circumstances.

Understanding the implications of the SC/ST Act is crucial, especially in light of recent judicial interpretations. The Supreme Court’s decision to allow states to sub-classify SCs and STs aims to enhance the effectiveness of reservation policies and ensure that benefits reach the most marginalized within these communities.

In 1884, two out of four sailors stranded at sea without food or water decided to kill the weakest member aboard for sustenance. Rescued after 24 days, the men, Tom Dudley and Edwin Stephens, faced trial in England. The court convicted them of murder, underscoring that necessity doesn’t justify taking an innocent life, even in extreme situations.

This landmark decision established that legal and moral boundaries are steadfast, and the law does not condone even acts of desperation that infringe upon these principles.

Similarly, India’s SC/ST Act, designed to combat caste-based atrocities and discrimination, demands a strict adherence to legal and moral standards in the face of deep-rooted societal prejudices.

Just as the Dudley and Stephens case demonstrates that extreme conditions do not excuse the violation of core moral values, the SC/ST Act underscores that there is no justification for discrimination and violence against vulnerable communities.

Both legal narratives highlight the necessity of upholding justice and human rights, regardless of situational complexities. They remind us that law and morality, protecting the dignity and rights of individuals, must be unwavering— whether in the context of a survival crisis at sea or in confronting entrenched societal discrimination.

The struggle of SC/STs in India is a fight for their very humanity. It calls for a collective awakening—a societal shift in mindset, a strengthening of the legal framework, and a relentless pursuit of justice and equality. The cries for justice of the oppressed must not go unheard.

This is a moment for India to introspect, to rise above political and judicial shortcomings, and to reaffirm its commitment to the dignity and rights of every citizen, especially the most vulnerable.

In India’s quest for justice for the SC/ST communities, the principle that every crime matters, seen or unseen, aligns with the essence of human rights.

The author is the president of Foundation for Human Horizon, a UN-affiliated NGO that’s leading the Anti-Caste legislation movement in the USA, and an Artificial Intelligence (AI) Research Scholar at Johns Hopkins University. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: IIT alumni are among global greats. But they are indifferent to Darshan Solanki, Ashna trauma