Vogue Arabia decided to make history this month by featuring three Black hijabis on their cover. What does it mean to see people who look like you on TV, on social media, on magazine covers? What would it feel like to see them accepted, normalised, celebrated even; not demonised — for once? For a lot of Muslims, this isn’t even a remotely familiar experience. One can only imagine how much worse it is for those who have grown up Black and hijabi.

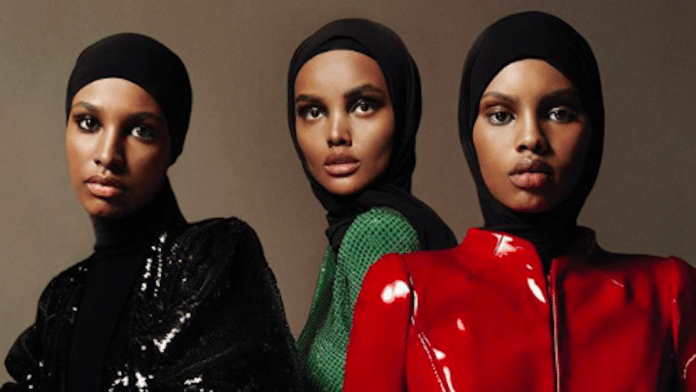

The April issue of the Vogue magazine features models Halima Aden, Ikram Abdi Omar, and Amina Adan and focusses on “shattering stereotypes”. While this isn’t the first time a model donning a hijab has been featured on the cover of the magazine, this particular cover is being applauded for acing the messaging as well as for having a group of women on its cover. “To think that just three years ago there was not a single Hijabi model and now fast-forward to the first Vogue Hijabi group cover,” wrote Halima Aden who has graced the magazine’s cover for the second time.

Two years ago, American supermodel Gigi Hadid faced tremendous backlash for wearing a hijab in her photoshoot featuring on the cover of Vogue Arabia. Hadid extolled her “half-Palestinian” roots while promoting that cover, but readers didn’t buy it. Appropriating an attire that often not only invites violent Islamophobia, but is also deemed ‘oppressive’ when worn by practicing Muslims — and then celebrated as ‘art’ when used as a costume — is extremely hypocritical and hollow.

Also read: My dress trolled because I’m a woman, says Shehla Rashid after Twitter slams hijab look

It is symptomatic of the mentality that refuses to see hijabi Muslims as anything but that. So, it doesn’t matter if you are elected to the US Congress, it doesn’t matter if you become a bronze-winning Olympic fencer, and it most definitely doesn’t matter if you get killed for your identity. The problem will still be you: your clothing, your lack of agency, your conditioning. The manner in which the hijab and hijabis are often made into spectacles makes one thing abundantly clear — everyone loves a young (hijabi) woman who can be rescued, everyone loves a project.

Interestingly, social media deep dives into a collective discussion on hijab almost once every month, because what better intellectual stimulant than analysing clothing you don’t know anything about, instead of the ones you wear everyday that will somehow never be a result of ‘conditioning’, always choice.

Something tells me it’s that time of the month again.

Choice and the lack thereof

Less than half a month ago, New Zealand witnessed deadly terrorist attacks on a mosque in Christchurch during the Friday prayers, killing at least 50. In what was a remarkable act of courage, solidarity and most importantly, leadership– the country’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern decided to don a hijab and say, “We are one. They are us.”

This was followed by many in New Zealand, including TV anchors donning the hijab to make a point. A point that many seemed to have missed.

“How could she do this when women in Iran and Saudi Arabia are forced to cover up?” some wondered in angst. Precisely because the values that New Zealand stands for would not allow for women to be singled out either for wearing something or for not wearing something.

The hijab isn’t purely co-incidental to Islamophobic attacks — it is often what drives them. To casually ignore that driver, even when a white supremacist leaves no space for doubt by meticulously writing a manifesto before the attack, is nothing short of naïveté.

Interestingly, though, this conversation on ‘conditioning’ takes the centre-stage only and only when the subject being discussed is a hijabi woman. Never so much when magazine cover after magazine cover objectifies women in clothing and via poses meant to reduce them to less-human and more-object.

Also read: Hijab not simply about religion, Muslim women wear it for several reasons

The best kind of questioning, the truly rebellious kind, however, wouldn’t even be that. It would be the kind that requires us to look inwards: Why am I wearing a saree? A saree meant for the very purpose of covering me in all of six yards. The kind of questioning that will not cause us to quickly defend certain manifestations of a religion as nothing but ‘culture’, but will make us realise that often culture is a derivative of religion.

Why am I wearing make-up everyday without fail — something that entails me transforming something as basic as my face? What is this patriarchy that won’t let me step out with my face without plastering it with cosmetics?

But such questioning would require us to let go of our patronising behaviour and paternalism, it would require a kind of self-reflexivity that goes beyond looking at anything ‘other’ with scorn.

“Patriarchy is back in ‘Vogue’,” a tweet read in reference to the Vogue Arabia cover.

Hate to break it to you, but patriarchy never stopped being in vogue. Introspective ability and self-awareness did, perhaps.

Let me clarify. I was a saree wearing woman all my working life. And non saree wearing in my retired life! So this is not about tradition or orthodoxy or even prescription ? But really? saree is meant to cover all of the body? Hardly ever. Midriff bearing and hipster saree were around even in my youth in the 1960s. And necklines that got deeper as the years went by. And now it is a fashion statement in its various avatars. The saree (and the dhothi with top cloth)) suited our climate well..well ventilated and yet with enough give to cover the face and body against the harsh sun. Indian women have been smart enough to hold onto it while Indian men have succumbed to western clothes meant for colder climates. Agree with Tejas that this is a rather dated argument. Need better nuancing from our journalists. Agree with you though that all of us need (self) reflexivity to realize how much we ‘normalize’ ourselves in our minds while yet judging others. Needs great skill though!

I have not understood the author’s problems with the Indian saree. No women is forced to wear a saree. There are many working women who do not wear sarees and even wear pants to work. It is left to the functionality of the dress and the women are free to use it. The saree has no religious connotations and is mostly worn in South & East India.

How much a woman exposes her body while wearing a saree is entirely based on their cultural traditions as well as her own body type and choices.

The author does not seem to be aware of the various methods of saree wear and how the saree can be modified in a jiffy to look sexy and alternatively dignified which has been shown in many art forms.

Do not compare the saree with the hijab or burqah. Just goes to show your own bloody ignorance and how much you have been brainwashed by your own religion about other religions.

All through the recent tragedy, PM Jacinda Ardern acted with compassion and empathy, standing out on a global stage because these qualities are becoming a little rare in public life. Wearing a hijab when she visited the families of the victims, to offer condolences, was a very gracious act. The Muslim world is changing, most of the orthodoxy will be gone in the next fifty years or so, but it is for the community to decide the pace of change.

Wow, this would be a brilliantly insightful article in the early to mid 1900s, when sarees and make-up weren’t questioned or problematised. Both are today extensively questioned and recognised as being just as oppressive… Although the author’s weak attempt at asserting equivalence between those things and hijab by saying “culture is a derivative of religion” does not hold up because certain versions of Islam (a religion) prescribe clothing, which Hindu/Christian scriptures don’t in terms of saree or make-up (hence the prescription is cultural; regressive, but cultural).

Anyhow, it’s not “social conditioning” that makes women in Iran or Saudi Arabia “cover up”, is it? It’s the existence of a theocratic State that claims allegiance to Islam. To sweep this under the carpet (at least in this particular article) suggests that the author is guilty of the naiveté she accuses others of.