Afghanistan, they say, is the graveyard of empires. Central Asia, if we look at the archaeology clearly, is the graveyard of unitary nationalist histories. Perhaps no people exemplify this as much as the Sogdians: arguably one of the most influential diasporas in human history, on par with or even surpassing India’s own.

In the 7th century CE, the city of Kabul was home to Hindu Turk Shahs. If you were to travel to its north, across the Oxus (Amu Darya) river, you would come across a scattering of city-states, squabbling and trading with each other and the world. Within them you would meet the Sogdians, who were Buddhists, Mazdaists, Zoroastrians, Christians, Jews; alongside them were diasporas of Central Asian, South Asian, West Asian, or East Asian descent; they spoke a babble of languages, primarily Iranic, but with many Indic loan words. These forgotten people remind us, as always, that the past was a world without borders.

In the shadow of the Kushans

To understand the Sogdians at their peak in the 7th–8thcenturies CE, we need to first see them when they were insignificant nobodies, 500 years prior. The Kushan imperial network, which we have visited in previous editions of Thinking Medieval, was a great force through much of the Gangetic Plains, Afghanistan, and parts of Xinjiang. They controlled the origin points of trade networks that stretched from the Indian Subcontinent into Persia, the Roman Empire, and into distant China. Overland trade to China was conducted by skirting the Taklamakan desert, either from the north or from the south.

Trade over the desert was a risky endeavour. Historian Valerie Hansen notes in The Silk Roads: A New History that it generally consisted of valuable commodities in small volumes. But such commodities could still generate enormous profits: as Judith A Lerner and Thomas Wilde put it in their exhibition notes for the Smithsonian Institution, they were among the most demanded items in the ancient world, such as “horses from the Ferghana Valley, gemstones from India, musk from Tibet, furs from the steppes to the north”.

The “brilliant urban civilisation” of the Kushans, according to historian Étienne de la Vassière in her magisterial Sogdian Traders: A History, quite outshone the “very mediocre situation” in Sogdiana—roughly the region corresponding to present-day southwest Uzbekistan and eastern Tajikistan. Sogdiana was somewhat of a backwater, situated off to the northeast to the trade routes that led across the Taklamakan Desert. At the time, Kushan merchants dominated the trade in horses in the 2nd century CE, appearing as far afield as China and Southeast Asia. But Sogdian traders also began to participate in the same networks, immigrating and putting down roots in Kushan cities while maintaining ties to their homeland.

de la Vassière notes that when the Karakoram Highway was built between present-day Pakistan and China, enormous amounts of Sogdian graffiti were discovered, suggesting that they were settling in the upper reaches of the Indus River by the 3rd century CE. One interesting bit of graffiti is a prayer by a Sogdian merchant to a local spirit, asking for protection so that he could visit his brother safely. Such family networks allowed Sogdians access to capital and market information and gave them a competitive advantage over other groups.

At the same time, Sogdians also began to appear in China. In A Silk Road Legacy: The Spread of Buddhism and Islam, historian Xinriu Liu points out that the earliest Buddhist monks in China were not native Indians, but Sogdians. In the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, they were working in China, translating texts from Sanskrit into Chinese. de la Vassière notes that Buddhism was not a major force in Sogdiana at this time, and so these Sogdian Buddhist monks were most probably members of merchant families who had settled in India, where they had absorbed both Buddhism and Sanskrit before moving to China.

Also read: A medieval Malayan king beat Cholas at their game. Almost created a superpower

Hindu gods in Samarkand

While the concepts underlying Indian gods were quite ancient, they were never static entities. They were worshipped and patronised by diverse groups, and these impacted their evolution. We can see this process quite clearly for Buddhism, and the same phenomenon applied to its contemporary religions as well, including Hinduism.

For example, the militant Kushans preferred to represent Skanda as Mahasena, literally “Great General”. The Sogdians, as part of the Kushan milieu, were exposed to these pluralistic pantheons, and brought them back to their cities. Their religious traditions melded their local Iranic fire-worship with new imports, maintaining the distinctive Sogdian identity. To illustrate all this, consider Samarkand in present-day Uzbekistan—once the greatest of Sogdian city-states. Drawing on the testimony of the famous Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang, Liu argues that in Samarkand, the Buddha was honoured with processions of torches and firebrands.

