The recent Cabinet reshuffle was the first big overhaul of ministerial responsibilities in the Narendra Modi government’s second term. Out of 43 ministers who took oath, 15 were new appointees. The Union Council of Ministers now has 78 members, including the prime minister. While a lot has been said about the reshuffle, gender representation in the government needs a special mention.

Gender inequality in executive, legislature, judiciary no better

There are now a total of 11 women ministers in the freshly constituted council – highest in 17 years. Well-known leaders like Meenakshi Lekhi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Anupriya Patel of Apna Dal joined Nirmala Sitharaman, Smriti Irani, and seven others in the Modi government, albeit as junior ministers. The Union executive, however, remains an old boys’ club. Women occupy only 14 per cent of ministerial posts and make up 7 per cent of the Cabinet – a climb down from this dispensation’s own record of having 25 per cent women Cabinet members. In contrast, the average female share in ministerial appointments is 23 per cent across 156 countries.

Comparing the number of ministers might be misleading if women leaders survive longer than men in any role. Of the 12 leaders shown the door by the PM, 11 were men. Yet, over the last three decades, female leaders occupied any Union ministerial post for only 11 per cent of the time, and a Cabinet rank for 7 per cent — similar to their headcount numbers.

The political executive is not alone in missing women. Even the central government bureaucracy is dominated by men. A parliamentary reply revealed that only 11 per cent of the over 30 lakh Union employees were females. Globally, women make up 26 per cent of national legislatures, but the 17th Lok Sabha has 14 per cent women MPs representing almost half of our population.

India’s judiciary is often seen as more ‘enlightened’ than the executive and the legislature. But it scores even worse on gender equality. Since 1950, only 3 per cent of Supreme Court judges have been women. The current vacancy-riddled SC is also a male fiefdom with 26 men among 27 judges. High Courts perform better with 12 per cent representation of women among sitting judges — but lower courts have more than twice as much at 28 per cent. Clearly, women face a harder climb up the judicial pyramid.

Also read: Past Yediyurappa loyalist, firebrand Delhi MP, key UP ally — new women ministers in Modi govt

‘Softer’ portfolios, often excluded from economic ministries

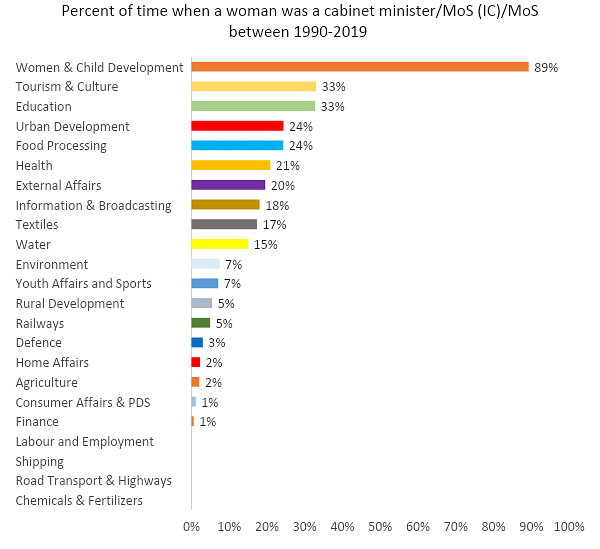

Gender inequality manifests not just in missing women ministers. Data compiled by researchers at the Ashoka University’s Trivedi Centre for Political Data (TCPD) on profiles of Union ministers between 1990 and 2019 suggests that women not only find it more difficult to enter exalted political circles, but also end up being siloed in certain ministries. Expectedly, these include women and child development (WCD) and social justice and empowerment, where a female leader was in office for 89 per cent and 31 per cent of the ministerial time, respectively, including Cabinet and other junior ranks.

Other verticals with significant female participation were tourism and culture (33 per cent), education (33 per cent), urban development (24 per cent), food processing (24 per cent), health (21 per cent), external affairs (20 per cent), information and broadcasting (17 per cent), and textiles (17 per cent). Among Cabinet ministers, however, health and education only had a 5 per cent and 7 per cent female representation. Thus, even within ministries, men were more likely to get senior roles.

There is nothing wrong with women bagging any of these positions. Indeed, given how important health and education are for India’s future, it is pleasing to see our ‘naari shakti’ playing a major role in setting their agenda. But is it only a coincidence that this list excludes hefty economic ministries like finance, defence, heavy industry, railways, transport, and agriculture that corner most of the government’s budget? Before Nirmala Sitharaman came along, women weren’t even getting an MoS position in the finance ministry. Moreover, labour and employment, chemicals and fertilisers, steel, road transport and highways, and shipping, all have had zero ministerial participation of women since 1990.

Urban development and food processing are exceptions to this pattern. Four women occupied 24 per cent of the ministerial tenure in the former portfolio, all in Congress governments. On the other hand, only two women — Harsimrat Kaur Badal and Sadhvi Niranjan Jyoti — were ministers in food processing, both during Modi 1.0.

Also read: PM Modi’s new team is a governance reboot tempered with politics

Must correct imbalance in portfolio allocation

Persistent skewness in portfolio allocation over three decades is concerning. To ensure that women don’t have only a token representation in governance, they must get an equal chance to also lead the ‘meatier’ ministries. The presence of late Sushma Swaraj and Nirmala Sitharaman in the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) was hailed because it showed national security was not the sole preserve of men. It also reaffirmed what we already knew — that women belong in all sectors and roles.

Moreover, many economic problems have an inherent gender dimension. At 20.8 per cent and declining, India’s dismal female labour force participation rate should generate regular outcry. Yet, we have not had a woman minister in the employment ministry in three decades, against 21 men (the latter figure includes only those who served for at least six months).

Finally, leaders helming economic ministries disproportionately influence political outcomes for their parties. Women have a greater chance of winning public support and, consequently, public office, if they acquire proven experience of delivering on what the electorate cares about the most, which are often core economic issues.

The Modi government made some right noises in this reshuffle. Anupriya Patel became the new MoS in the Ministry of Commerce and Industry and Shobha Karandlaje a junior minister in agriculture. Sadhvi Niranjan Jyoti continues as MoS in rural development but got additional responsibilities in consumer affairs and public distribution. Darshana Vikram Jardosh will work with Ashwini Vaishnaw in railways. In all, 65 per cent of the Union budget will go to ministries that have at least one woman political leader. More Cabinet appointments would have been welcome, of course, but given the silos under which female leaders have operated for several decades — and how rare positions in economic ministries are for them — these allocations are praiseworthy.

The author is a researcher at the Poverty & Equity Global Unit at the World Bank and an economist from Oxford University. He tweets @sarthak13agr. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)