From extraction and production to the manufacturing and supply chain—China is an ever-present entity in the conversation about rare earth elements today. In fact, it awakened the world to the geopolitical and strategic use of rare earths in 2012. Since then, Beijing’s resource diplomacy has been shaping individual, bilateral, and multilateral initiatives globally. But in the past few years, this monopoly has been declining.

Rare earth mines in Myanmar, Madagascar, Greenland, the Pacific Ocean and Afghanistan are ones that China has invested in to maintain its stronghold. But its initiatives and efforts to sustain its monopoly need further investigation.

Chinese rare earth monopoly

China’s entry into rare earth politics began through the Sino-Soviet Industrialisation program in 1956 when Russia began to develop trial alloys in China to develop its own aircraft and ballistic missiles. When China conducted its first nuclear weapons test in 1964, it also realised that it needed to develop its own rare earth industry. China’s major deposit, the Bayon Obo, has both bastnaesite and monazite minerals, which enabled it to deal with the regulatory constraints and fill the gap when the US industry declined in the mid-1980s. The main credit goes to Dr Xu Guangxian, called the ‘Father of China’s Rare Earth Industry’. It was his discovery of the ‘cascade theory of countercurrent extraction’ that revolutionised rare earth production and marked the beginning of China’s technological superiority in the sector. China’s monopoly over the value supply chain began in the 1980s and Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 statement: “The Middle East has its oil, China has rare earth (中東有石油,中國有稀土),” reflected its dream of becoming a leading rare earth producer.

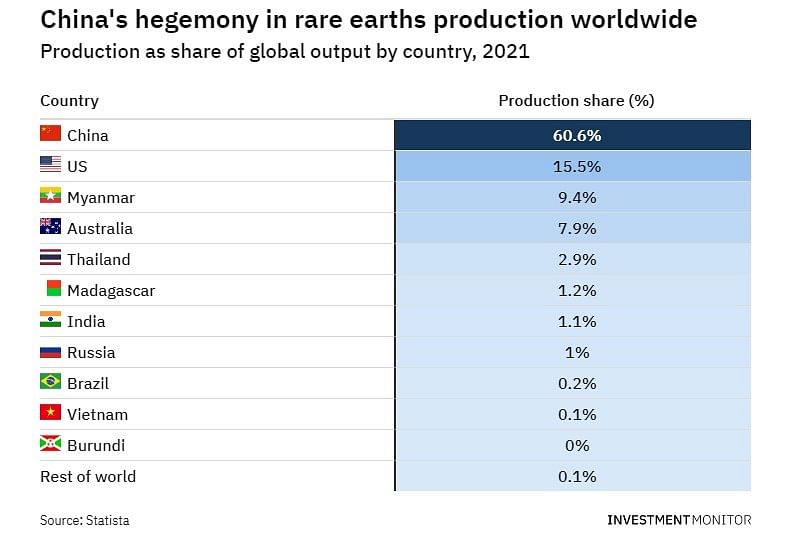

China’s high production and export capacity has aided its geopolitical and economic development around rare earth minerals. These advancements have made the world increasingly dependent on Beijing to the extent that they fear a Chinese embargo more than a military conflict. The Senkaku-Diaoyu Islands dispute that started in 2011, is an example of what Xi Jinping’s country is capable of.

The dependence of developed countries like the US, Japan and EU nations on Chinese rare earth elements (REE) is connected to their need to manufacture defence equipment, particularly drones, and commitment to clean technologies such as electrical vehicles and wind turbines. In fact, in 2019, the US imported 80 per cent of its rare earth minerals from China, as reported by the US Geological Survey. Meanwhile, the European Commission reported the import of 98 per cent rare earth supplies from China in 2020.

Also Read: Rare earths, their strategic significance, China’s monopoly & why it matters to the Quad

Managing the monopoly

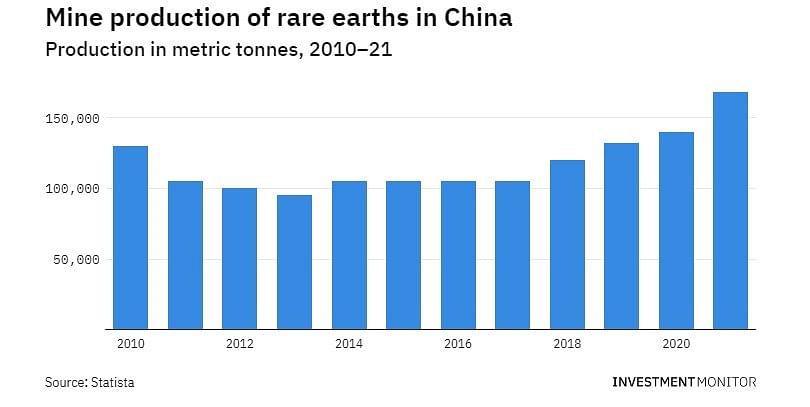

Chinese rare earth monopoly can be attributed to three major factors: advanced economic statecraft; cheap labour availability; and non-existent environmental laws. Research and innovation programmes like Program 863 and 973 gave China the push to modernise its rare earth sector. It even launched multiple policies and plans, as a result of which, China dominates all aspects of REE supply chains—production, processing, and research and development. It has developed thirteen rare earth deposits, 44 million metric tons of reserves, and a production capacity of 14 million metric tons. In addition, the Chinese government has been shifting towards cleaner production of rare earths with greener hydrometallurgy and elimination of wastewater discharge containing thorium or radioactive solids.