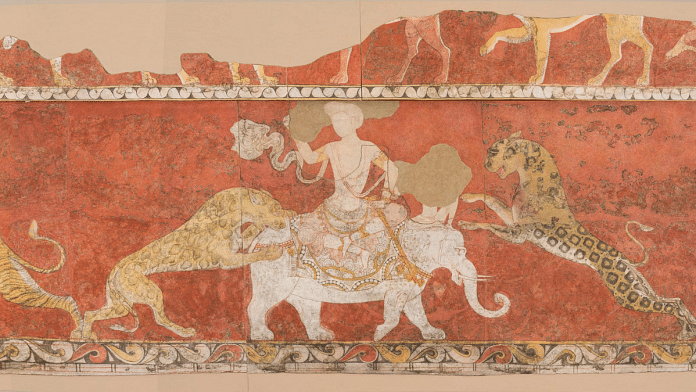

Though the Kushan empire had been torn apart by the 4thcentury, Sogdian diaspora networks outlived it, and only continued to grow in prominence. By the 7th–8th centuries, they were the dominant foreign traders in China, and Sogdian costumes and dance forms were all the rage in the cosmopolitan cities of Tang Dynasty China. By this point, there were also significant South Asian diasporas in Sogdiana, and Indian monks had begun to have prosperous careers in China. The prosperity of Sogdiana can be seen in the mansions of wealthy merchants. Elaborate frescoes of gods, myths, and even Panchatantra stories offer a glimpse into their imaginations.

Sogdian engagement with foreign gods was, in many ways, the mirror of the imperial Kushan dynamic. While Kushan appropriation of Indian gods was driven by the imperial court, in Sogdiana it was a decentralised process, being driven by diverse merchant elites. While Kushan conceptions influenced gods worshipped in India, Indian conceptions instead influenced gods worshipped in Sogdiana.

The Zoroastrian gods of the Sogdians had many attributes, and the by now well-established Indian sculptural norm of multiple arms and faces provided a model to represent them in all their splendour. In Iranian Gods in Hindu Garb, art historian Frantz Grenet cites Buddhist Sogdian texts which mention composite deities such as “Brahmā-Zurwān, Indra-Adhvagh, Mahādeva-Wēšparkar”. Their iconography was primarily derived from Indian models: “Brahmā-Zurwān has a beard, Indra-Adhvagh a third eye, Mahādeva-Wēšparkar three faces.” This last god follows on the lines of the ancient Kushan composite deity, Oēšo-Śiva, and is similarly a composite of a cosmic wind god with the supreme Shiva. In Panjikent in present-day Tajikistan, another major Sogdian city, Mahādeva-Wēšparkar was depicted blowing a horn with one of his three faces, making the connection to wind especially clear.

These borrowings could be dizzyingly complex—not intentionally, but rather as an organic assimilation. Layers of borrowings, in all directions, built up century over century. Grenet argues that in some cases, motifs moved from Gangetic to Kushan to Persian contexts before arriving in Sogdiana.

As a result of all this, 7th century Sogdian may not have necessarily thought of these motifs, these composite deities, as “Indian” or “foreign”. From their point of view, this was just how gods were represented. To them, these models were very much local ones, native to their cosmopolitan world. It is only with modern eyes, accustomed to linking one religion with one language with one people with one region, that the Sogdian pantheon seems particularly strange to us. But the silent frescoes of the dancing Shiva in Panjikent, or elephant-riding gods battling tigers and leopards, in Varaksha challenge us to see this ancient world beyond nationalist sentiment. Connections like this, though they do not reinforce modern political notions of superiority or exclusivity, make the world of our ancestors (and by extension, our own) infinitely richer.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords Of The Deccan: Southern India From Chalukyas To Cholas, and hosts The Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval’ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Prashant)