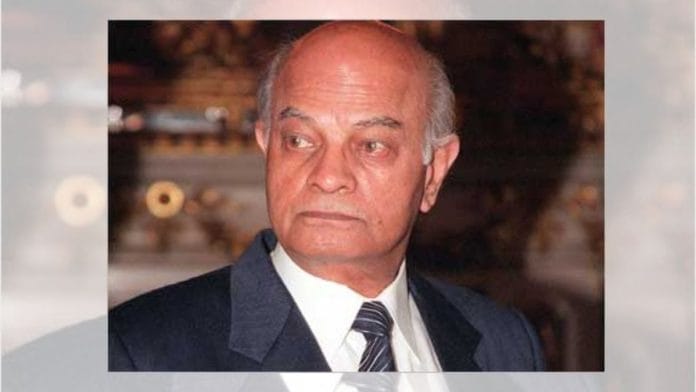

With a tenure of six years and 64 days, during which he concurrently held the charge of National Security Advisor for five years and 85 days, Brajesh Mishra of the 1951 batch of the Indian Foreign Service has undoubtedly been the most powerful and influential principal secretary of any Prime Minister’s Office. None before or after him combined the two powerful positions.

In 1991, a few months before his superannuation, Mishra joined the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and headed its foreign affairs cell, even though his father, DP Mishra, had been the formidable chief minister of Madhya Pradesh as a Congress leader. As the BJP’s foreign policy spokesperson, Brajesh Mishra had unequivocally made it known that if elected to power, the party would work to build a nuclear bomb.

When Atal Bihari Vajpayee was sworn in as the Prime Minister on 19 March 1998, Mishra was appointed as principal secretary to the PMO the same day. He moved ahead “full steam” with the nuclear programme, ensuring India conducted successful nuclear tests within weeks of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government taking office.

Mishra had to ensure that the veil of secrecy was maintained until the completion of the tests. An India Today report aptly summed up the situation: “Mishra first made it so on May 11, 1998, by being the only man in the Government to address the media after the Pokhran blasts. According to the PMO, he did it on Vajpayee’s instructions. It set the tone of an uninterrupted innings that has divided the Government, strained Vajpayee’s relations with his party and the Sangh Parivar, and created an image problem for the Government.”

Also read: Indian economy would’ve liberalised long before 1991. But Bofors scandal stalled it

Beyond Pokhran

From being closely involved in the planning of Pokhran tests to pushing for deeper engagement with the US and attempting to mend ties with both Pakistan and China, Mishra stepped out of the bureaucratic mould to implement the broad vision of foreign policy sketched out by the Vajpayee government. Mishra was rightly described as the first (and only) foreign policy Czar who always had the final word on diplomatic and security-related questions. Thanks to his foresight and perspicuity, India was able to reverse the commitment made by LK Advani and Major Jaswant Singh to send Indian troops for the US-led coalition against Iraq.

Mishra was no ideologue but was rather the supreme pragmatist. As Ambassador Satish Chandra said in a paper published by the Vivekananda International Foundation, “he could easily accommodate the imperative for a better relationship with the United States with the requirement of a modus vivendi with China.” Chandra added that India’s progress in revamping its relationship with the US and China under the Vajpayee regime, even after nuclear tests that displeased both, is testament to Mishra’s diplomatic skill. According to the ambassador, the three areas where the officer left an “indelible imprint” were India’s nuclear policy, security systems and foreign policy.

After retiring from Vajpayee’s PMO, Mishra was consulted by the next Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh and his team, especially regarding the nuclear deal with the US. Contrary to the stand taken by the BJP, Mishra expressed his support for the India-US nuclear deal, which shows that he could rise above partisan considerations when it came to national interest. It was widely acknowledged that the massive improvement in India-US relations from the turn of century was due to his candid discussions with US interlocutors. Mishra emphasised that ties between the two countries could not reach their full potential without cooperation on critical issues such as high technology trade, civilian nuclear energy cooperation, and civilian space collaboration. To its credit, the US recognised the validity of this argument and sought to rectify the situation.

Two PMOs

The Accidental Prime Minister by Sanjaya Baru and AS Dulat’s A Life in the Shadows give us good insights into the 10 years of Singh’s premiership. Due to the coalitional nature of government, the PMO lost much of its sheen, partly because of the perception that the real power rested with then Congress president Sonia Gandhi. The principal secretary at the time, TKA Nair from the Punjab cadre, was no match for LK Jha, PN Haksar, PC Alexander, AN Verma, or Brajesh Mishra. Despite holding the longest tenure of seven years and 128 days, he did not exercise even a fraction of authority wielded by his predecessors. Pulok Chatterji, who succeeded Nair, did a shade better – for he was Sonia Gandhi’s appointee and his main loyalty was to her rather than his nominal boss. It was clear who was calling the shots. As a wag commented: the accidental prime minister had an ‘incidental PMO’.

Comparing Vajpayee’s and Singh’s PMO, Dulat, former secretary of Research and Analysis Wing (RA&W) and a functionary in the PMO, wrote that while Vajpayee’s PMO was a happy one, Singh’s was “a very tense, stressed out PMO … there always seemed to be a lot of wrestling going on within”. The Cabinet Secretariat, National Advisory Council, National Security Agency, and the Planning Commission emerged as strong contenders in the policy and advisory space.

All this changed with Narendra Modi taking over Raisina Hill in 2014. Phonetically speaking, this was the return of the Mishra era—for no other surname has seen this kind of a run.

Agricultural economist as principal secretary

Former Principal Secretary Nripendra Mishra, who currently heads the Shri Ram Janmabhoomi Teerth Kshetra Trust as well as the Prime Ministers’ Museum and Library Society (previously known as the Nehru Museum and Library Society) had been an exceptional bureaucrat. He had previously worked with two CMs of Uttar Pradesh— Mulayam Singh Yadav and Kalyan Singh—who were ideologically poles apart, yet recognised Mishra’s professionalism.

He was succeeded by PK Mishra from the Gujarat cadre. This author had the privilege of working with him in two capacities: as an agriculture secretary of West Bengal when he was the Agriculture Secretary of India, and as the director of LBSNAA during two Aarambh (combined civil services foundation course) training programmes organised on the birth anniversary of Sardar Patel, during which Prime Minister Modi delivered the keynotes.

However, it is important to place on record that if PK Mishra was not in the PMO, he would have made his mark as an agricultural economist. His PhD thesis at Sussex University was on Agricultural Risk Insurance and Income, published in 1996. He has also edited a book on agricultural insurance for the Tokyo-based Asian Productivity Organization, and a series on the subject in the Economic and Political Weekly. The current Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana is a direct outcome of his research.

Sanjeev Chopra is a former IAS officer and Festival Director of Valley of Words. Until recently, he was Director, Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration. He tweets @ChopraSanjeev. Views are personal.

This article is part of a series on the PMO.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)