Molycorp Mountain Pass deposit (US), Lynas Corporation Limited (Australia), Norra Karr (Sweden), Kvanefield and Kringlerne (Greenland) are alternatives trying to compete with China’s rare earth industry. But they need more than 15-20 years to reach their potential. In comparison to Chinese industries, they acquire mostly light REEs. Moreover, these companies are still competing with their thorium-uranium levels and financial problems.

With a focus on enhancing research and development, China has developed two key laboratories working on rare earth elements: The State Key Laboratory of rare earth materials chemistry and applications at Peking University and the State Key Laboratory of rare earth resource utilisation at Changchun University. Besides, China is the only country that has journals with a specific focus on rare earth—the Journal of Rare Earths—under editor Xu Guangxian; and the China rare earth information journal under scientists.

Also Read: The Chinese are digging, but it’s no Jurassic Park. The Pacific hides other treasures

Global concerns

The world, particularly high rare earth import-dependent countries, increasingly became concerned about the Chinese monopoly after two major events.

First, is the China-Japan Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands Conflict.

China restricted exports of critical REE minerals to Japan in response to the detention of a trawler captain, affecting the auto industry of Japan, the largest importer of REEs. Though China didn’t issue an official statement, its resource geostrategy was taken as a serious threat by the US, EU and Japan. They filed suit in WTO, which ruled that China could not put limits on REE exports. But the ruling came four years later, and China denied the accusation, claiming that the action was to preserve the REEs for its own industries.

The second event is the US-China trade war.

In 2018, then-US President Donald Trump accused China of violating the intellectual property rights of US companies and imposed tariffs on Chinese tech companies, including Huawei, in May 2019. But the most important part of China’s retaliation was the embargo on the exports of rare earth metals and their compounds. The People’s Daily had then written: “We advise the U.S. side not to underestimate the Chinese side’s ability to safeguard the development rights and interests. Don’t say we didn’t warn you.” This reflected China’s confidence in its monopoly over the REE supply chain and how it could use rare earth metals as bait to negotiate its demands.

Also Read: The West is tired of China’s power games. India could take advantage

Sustaining efforts and initiatives

China’s declining reserve and production capacity share from 70 per cent in the 2000s to only 38 per cent in 2020 has been motivating its geo-economic engagement in resource-rich countries with poor economies to sustain its monopoly.

China’s major rare earth geo-economic investment is in Madagascar, which has the sixth-largest reserves of rare earth elements. According to Reuters, in 2019, a unit of China Nonferrous Metal Mining Group (CNMC) signed a non-binding memorandum with Singapore-listed ISR Capital that could see the Chinese firm work as a contractor on a rare earths project in Madagascar. It will have the right to purchase 3,000 tonnes of rare earth products within three years of the start of production and the opportunity to make an equity investment in future.

Similarly, China is also showing interest in Afghanistan’s mineral industry. Former PLA Colonel Zhou Bo wrote in The New York Times that “With the U.S. withdrawal, Beijing can offer what Kabul needs most: political impartiality and economic investment. Afghanistan in turn has what China most prizes: opportunities in infrastructure and industry building — areas in which China’s capabilities are arguably unmatched — and access to $1 trillion in untapped mineral deposits, including critical industrial metals such as lithium, iron, copper and cobalt.” However, there is no progress in their mineral relation till now. Chinese companies have also made moves into overseas rare earths. Reuters report says that Leshan Shenghe Rare Earth Co, a unit of Shenghe Resources and the largest shareholder in Greenland Minerals and Energy, is seeking to develop the Kvanefjeld rare earth project in Greenland. Recently, China’s Sinomine resource group launched a $200 million project to build a plant and expand existing mining operations at the Bikita lithium mine in Zimbabwe, which President Emmerson Mnangagwa saw as an opportunity to develop the nation as a major player in global battery minerals supply chain.

Though these initiatives are under-progress and are not as developed as the Belt and Road Initiative, they are still important in the context of China’s reducing capacity reserves and the growing global efforts to reduce dependence on Beijing. Will China manage to sustain its monopoly or lose it to its contenders like the US or Australia? Only time will tell.

Neha Mishra is a Research Associate (Indo-Pacific Group) at the Centre for Air Power Studies. She is doing her PhD from the University of Delhi on ‘India-China Geo-economic Engagement’. Views are personal.

(Edited by Srinjoy Dey)